MAJ : 6 décembre 2023

"Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence."

Introduction

The title, "Angkor Wat string orchestras", is more a wink than an evocation of a tangible reality. Indeed, it took us twenty years to find two representations of stringed instruments hidden among the thousands of medallions adorning the temple door jambs. Our research focused on the iconographic representation of harps in Angkorian temples. While Bayon and Banteay Chhmar provided us with a number of harps with relative ease, Angkor Wat gave us cause for (dis)hope for a long time, as the large bas-reliefs offer no instances of a cordophone. Most musical instruments and sound tools are in the hands of the military, Brahmins and rishis. In desperation, we had to explore again and again the medallion tapestries that adorn the jambs and some of the walls with different approaches and looks.

Angkor Wat, built at the beginning of the 12th century, represents the missing link between the very rare 7th-century depictions of cordophones at Sambor Prei Kuk and the very numerous ones at Bayon and Banteay Chhmar. To date (April 2022), the only cordophones represented in Angkor Wat iconography date from the early 12th century (this clarification is necessary as the iconography of part of the north gallery dates from the 16th century) and are two harps and a double-resonator monochord zither. While one (or two) lutes are mentioned in 9th-century epigraphy, this type of instrument is absent from all Angkorian iconography. Angkor Wat's iconography is scarcely more extensive, offering only four string ensembles:

- A Shiva dance in the west gallery, where two cordophones are visible;

- A Shiva dance in a staircase leading to the central terrace, in which the musicians are depicted, but the instruments are only hinted at;

- Two dance scenes in the south and north galleries, in which, once again, the instruments are only hinted at.

While the musicians are perceptible in their own right, there remains the delicate question of identifying the instruments, since they are not represented.

We know from our research that there are a finite number of instruments making up Angkorian string orchestras. Those represented at Bayon and Banteay Chhmar, nearly a century after Angkor Wat, offer us some clarification, but not exhaustiveness: we believe that some instruments are missing (drums, lute?) while others were duplicated, such as the monochord zither and the harp. Also, when musicians are depicted without their instruments, how can we identify their nature? What clues do we have to attempt a scientific approach? While some musicians are clearly depicted from the front, others seem to be seen from behind. This was a clever way for sculptors to avoid depicting details, limiting their efforts to the contours of the figures. Perhaps it was also a way of saving time, since everyone, immersed in their own culture, could recognize any musician at a glance. In the Angkorian period, musical instruments are depicted with very little detail, compared to their Indian origins. Musicians and singers are carefully positioned. This is undoubtedly the avenue to be explored. But we also know that the typology of male and female seating was (and remains) standard according to social rank. The Buddha, the king, the Brahmins and the common people are depicted with differentiated sitting positions.

In this article, we won't go back over the Shiva dance in the west gallery, where a harp and a zither are visible. You can access the article directly by clicking here.

Celestial dancer and musicians. Third enclosure, south gallery

This scene is centered around a dancer who, by the position of her legs, appears to be an apsara rather than a sacred dancer. The musicians could then be celestial gandharva musicians. This hypothesis is reinforced by the presence of dancing animals in the upper part of the image and warriors doing the same with white weapons below.

We know from the history of art that the visual artists of ancient societies often depicted the musical instruments of their environment, instead of those of the past, of which they knew nothing. So, although the figures in this scene are celestial musicians, and their origins date back to Vedic times, the instruments depicted are those of the Angkor Wat era. That's why we're working on the paradigm that the instruments hidden here by the bodies are those already known from earlier periods - Ishanapura, the archaeological site of Sambor Prei Kuk and Hariharalaya, the temples of the Roluos group - and later ones (the Bayon period).

The musicians' position

As a first step, we're publishing an image of the ten characters, cropped and enlarged. All are shown from the front.

For the image below, we propose a provisional hypothesis for the distribution of instruments, with a greater risk of error for the two red figures. We have used the instruments reconstructed by Sounds of Angkor, for illustrative purposes only. We are sorely lacking in occurrences to support our thesis during the Angkor Wat period, but we hope that this first option will provide an opportunity for criticism and counter-proposals.

Below, we publish the characters individually in their original version, then cut to size and, where appropriate, with instrumental simulation under the same conditions as above.

Female dancer

The apsara dancer is the central figure on stage, wearing a crown or diadem with four visible points. Nine musicians and singers look on.

Dance was a major art form in the Angkorian world. In the visual arts of the same period, dance does not necessarily require the representation of musicians. When it does, a pair of cymbals or a flute may suffice. We believe that in the minds of the ancient Khmer, dance implied music, so why represent it? A musician with his instrument is a static, non-sounding "object", whereas a dancer is a dynamic "object" executing a movement or sequence of movements. Moreover, given the constraints of sculptural surfaces and the difficulty of accurately depicting musical instruments - a problem that has never been solved to this day - a standardized representation of dance was enough to satisfy the ancient Khmers.

Zither player 1

This musician is in the typical position of a monochord zither player, with the right hand at the bottom of the instrument to pluck the string, and the left, higher up, to modify the pitch of the note by pressing on the string. A clue, if ever there was one, is the graphic element extending from his left shoulder, a sort of lotus stem terminating in a button. We don't understand what it does, or why it's connected to the musician. But perhaps there's nothing to it. Or does it mark the status of "first zither player", since the second zither player lacks one?

Zither player 2

This musician is in the same position as the previous one. The fact that zither players 1 and 2 are depicted one above the other could give credence to the fact that they are the same instrument with a first and second zithers, as was the case in the Bayon period.

Harpist 1

Harpists 1 and 2 are the only ones to have their arms outstretched, especially the left arm, which normally plays the lower strings. This position is generally that of the singers. Located just in front of the zithers, the two harpists have a normal place in the orchestral hierarchy. The left hand is extended by a large lotus flower surmounted by a stem ending in a bird's beak. Perhaps this is an artistic gesture that simultaneously shows the animal's neck and the harp's neck? The two harps depicted at Angkor Wat end in a bird's head.

Harpist 2

This second harpist also has his left arm outstretched. His hand ends in a lotus flower, but of lesser importance. Perhaps this is a way of marking the fact that this is the second harpist?

Drummer

The position of this musician is special. His right hand is raised as if to show the dynamics of the playing. Just above the flat of this hand, a line seems to mark the surface of a drum. Furthermore, the right knee has a slight offset which does not exist in other musicians, perhaps the end of the drum. We make two organological hypotheses here:

- an hourglass drum with tension variation (thimila). The right arm crushes the links which unite the two membranes to change the pitch on its. This technique is known in all thimila drum performances, but it is usually the left hand that performs this function and not the arm.

- a goblet drum for which the position of the musician is compatible.

Note that drums are never represented in the string orchestras of the Bayon period. However, this observation does not exclude the certainty of their real presence.

Scraper player

The scraper is almost always present in orchestras from the Bayon era. If it were a flutist, the hands would be positioned differently.

Singer 1

We know that at least one singer is necessary in this type of orchestra. He seems to be under the dancer. The clue is that his mouth is open. However, his arm is not straight, which is generally a criterion.

Singer 2

During the Bayon era, a second singer was often present in the most complete string orchestras, that is to say those where the zither and the harp were duplicated. However, this second singer plays the cymbals, or the scraper as in a single occurrence in Banteay Chhmar which is an option that we did not choose since there is already a cymbalist. However, it could be a scraper player or a flautist playing a terminal mouthpiece flute.

Cymbalist

Cymbals are the essential instrument for any string orchestra. We identified this character as a potential cymbalist by the position of his hands and a detail of the sculpture.

Prince Ream and his musicians. Third enclosure, north gallery

This scene depicts Prince Ream, hero of the Reamker (Khmer version of the Indian Râmâyana of Valmiki) and probably Princess Seda, his wife, who stands behind him. They are surrounded by a singer, musicians and monkeys from Hanuman's army. If the presence of Seda is attested, it could be a party organized after the release of the Princess from the clutches of the ogre Reap (Ravana), king of Lanka.

In the image below we highlight the princely couple, the singer and the musicians. The musical instruments are not represented, but we rely on a few meager clues to put forward a hypothesis.

Ream and Seda

Prince Ream with his bow and Princess Seda, his wife. If the prince wears a necklace, the princess wears no jewelry.

Female singer

This female singer wears her hair in a bun. Her right hand is outstretched, a tangible sign of verbal or sung communication in the Angkorian era.

Cymbalist

Any string or military orchestra (trumpets, conchs and drums) has a pair of cymbals, small or large respectively. In this scene, as in that of the south gallery described above, the outline of the jingles is present in the sculpture.

Harpists 1 & 2

As a hypothesis, these two musicians are harpists. The clue is the instrument's foot, which appears between the musicians' knees. The harp is held da gamba, i.e. on the thighs. We admit that this clue is weak, but there is no other. This harp foot is visible on the harp in the Shiva dance at Angkor Wat, as well as on those at Bayon and Banteay Chhmar. In contrast to the scene in the south gallery, however, the arm playing the lower strings is not extended. An oddity we'll have to come to terms with for the time being.

Zither players 1 & 2

Once again, as a hypothesis, these two musicians are zither players. The clue consists of the top of the neck of the instrument which appears above each shoulder, the musicians being seen from behind. The position of the two right arms is completely compatible with playing the zither. As for the right arm of zither player 2, it is folded into a position that is also compatible. The left arm of zither player 1, however, is invisible.

Apsaras, celestial dancers and musicians. Central staircase

This scene shows apsaras (upper medallions), musicians and listeners (central medallions) and celestial dancers (lower medallions). Its interpretation is tricky, as few details are visible, inaccuracies in the engraving cast doubt on the artist's/craftsman's true intention, and some parts appear unfinished.

The following is an enlarged, original, cropped detail of the figures in the central line. The first three from the left face to the right, the last two to the left. This line is centered around the central figure.

We now present the characters in order of probability of identification.

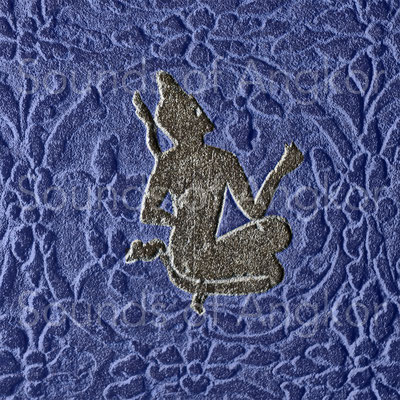

Main character: Ream?

The nature of this character is uncertain, but it could be Ream, the main figure who names the Reamker. What we've colored in red could be his bow, an attribute that rarely leaves his side. His outstretched arm seems to indicate that he is speaking.

Fourth character : ?

The fourth figure is neat. He stands in front of Ream. Clothing details appear and his pectoral muscles are highlighted. However, there is an error in the engraving: his right arm passes in front of his chest, whereas it is cut by the drawing line of the trunk. This error, combined with the inaccuracy of the second figure, means that this scene must be analyzed with caution. For the moment, we don't know what it is. Or is it a cymbalist?

First character: Hanuman?

The figure in the first medallion is a monkey. He is recognizable by his face and tail. It is a humanized figure, given its sitting and listening position. It could be Hanuman, the white monkey who led the monkey army to rescue Princess Seda from the clutches of Reap, the king of Lanka. This clue lends credence to the thesis that Ream is the central character.

Fifth character: zither player?

The fifth figure appears to be a musician, even a zither player. The top of the neck of his instrument is visible above his right shoulder, and we can even see what we identify as the resonator on his neck. Normally, the resonator rests on the chest, but the sculptor may have wished to offer this additional clue to identification. It's worth noting that on certain representations of zither players from the Bayon period, the resonator is sometimes depicted in this way. There is, however, one troubling point: the musician's right hand passes in front of his bust. It's in the right place to play. The left hand, on the other hand, seems to pass behind his hips. But perhaps this is just an inaccuracy in the sculpture...

Second character: ?

For the second figure, it is difficult to make a reliable assumption. In view of what we described in the scene of "Prince Ream and his musicians" above, the element protruding from the shoulder suggests a zither player. But here, nothing is less certain. The protruding object is larger and slightly bulging. Moreover, the position of the hands is not entirely appropriate. No clothing is shown. So, for the moment, we can't make any definite statements. This figure seems unfinished.

In conclusion

In this scene, a single character plays a stringed instrument, a zither. We know from Lolei epigraphy that the single-stringed zither was the main instrument of the orchestra, before the harp. So the sculptor may have chosen to minimize the importance of music by depicting only this instrument, which would be a first. Or perhaps the fourth figure is the cymbal player?

The enigma of the absence of cordophones at Angkor Wat

All this research and commentary leads to the question: why are string instruments and orchestras never represented at Angkor Wat?

King Suryavarman II and his architects chose to represent the epics of the Reamker and the Mahābhārata, as well as various Hindu myths, both on the walls of the third enclosure, on the pediments and in the stone tapestries on the door jambs. Martial instruments (trumpets, conches, drums and cymbals) abound. But he also had courtly scenes depicted in the south gallery, above the underworld scene. In Angkorian times, dance was paramount, and there was no dance without music played by cordophones. We consider, perhaps against the current, but with arguments, that the 1827 so-called devatas (according to the count of an American study) adorning Angkor Wat, are not (or not only) "goddesses" but women from the sovereign's direct environment (queens, princesses, concubines, musicians, dancers, etc.). Many of them carry lotus flowers, mirrors, jewels, palm-leaf books and the trappings of power... but never a musical instrument.Some positions do suggest instrumental playing, but the evidence is too weak, given our current state of knowledge, to build a theory.However... A correlation made by ourselves in January 2021 between a female scraper-singer with a looped bun from Banteay Chhmar and certain "devatas" wearing a similar bun in various temples from the Bayon period, leads us to believe that the correlation is solid.

It seems that the tapestries of historiated medallions were, for a certain number of them, sculpted or at least elaborated by religious men - former hermits / ascetics (rishi)? - who were familiar with Hindu sacred texts and legends. In addition, many images and series of narrative images feature ascetics and hermits. Sculptors knew perfectly well how to depict the rituals practiced among them in the forest, animals, hunting scenes and so on. Some very intimate scenes (which we are not in a position to publish), demonstrate the level of knowledge of life in the forest. When it comes to depicting a bell tree and the rituals in which they were used, notably funerary, all the ingredients are perfectly represented. Similarly, in the shadow theater scene in Angkor Wat's south gallery, the flute has been clearly represented, as this simple instrument, typical of forest and agrarian environments, was well known to the artists. We believe that these sculptors had no access whatsoever to the sphere of the royal court, either from near or far, and that stringed instruments were unknown to them, apart from cymbals, small cousins of war cymbals that they had probably seen on military parades.

The only true occurrence of a cordophone is the "monochord zither and harp" pair accompanying the Dance of Shiva. In this case, it is clear that the artist (or at least the draughtsman) had access to the royal court, since he depicted the King. The level of detail on the harp (general shape, presence of the foot, the bird's head and the device for attaching the strings to the neck) leaves no doubt that the artist was perfectly familiar with the organological structure of these instruments. On the same pedestal, lower down, the King is depicted on an elephant, recognizable by his conical crown, seat, parasols and fans.

This also raises the question of religious life at Angkor Wat during its construction. It should be remembered that Angkor Wat is more a mausoleum, that of King Suryavarman II (r. 1113-1150), than a temple proper. It would have been built over a period of 37 years, during which, apart from the rituals involved in the construction itself, there may have been little or no religious ceremony accompanied by dancing. The west entrance gallery, however, is full of representations of sacred dancers and dancing mistresses, but never of musicians, as is the case at Bayon. If ceremonies with sacred dancers had taken place in what could be considered dance spaces, like the great temples of Jayavarman VII, sculptors would have been able to carve stringed instruments (zither, harp or even lute). Perhaps there was a prohibition? If King Suryavarman II was truly a musician, then no one should stand in his way. The problem remains!

Musical Devatas?

India's Hindu temples feature numerous celestial figures, including musicians in high relief, whose precise function is illuminated by a musical instrument held in a playing position. In Khmer temples, these divinities are called "devatas". The great enigma of these full-length figures is that each one is different, without being attached to an identifiable celestial function. At Angkor Wat, for example, such figures with the same clothes, hairstyles, tiaras and jewels can be found in the historiated bas-reliefs in the third south gallery, west wing. There is little doubt then that these figures held a social and functional position in the royal court of Suryavarman II. PhalikaN's recent identification of the Jayarajadevi and Indradevi queens among the devatas of the Bayon period proves that there is a lost code of reading, yet to be rediscovered. In a similar vein to PhalikaN, we have identified what we believe to be female praise singers among the devatas of the Bayon period. See our article Female figures with curly bun(s).

Praise singer?

At Angkor Wat, one figure caught our attention because of its uniqueness. It's a devata depicted with her mouth open, whereas all the others have their mouths closed. Since her mouth is open, her teeth are showing. It is located in the west entrance gallery, on the interior side. Teeth are also visible on other devatas, but these are later wild modifications. This one is privileged in several respects: it is large, surrounded by rich floral decorations, the carving is very meticulous, the decoration of the dress is sumptuous, its legs appear transparent and, very importantly, it faces the central sanctuary. In the Bayon period, all the figures whose teeth are visible are singers, never female singers. During this period, male and female singers could be identified by several criteria:

- Singers: mouth open, teeth and/or tongue visible, hand or index finger outstretched.

- Female singers: bun with single or double curl, mouth open, hand or index finger outstretched. Sometimes the female singer simultaneously plays cymbals or a scraper.

In the case of the Angkor Wat devata we're interested in here, we've discovered a second clue: the index finger of her right hand is outstretched. We saw in previous chapters that, at Angkor Wat too, the outstretched hand shows that the figure is speaking or singing. We therefore believe that this is a singer, or more precisely, a singer of praises to the post-mortem deified king, given her position facing the central sanctuary, where the deceased king was laid to rest.

Devata Status

The bas-reliefs in the third southern gallery show female figures wearing various styles of chignon and tiaras. We can see that wearing a chignon or tiara marks a social status. To be more specific, all the women carried in a palanquin are wearing a tiara. This one therefore appears to be a high-ranking figure, all the more so as her tiara is adorned with six medallions arranged in a pyramid shape.

Female musicians?

If there is a female singer, could there also be female musicians and dancers in the group of devatas facing west? Unlike the singing, we have no other record at Angkor Wat on which to base our identification. We know from 9th-century epigraphy (Lolei, Bakong) that female dancers, singers and musicians were offered to serve the deities in the temples, a practice that was still common at the beginning of the 20th century at the Royal Court in Phnom Penh. Angkor Wat is probably both a temple and the mausoleum of King Suryavarman II. It seems that, like the Chinese emperors, he wished to depart for the other world accompanied by what was dearest to him: his court. So perhaps all these women known as devatas should be seen as dancers, singers, musicians, concubines and even, in the case of those surrounding the central sanctuary (bakan), his wives (queens?). But how to identify the function of each of them? Many researchers have attempted to answer this question, but there is no unanimous answer. We propose a working hypothesis for certain devatas in the same alignment as the open-mouthed "praise singer".

Above them, along their entire length, are what appear to be gandharvas riding mythical animals. According to the reference texts of ancient India, they are the celestial musicians. But they too have no musical instrument in their hands.Once again, they appear to be dancing, but the music is not represented.