Last update: December 5, 2023

Different kinds of musical ensembles serve real or mythical royal armies, parades, entertainment and religious rituals. Some are composed of percussion and wind instruments, other ones of string and percussion instruments.

Pre-Angkorian orchestras through iconography

Given the rarity of the pre-Angkorian iconography, it is impossible to draw any conclusions as to the nature of the instrumental associations. However, the data in our possession offer some acoustic coherence. We know three reliefs of the 7th century for which we have been able to identify the instruments despite of their condition. Given this rarity, we present here them all three.

Three lintels from Sambor Prei Kuk

The oldest orchestral representations are shown on three lintels dating back from the first quarter of the 7th century, from Sambor Prei Kuk, now exhibited at the National Museum of Cambodia. Musicians and dancers evolve under an arcade.

From L. to R.:

- Singer

- Flute. At the time of its discovery, the lower section of the flute was still in place, but has since disappeared

- Small cymbals

- Śiva dancing

- Hourglass drum with variable tension system: the left arm is clearly visible above the central depression of the drum. The broken right hand strike the skin as on the image of the following lintel.

- Arched harp.

From L. to R.:

- Singer (?)

- Monochord zither

- Small cymbals. Details are totally erased but the cymbals player of the lintel of Wat Ang Khna (below) allows this statement. Each cymbal is positioned vertically next to each other, whereas from the 11th century they will always be one above the other

- Śiva dancing

- Hourglass drum with variable tension system

- Character with indefinite role

- Arched harp.

- Singer and / or dancer (?): similar position to that of the first character on the left.

The lintel of Wat Ang Khna

The lintel of the Wat Ang Khna dates back to the second half of the 7th century. It represents the waving ceremony of a King. He is sitting at the center on a pedestal. He is surrounded by characters who converge towards him. At the ends, two groups of musicians are probably to be conceived as a single orchestra. The sculpture is summary. However, some instruments and dancers can be identified.

L: Flute, hourglass drum, cymbals, dancer, barrel drum.

R: Flute, barrel drum.

Angkorian string orchestras through iconography

String orchestras are depicted in Bayon, Banteay Chhmar and to a lesser extent in Banteay Samre, Preah Khan and Ta Prohm. We don't know if they played both at the temple and at the royal palace because the epigraphy is silent at this time. The iconography of Bayon clearly shows palatine orchestras composed of five sound entities; some of them are sometimes duplicated depending the place on the walls: one or two double-resonator zithers, one or two harps, one scraper, one pair of small cymbals, one or two male or male singers. At the palace, the string orchestras always animate the dance. If all the instruments are not completely represented, they are sometimes duplicated by some skillful techniques.

Palatine orchestra with instrumental duplication (center to right): singer recognizable by her bun and gestures, first zither, scraper, two harps, second zither, cymbals. Bayon, internal east gallery.

The sculptor represented four musicians and one female singer in the center recognizable by her bun and gestures. Only the harp and the zither are visible. The two characters in the background may be the cymbals and scraper players. Bayon, internal east gallery.

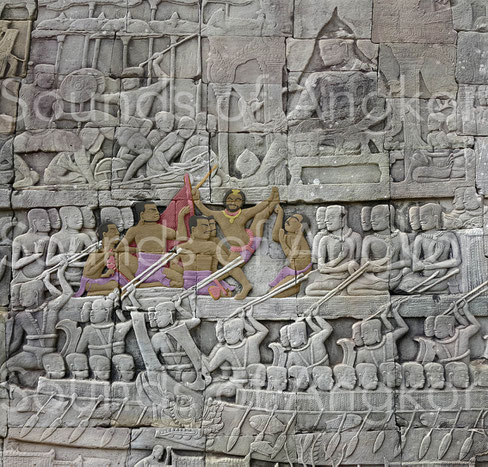

This low-quality bas-relief shows at the same time a palatine orchestra, two female dancers, the queens Indradevi and Jayarajadevi and King Jayavarman VII recognizable by its triconical crown, and auditors. He is curiously missing the singer. The character behind the harpist is probably the cymbal player, an indispensable instrument to any orchestra. Bayon, internal north gallery.

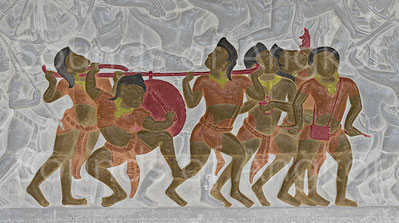

The orchestra of this bas-relief is atypical. The musicians are walking in procession in the midst of the crowd. What intrigues at first sight is the position of the heads of the two zither players and the scraper player. One must understand these musicians evolve in a crowd and that the acoustic power of each instrument is slight. That is why they turn to bring their ear closer to the sound source. We notice the mouth of the singer who projects the sound upwards, as if he wanted to be heard better from the crowd. Instruments from R. to L.: first double resonator zither, harp, (there is probably a second harpist behind this harp. We see a head but not the instrument), singer, second double resonator zither, scraper. Bayon. East external gallery. Late 12th - Early 13th centuries.

We are probably dealing here with a palatine orchestra reduced to its simplest expression given the very limited space available to the sculptor. Instruments from L. to R.: cymbals player (instrument not visible), harp, scraper, singer. East Bayon. Late 12th - Early 13th centuries.

This scene is the only one to represent an orchestra in Preah Khan of Angkor. It could be an offering ceremony made by a family. The sacred dancer at the center of the high-relief entertains the god or gods that this family honor. The musical ensemble consists of, from L. to R.: an arched harp, a stick zither with a double resonator, small cymbals and a singer recognizable by his stretched index finger. Late 12th - Early 13th centuries.

Instrumental duplication in 12th-13th centuries

As early as the 7th century, as we saw above on the lintel of Wat Ang Khna, some instruments were replicated (flute and barrel drum). From the 12th century, in Angkor Wat, some instruments such as the horns and the conchs are also. It is the same in Bayon and Banteay Chhmar for most of harps and zithers. Sometimes some characters with an indefinite role could be twice of the foreground. In the case of the harp, some reliefs show a second incomplete harp by various technical methods.

If duality or couple represents the basic nucleus, duplication of this duality is likely for certain instruments, notably martial instruments (trumpets, conchs, drums). The instrumental duality possesses, according to us and beyond the symbolic reasons justifying it, several acoustic and organizational aims:

- Acoustically, it doubles a minima the sound energy level; a minima means that even if the acoustic energy is only theoretically doubled, the induced phase shifts offer the sensation that more than two instruments play simultaneously thanks to harmonic enrichment.

- In the case of wind instruments, horns and conchs, the sound continuity is ensured by a tile playing: while one of the musicians breathes, the other one plays; then before the latter begins to breathe, the other starts to blow again. Let us note that the continuous breathing technique is also possible on these instruments. Contemporary ethnology testifies to this.

- The duo is the minimal formation to ensure the education of the musicians. The disciple follows the master in the learning of the repertoires, their interpretation, in the conduct of the suites of pieces to be interpreted. Moreover, if a string breaks, the musician can replace it without affecting the course of the ceremony. In this same spirit, the duet allows to ensure the musical continuity. Indeed, one of the two musicians can be temporarily absent without affecting the musical intention. It also allows the replacement of a musician under the same conditions. Indeed, if we refer to Cambodian ethnology, certain ceremonies sometimes last several days during which the musicians play without interruption, the musical pieces following one another without a single silence. Only an instrumental replication allows this continuity of sound. Jean Moura, in his book "Le royaume du Cambodge" (1883) reports the following: "In the large palace orchestras, especially on feast days, certain instruments are doubled and even tripled in order to produce more effect and also, no doubt, to allow the instrumentalists to take turns being absent without inconvenience, since the theatrical performances then last for days and nights on end."

These instrumental duplications are largely confirmed by the inscriptions from the beginning of the 9th century.

The special case of harps duplication

When the instruments play by pair, they are usually carved twice: cases of the horns, conchs in martial representations, zithers in the palatine and entertainment music. It is different for the harp because the instrument is large and encumbers the reliefs. Partial duplication uses three techniques:

- The neck of the second harp appears in an outline parallel to that of the foreground. All or part of the face of the second instrumentalist is represented in the background (1 to 3).

- The upper end of the neck and the face stand out in the background (4).

- Only the face stands out in the background (5).

Angkorian martial orchestras

The iconography of Angkor Wat, Bayon and to a lesser extent Banteay Chhmar is rich in martial instruments. Khmer people are predominantly represented, but there are also Cham, Thai and Chinese.

A strategy of communication

The acoustic vocation of the military instrument is to invade space as widely as possible. If war is won by weapons and tactics, the psychological and magical impact of sound is proven, both among Hindus and animists. To do this one uses powerful instruments capable of saturating the space, from the biggest drums to the horns and cymbals the most acute. Depending on the environment - plains, hills, mountains, forests - some instruments have more reach than others. The musical intention is not necessarily melodic, nor harmonic but rather timbral and, to a certain extent, rhythmic. We speak then of polytimbrality and certainly, in the case of the Khmer and Cham, of polyrhythmy in view of the diversity of the drums in action. The closest and best known example of this concept is still represented today by the Tibetan Buddhism orchestras. But what connection can there be between a warlike expedition and a Tibetan Buddhist ritual? Although preaching non-violence, Buddhism has "declared war" to the mental poisons as avidity, hatred and ignorance. The powerful instruments act on anything that could hinder practitioners' gait on the path of enlightenment: the enemy is identified, the weapons are deployed! The iconography of the 12th and 13th centuries shows drums, horns, conchs and cymbals. In the 16th century in the bas-reliefs of the north gallery of Angkor Wat are added oboes; it's the same in the present day Tibetan Buddhist orchestras. The rhythm generated by the drum ensemble probably had hypnotic virtues for the warriors. Epigraphy confirms iconography.

From R. to L. foreground: two dancers, large shoulder carried drum, small cylindrical drum struck with two sticks, hourglass drum.

From R. to L. background: cymbals (invisible but the player is present between the small trumpet player seen from the front and the former drum wearer), pair of small trumpets, pair of conchs, pair of large trumpets with a makara's mouth-shaped bell. Angkor Wat, south gallery, Historical Parade. 12th century.

King Suryavarman II parade orchestra, early 12th century

The two sequences below present on the one hand the martial parade orchestra of King Suryavarman II reconstructed by Sounds of Angkor and on the other hand, its staging in a 3D realization of Monash University (Sydney, Australia) with the collaboration of Sounds of Angkor for sound.

The instruments

The representation of instruments in the martial formations are stable between from 11th to 13th centuries. For the three temples mentioned above (Angkor Wat, Bayon, Banteay Chhmar) not all of them are represented for each group of communication, but there are always of same archetypes: large shoulder carried drum, cylindrical drums with various types of strikes, hourglass drums, goblet drums, trumpets, conchs, cymbals.

Sound organization

The instruments in the previous list could be divided into two groups: those with a fixed pitch (cymbals, goblet and cylindrical drum), those with variable pitch (hourglass drum, trumpet and conch depending the playing technique) and those that play loud sounds (large shoulder carried drum) and hight sounds (small horns, cymbals). These diversities and oppositions create the dynamics and the sound paste supposed to galvanize.

But how did the instruments interact with one another in a military context? To this question, several answers are possible: either chaotically or in a coordinated way with rhythms linked to tactical maneuvers. During our research through Asia, we have encountered both scenarios although the contexts of these epochs have disappeared. In the case of Tibetan Buddhism already mentioned, the intervention of the various instrumental groups (drums, cymbals, small and large trumpets, conchs, oboes) is very codified, the improvisation has no place. On the other hand, in a ritual procession commemorating the military exploits of Genie Giống in northern Vietnam, each instruments (drums, conchs, horns, gongs) play its part, the aim being to saturate the sound space rather than create overall coherence. Let us note however in this case a cultural loss related to the revolution. There is probably a notion of a sound overbid since, as can be seen on the bas-reliefs of Bayon in particular, when the Khmer army confronts that of the Cham, the musical formations are of similar nature. Thus, at the height of the battle, when the cries of the assailants mingled with those of the victims came to cover the orchestral chaos, the sound orders had to be drowned in the sound mass. Also, the more numerous and coordinated the musicians, the more effective military tactics were. Let us not forget that the beliefs of the time were based on a mixture of animism and Hinduism and / or Buddhism. Many of the soldiers enrolled in the armies were first of all animists. For the latter, sound communication with spiritual entities made sense. The sound has magical virtues like pieces of fabric crossing the body of the soldiers. If there was no magic of sound, why would we play in the temples to distract the divinities, why would we sing incantations and praises to the spiritual entities of the forest? Rites and social practices in no way differ from their religious equivalents.

Situations of representation

The musical martial formations are represented for various reasons:

- Commemoration of a battle in which the sovereign was taking part;

- Parade of appearance to the glory of the sovereign;

- Illustration of the Indian myths as Reamker and Mahābhārata.

Commemorations and parades are a form of propaganda to the glory of the sovereign, through which he affirms his status, his power, his splendour for the present and the future. Let us specify here the capacity of the ancient Khmer to project themselves in time. Indeed, some lapidary inscriptions temples foundations ask the sovereigns of the future to continue to maintain the buildings after their death.

Entertainment orchestras

In the ancient societies it is always delicate to separate the profane from the religious as the spiritual entities are omniscient and omnipresent in every everyday act. However, some scenes show musicians alongside acrobats, jugglers, wrestlers, thus offering here a certain formalism to this separation.

The juggler

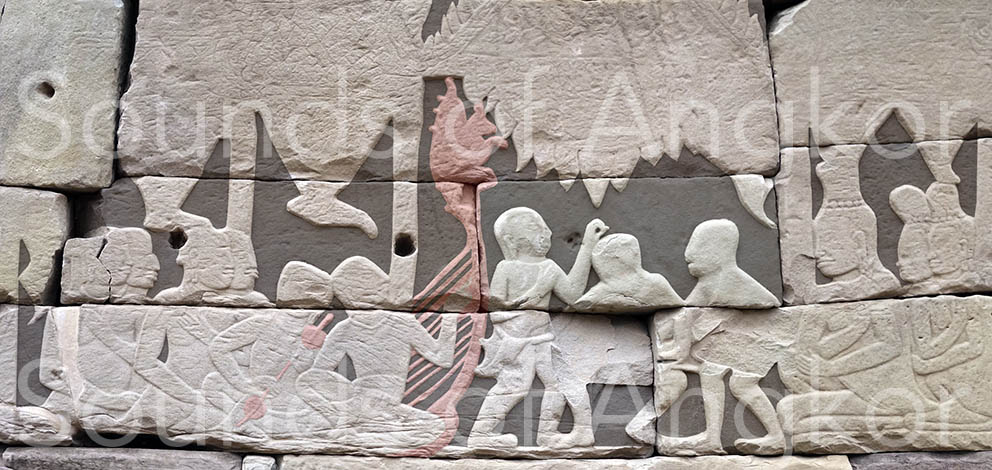

The scene below is from the Ta Prohm Kel chapel located to the west of Angkor Wat. It is the sanctuary of one of the hospitals of King Jayavarman VII. One finds a character juggling with balls accompanied, from left to right, by cymbals, a double resonator zither and an hourglass drum. If we compare this scene with the preceding one, of the same period, only the harp is absent.

The sword-swallower

The high relief shown here shows a knife-swallower accompanied by a woman striking a small barrel drum and another playing cymbals. The drum is held by a strap passing around the hips. These could be travelling artists such as they still exist in India and Nepal.

The acrobatic dancer

Some scenes from Bayon and Banteay Chhmar feature orchestras of similar structures animating dances that could be called acrobatic. Gathering and comparing all known iconography makes it possible both to confuse the realism of the situations, to analyse the structure of the orchestras and to supplement the iconographic data which are sometimes missing because of the degradation of the sculpture.

In Indian mythology, the dance poses presented in scenes 1 to 4 with a leg raised vertically and the opposite arm mounted above the head were called ūrdhvatāṇḍava (Sanskrit). They evoked the victory of Śiva in a dance competition with Kālī.

These bas-reliefs belong to the iconography of two temples originally Buddhist but partially completed and reworked in their iconography by the Hindus: Bayon and Banteay Chhmar. The significance of these dances is certainly different from that of the Indian origins if there was, in fact, a link. These four scenes show the same instrumental set arranged in a similar way, from left to right: a cymbal player (the instrument is not always visible but there is no doubt), a harpist, a zither player. On the scene 1, the harp is replicated. On 2nd one, the presence of a face in the background of the zither player may suggest the presence of a second zither. The four dancers wear a stick. A character, probably a singer, touches the leg or foot of the dancer, except scene 3. The dancers wear a bells belt, some a necklace of bells. The dancers 3 and 4 have as attribute, in addition to the stick, a ponytail attached to the belt. We also see, but unevenly, architectural elements - pillars, ceiling, hangings - and spectators. The harpist occupies a dominant position by its size among the musicians. He might be the leader. Given the degradation of the sculpture, it is not always possible to define the sex of the characters.

The scene 2 has comical anomalies. The cymbals player has two straight hands and shows his teeth, which is very unusual. As for the left arm of the harpist, instead of passing behind the harp, the normal mode of play, he passes in front, which seems to mean that he is also endowed with two right hands. Moreover, the number of strings of his instrument does not correspond to any tangible reality. As for the position of the zither player, seen from the back, it is inappropriate because his left arm should be at the top, and it is at the bottom. Still on the zither shown in profile, the lower part of the stick should be raised to hang the string, but it stops sharp. Obviously, all the musicians are smiling.

Two other scenes from the same two temples have similar orchestras. However, the dancers have different positions. On scene 5, the dancer has, as before, a ponytail and hooves in place of the hands. These two scenes are linked by the image of the horse as it's also the case for scenes 3 and 4. It is difficult to draw any conclusion as to the nature of these scenes, but it could be argued, as a hypothesis, that they would be dances of buffoon. A stele from the early 12th century refers to four terms describing the protagonists of these scenes: [rmmāṃ caṃryyāṅ smevya tūryya] dancers, singers, buffoon, musicians.

5. This bas-relief is very imperfect in its design. However, the sculptor seems to have wished to make appear two harps and two zithers. The colourization reveals, however, without certainty, these two imperceptible elements. One will notice the dancer's ponytail, his belt of bells and his anterior hooves. Bayon.

The orchestras of the north gallery of Angkor Wat

Part of the bas-reliefs of the northern gallery of Angkor dates from the 16th century except The Combat of Asura and Deva, in the west wing whose style and instruments are typically of the

original style of Angkor (12th century). The Asura and Deva Combat features classic martial musical instruments also found in Bayon and Banteay Chhmar. But

its quality is not as beautiful as the rest of the bas-reliefs of the temple.

As for the Krishna Victory on Asura Bāna, east wing (16th century), it presents new instruments and technical innovations compared to what existed in the 12th century

; on the other hand, its quality is mediocre. On certain scenes, instruments of any kind, without apparent coherence of association, are spread

before our eyes.

What are the new instruments and innovations in relation to the existing ones on 12th century?

- New instruments: arched gong chime, bossed gong, C-shaped. Note that the block flute probably existed before but that its representation is a first.

- Innovations on the existing: addition of supports to portable barrel drums and large shoulder carried ones.

Most of these instrumental archetypes survived in contemporary Cambodia. The only ones to have disappeared are the trumpets, with the exception of those made of buffalo horn.

Instruments from R. to L.: hourglass drum, pair of horns, barrel drum with integrated support, conch, gongs chime, pair of oboes, pair of bossed gong, large drum with support, cymbals, monochord zither with single resonator, three block flutes. Angkor Wat, north gallery, Krishna's victory over the Asura Bāna.

Martial orchestras are either reduced to their simplest expression, that is to say, an instrument of every kind (1), or widely deployed with duplication of each one (2, 3).

1. Instruments from L. to R.: cylindrical drum struck with two sticks, hourglass, trumpet, large shoulder carried drum, conch. This scene is one of the most beautiful achievements of the north gallery. Angkor Wat, Battle of Devas and Asuras, north gallery, west part.

2. Instruments from R. to L.: pair of shells, cymbals, pair of hourglass drums, pair of cylindrical drums struck with two sticks, cylindrical drum struck with hands, cylindrical drum struck with hand and stick, pair of large shoulder carried drums, pair of trumpets. Angkor Wat, Battle of Devas and Asuras, north gallery, west part.

3. Instruments from D. to L.: pair of large shoulder carried drums, trumpet 1, (drum partly concealed, perhaps a goblet one), pair of cylindrical drums struck with two sticks, cymbals, pair of hourglass drums, cylindrical drum struck with hands, trumpet 2, cylindrical drum struck with a bare hand and a stick, pair of conchs. Angkor Wat, Battle of Devas and Asuras, north gallery, west part.

Religious orchestras through epigraphy

The texts relating to musical instruments, singing and dance are composed of lapidary writings. We must distinguish texts of endowments as servants and objects to the temples, written in Old Khmer (7th-10th centuries.), and poetic texts, mostly praises, mentioning the names of musical instruments used for ritual or martial use composed in Sanskrit (pre-Angkorian and Angkorian eras). If the texts in the Old Khmer mention the names of the instruments, their precise use and orchestral combinations remain unknown. The nature of some instruments is still unknown to us, either because no direct iconographic source allows us to identify them (in the case of texts in Khmer), or because the names of the instruments mentioned already belonged to the past when they were engraved in stone (case of Sanskrit).

Music through Sanskrit texts

Musical practice is a sign of good education and subtlety of spirit through praise in Sanskrit of Indian origin. This inscription of Banteay Srei (10th century) reveals it*:

"He was the first in knowledge of the doctrines of Patañjali, Kaṇāda, Akṣapāda, Kapila, Buddha, medicine, music and astronomy. "

Or this royal praise of the Sdŏk Kăk Thoṃ stele (mid-11th century)**:

"Eminent in beauty, power, glory, science, virtue, actions, spiritual merit, he had no pride. He knew music; He had studied the arts: mechanics, astronomy, medicine, etc. "

"Experienced, learned, rich, renowned for his kindness to all and for his musical talent, he continually delighted the hearts of the courtiers by the five bonds of courtesy. "

* From French translation by Cœdès G. – IC I p.150-XX.

** From French translation by Cœdès G. & Dupont P. - BEFEO XLIII p.82 LXXII-LXXIII.

Religious orchestras in the early 7th century

We have inscriptions on the endowments of servants and materials of several temples. In order to stay within the framework of the subject that interests us, we will be interested in the women and men in charge of playing of musical instruments, singing and dance. We will rely mainly on the inscriptions published by George Cœdès, the works of Dominique Soutif and Saveros Pou, supplemented by a relation between epigraphy and Khmer or non-Khmer iconography.

An inscription from Angkor Borei (K. 600), dated Friday, January 21, 612 A.D., is one of the earliest pre-Angkorian writings referring to the sound. It is, however, only a list of servants with their function and name, but it gives us valuable testimony on the functional hierarchy of the dancers, singers and musicians in a temple. Moreover, the informative value of the names of the servants informs us of an essential feature of their artistic, moral or physical personality.

In 7th century the list announces first the total of the servants while in the 9th-10th centuries this information will be conclusive. At first, the lapicide lists the servants in this order: ramaṃ 7 dancers, caṃreṅ 11 singers, tmiṅ vīṇa kañjaṅ lāhv 4 harp players, zither, lute*. In a second step, it gives us the names of the servants with two omissions: the dancers should be seven but lists only six, then the order of presentation of the instrumentalists varies. What then is the right hierarchy? Our only knowledge of this subject is that in the 9th and 10th century the zither is always mentioned before the harp. Concerning the use name of the servants, we report here the translations given by Saveros Pou in her dictionary of Old Khmer-French-English of 2004 supplemented by his study "Music and Dance in Ancient Cambodia as Evidenced by Old Khmer Epigraphy".

* The name kañjaṅ was indeterminate before our research but now we know it is the zither because it is the only instrument both essential and absent. This name will not reappear in later inscriptions. Similarly, we translate lāhv, which will later be spelled lāv, by lute after having exhausted all other known possibilities.

jmaḥ ge raṃ/ Female dancers names

Carumatī/ Beautiful as a parrot

Priyasenā/ Beloved Servant

Aruṇamati / The colour of ruby

Madanapriyā/ A cheerful gaiety

Samarasenā/ (Who plays the role of) the soldier in the battle

Vasantamallikā/ Spring Jasmine

jmaḥ ge caṃreṅ/ Female singers names

Tanvangī/ Slim fit

Guṇadhārī/ With good qualities

Dayitavatī/ Who has a lover

Sārāṇgī/ Like an antelope

Payodharī/ Who has beautiful breasts

Ratimatī/ Delicious

Stanottarī/ With very developed breasts

Rativindu / Who has a mark of love

Manovatī/ Provided with spirit

Pit Añ/ Sanskrit name

Juṅ Poñ/ Sanskrit name

tmiṅ kañjaṅ / Female zither players names

Sakhipriyā/ ?

Madhurasenā / Who has the sweet voice

tmiṅ vīṇa / Female harp player name

Gandhinī / Scented

tmiṅ lāhv / Female lute player name

Vinayavatī / Disciplined

Two of the instruments on this list, the zither and the harp, corroborate those on the lintel of the 7th century in the National Museum of Cambodia (Ref. 1757), thus establishing a coherence between epigraphy and iconography.

The names of the female servants, though charming, do not tell us much about the qualities in relation to their function. On the other hand, one discovers that one zither player has a soft voice. Voice sung or spoken? Let us leave its part to the dream ... It is quite differently in the inscription of Kok Roka mentioned in the following chapter.

At the same time, in the 7th century., other inscriptions, like the latter, gave lists of servants, but didn't mention names of musical instruments. They are supplemented by functional terminology with lists of proper names: gandharvva, musicians, singers:

- Inscription of Sambor (Ta Kin - K. 129): 6 gandharvva (men), 9 musicians (vādya) and 18 female singers (caṃreṅ);

- Inscription of Lonvek (K. 137): 5 dancers (piṇḍa rapaṃ) and 12 singers (caṃmreṅ).

It is strange to note that on the inscription of Sambor no female dancer is mentioned.

Religious orchestras in the 7th-8th century

The Old Khmer inscription known as Kok Roka (K. 155), of uncertain provenance, is dated from the 7th or 8th century according to the style of its writing. Here again, it's a list of temple's servants.

Order of citation of the servants

- gandharvva / Musicians

- pedānātaka rpam / Dancers (first citation)

- caṃreṅ/ Singers (first citation)

- pedānāta rpam / Dancers (second citation)

- caṃreṅ/ Singers (second citation)

1. gandharvva / Musiciens

- vā Vaṅśigīta / Who sings while accompanying himself with a flute

- vā Kan-et / ?

- vā Karān / ?

- và Tpit / Very tight

- vā Kanren / Who grows, progresses

- vā Tvāṅ / Grandmother ?

- vā Aṃpek/ ?

- vā Kaṃdot / ?

- vā Kañcan / ?

Here, the name of the first musician informs us about a technique of singing accompanied by a flute. The musician could certainly play and sing alternately but it's not excluded that he could do both simultaneously. Such technique is known in India, especially in Rajasthan and Pakistan, where the flutist generates a throat drone while blowing in his flute (narh). The presence of the flute is rare enough to underline it. On the other hand, this name corroborates the existence of the flute in the 7th century, confirmed by the iconography.

2. pedānātaka rpam / Female dancers (first

citation)

- ku Raṅgaśrīya / The pearl of the theatrical troupe

- ku Mandalīlā / From a languid walk

- ku Caturikā / Intelligent, talented

- ku Amandanā / Active, awakened

- ku Suvṛttā / Beautiful appearance, which performs well

- ku Cāralīlā / With grace in the movements

- ku Tanumaddhyā / ?

- ku Harinākṣī / With gazelle's eyes

- ku Smitavatī / Smiling

All these female dancers whose name could be translated - actress dancers since the religious dances were probably narrative - has a name in direct relation to their function. It is also notable that the first name of this hierarchy means “The pearl of the theatrical troupe”.

3. caṃreṅ/ Female singers (first citation)

- ku Racitasvanā / Who performs melodious sounds

- ku Gāndhārasvanā / Who makes resonate the "Gāndhāra" sound (Sanskrit) that is to say the scale: Shadj (Sa), Rishabh (Re), Gandhar (Ga), Madhyam (Ma), Pancham (Pa), Dhaivat (Dha), Nishad (Ni)

- ku Raktasvanā / With passionate voice

- ku Suvivṛtā / That produces well articulated sounds

- ku Susaṛvṛtā / To the vocal cords well contracted

- ku Sārasikā / With the voice of the female heron

- ku Padminī / Lotus. Excellent woman.

All these female singers have a name in direct relation to their function with the exception of ku Padminī.

4. pedānātaka rpam / Female dancers (second citation)

- ku Haṅsavādi / With the voice of the wild goose haṅsa

- ku Sītākṣā / With the eyes of Sītā

- ku Vṛt(t)āvalī / Incurve line, in circle

Note that the first dancer has a name qualifying her voice. Would the dancers have also sung or is it an inversion with ku Padminī located just before in the text?

5. caṃreṅ / Female singers (second citation)

- ku Sugītā / Who sings well

- ku Suracitā / Well-dressed

- ku Kaṇṭhagītā / Who sings from the throat

- ku Muditā / Joy sympathizing joy

- ku Ka-oṅ / ?

- ku Kītakī / Panegyrist

The name of the second and fourth singers does not qualify their voice.

Religious orchestras, late 9th - early 10th centuries

The end of the 9th and beginning of the 10th century is rich in beautiful inscriptions from the major temples of this period: Preah Kô (879 AD), Lolei (late 9th century), Prasat Kravan (921 AD). These inscriptions list instruments without specifying the instruments playing together. Some names are identified with certainty, others doubtful, others still indeterminate.

Functional and spatial distribution of servants

The lists of servants assigned to the functioning of the temples are written both hierarchically and spatially in three dimensions, concentrically from the sanctuary, elevated in relation to the level of the natural soil, and extended to the most remote rice fields. The servants, especially dancers, singers and musicians, female and male, fit perfectly into this logic. The concentricity of the lists is in the image of the radiating power of the divinities and the sovereign, irradiating their energy in the four directions. The singers and the musicians generate at their level sound waves to the four cardinal points. These lists of servants again mention the function and name of each.

Lolei temple lists

The lists of each temple are singular. The Lolei temple supplies eight lists of servants, each linked to a week of the lunar calendar with alternating dark and light weeks. We will divide them into three groups as they appear in the inscriptions, separated by servants occupying other functions. The number of servants assigned to each function doesn't tell us whether they were operating simultaneously or whether they had substitutes. Similarly, we don't know whether the first group constituted a functional whole in its entirety. We will discuss, as a hypothesis, the physical arrangement of each group. We will split the first group (A & B) in two because we see a redundancy of singers, drummers and gandharva. In this group, only the praise singer is mentioned each week, the other servants are optional, coupled or independent.

First subgroup A, in the sanctuary

1 female inspector, only the clear weeks

3 female dancers

20 to 22 female singers

3 or 4 female players and male drum players

1 female cymbals player

0 to 2 gandharva, female or male

1 to 3 female zither player(s)

3 female harp players

1 to 3 female lāv player(s)

1 female chko (clappers?) player (clear week) or trisarī lute (dark week)

First subgroup B, in the sanctuary or in the immediate vicinity

1 to 2 female praise singer(s)

0 to 1 drum player, female or male

0 or 1 gandharva, female or male

Second group, in the enclosure of the temple, but outside the sanctuary

1 or 2 singer(s) - śikharā player(s)

1 or 2 gandharva, female or male

Third group, at the door

4 or 5 tūrya (trumpets) players

It is necessary to understand, through these various groups, independent ensembles operating in three communication spaces hierarchized from the center: communication beyond, here and there.

Communicate beyond: the dancers, singers and musicians of the first group are in charge of the relationship with the deities, their entertainment. The acoustic power of the instruments is coherent: the chordophones are acoustically reinforced by duplication to balance themselves in power with the many voices. In the end, no matter the sound power since this music is not made to be heard by human beings but gods.

Communicate here: The singers, śikharā players and gandharva of the second part would be assigned to the reception of the faithful, to their distraction and to that of the other temple servants. One can also assume, given their position with the various guardians, that they were working to keep them awake. The instruments are powerful enough to be heard at a few tens of meters. The voice of these seasoned singers adapts according to whether they officiate inside or outside.

Communicate there: tūrya players are assigned to communicate with villagers living outside the temple. The trumpets or horns are perfectly suited for outdoor use and can be heard to more than one kilometer on an open space and acoustically unpolluted at this times. Perhaps they sounded the hours of ceremonies, a task devolved in ancient India to conchs or powerful drums.

Among the servants there are two groups of gandharva: we shall call them gandharva of the interior and gandharva of the exterior. Without wanting to oppose the sacred to the profane, it's quite conceivable that the former had the function of singing sacred repertoires and the second ones, profane musics and songs to the attention of the faithful and servants.

In Cambodia, the Khmer musical ensemble officiating for arak ceremonies is perhaps, in the nature of the instruments, a survival of these religious practices. It is quite conceivable that there were musical ensembles dedicated to magic prophylaxis as there are still traces in South-East Asia in both the majority and minority ethnic groups.

In Vietnam, in a medium cult called hầu bóng, there are musical ensembles composed of one or two singers, a lute player, sometimes a flutist, a drummer and a bronze percussion player. The singers' role is to express the praises of the spirits who come to invest the body of the medium-dancer. They are paid by the spirits themselves through the hand of the latter. This remuneration is, one might say, proportional to the talent of the singer. If the repertoire is fixed, the way to accommodate poetry is free. Also, when the singer is skillful, he touches the spirits who show themselves in generous return.

In Nepal, under the pejorative appellation Gaine, more commonly known as Gandharva or Gandharba, we find bards who accompany their own songs by a fiddle, formerly a lute. They go from village to

village singing fixed or composed repertoires from facts of society. They are, in a sense, traditional journalists. They don't fail to sing praises to those who will listen to them in an attempt

to substantially increase the free donations made to them by the villagers.

These examples, even if they don't relate directly to the reality of the pre-Angkorian period, show that there is a direct relationship between the talent of the servants and a relational

effectiveness with both men and spiritual entities.

Another inscription, from Prasat Khnà (K. 356 / 980 AD), mentions two groups of musicians and specifies the details of their taking office:

"Reciters, string instruments (thmiñ) and percussion instruments players (thmaṅ), dancers, singers, cooks, sheet makers, bath water-warmers, take service once a day; (tūrrya) musicians — or trumpet players?, (gandharvva) singers, śikharā — string instrument player, (thmaṅ huduga) huduga drummers, take service three times a day. "

This text is interesting for more than one reason: the first part mentions the functions of the instrumentalists (thmiñ, thmaṅ) without specifying the exact nature of the instruments. In the second part, it is stated thmaṅ huduga, that is to say huduga drummer. Now for tūrrya - which we think are trumpet players - and śikharā, the function seems to be assimilated to the instrument. Unless the term śikharā is directly related to the gandharvva's function. In this case, the gandharvva śikharā well said would be a category of specialized singers-instrumentalists.

Symbolism of the divinities' female servants

As we can see in the first group of the Lolei list and those of other temples elsewhere, the presence of women is dominant. To acknowledge this, Sarasvatī, the music goddess, is a woman, and Tara, the first female goddess of Buddhism, plays harp in Java.

Through this brief statement, it is clear that it is important to leave the woman in charge of the communication with the divine.

Religious orchestras in the 12th century

Texts referring to worship music during the Angkor period are rare. The stele of Phnoṃ Sandak*, dated 1119-1120 AD, presents a short list unspecified:

"The venerable Lord Guru Śri Divākarapaṇḍita dug the piece of water called Śri Divākarataṭāka in the temple of K. J. Bhadreśvara, founded āśrama, placed slaves there, men and women. He offered the villages of Madhyamadeśa, Taṅkāl and the related clearing portions, as well as slaves, men and women ... He instituted a supplies service according to this list: husked rice, oil, sacred clothes, lamps, incense, necessary for the bath, [rmmāṃ caṃryyāṅ smevya tūryya] dancers, singers, buffoons, musicians, flower offerers for worship, daily. "

The authors here translate tūryya by musicians in the general sense. This term refers, at pre-Angkorian times, as we have already mentioned, to trumpet players but here, it must be noted that this term could encompass musicians in general (?).

* Cœdès G. & Dupont P. – K. 194 A - BEFEO XLIII p.143-144-42-48.

The celestial orchestra and the symbolism of the number five

If the Khmer architecture is structured around the number five - number of degrees and summit towers of the mountain temples including the five summits of Mount Meru described in the Hindu sacred texts - the celestial orchestra and some sound instruments respond to this same canon. The K. 294 inscription of the Bayon temple reveals an important phrase about the structural symbolism of the celestial orchestra: pañcāṅgikatūryya, translated by George Cœdès as "ritual orchestra of five musicians". It may be asked whether this translation reflects the initial spirit. There are, in India and Nepal, orchestral ensembles designated by the prefix derived from pañcā (five). The number five concerns only the nature of the instruments and not their duplication. Consider two cases only:

- In the south of India, in the Kerala state, the instrumental ritual called panchavadyam consists of five instruments including three drums -suddha-maddalam, edakka, timila- a pair of elathalam cymbals and a kombu trumpet;

- In Nepal, the traditional orchestra of the Damai is called pancai baja. It consists of five types of instruments, some of which are duplicated by pair: sahnai oboe, large damaha kettledrum, small tyamko kettledrum, dolakhi cylindrical drum and jhyali cymbals.

These examples demonstrate the importance of the symbolic number five in the structure of orchestral formations. Today, this symbolism is less important and it is not unusual to meet amputee orchestras of a part of their members. The structure of the Angkorian orchestras was probably organized around the number five but the lists of donations to the temples and the iconography don't let us glimpse because we don't know if instrumental duplication was taken into account or not. As for iconography, we are convinced that not all instruments are represented.

Martial orchestras through epigraphy

Martial orchestras in the 10th century

Texts relating to martial orchestras are written in Sanskrit, the poetry language. Also we have no references to know the names of the instruments for military use in ancient Khmer besides the śaṅkha conch, invariable term through time, passing from Sanskrit to Old Khmer and then to contemporary one.

One of the most eloquent inscriptions on martial orchestras is the K. 669 one. It comes from Prasat Komphus (973 AD). Another, K. 263 C, similar and of the same founder, comes from Wat Preah Einkosei (983 AD). These inscriptions have a poetic character borrowed from classical Indian literature and there is no evidence that the evoked instruments were known to the Khmer at the time of their writing. Moreover, the presence of stick zithers and transverse flutes alongside the powerful percussion seems anachronistic. This Sanskrit literature is the work of scholars with a knowledge of classical texts. Most of the cited instruments probably existed in the Khmer Empire, but under different names. Some terms still exist in the Sanskrit vocabulary of modern India (tāla, timila, ghaṇṭā, śaṅkha) but sometimes refer to different instruments (vīṇā = different kinds of zithers but not the harp).

George Cœdès proposes, in the Volume I of his Cambodian Inscriptions, a translation of which we are attempting here an organological revision. However, some names remain dubious or refer to vague instruments.

Original Sanskrit text

paṭupaṭahasumiśrair lāllarikaṅsatālaiḥ

karaditimilavīṇāveṇughaṇṭāmrdaṅgaiḥ

puravapaṇavabherikāhalānekaśaṅkhair

bhayam akṛta ripūṇāṃ yas sadā vādyasaṅghaiḥ

Original French translation by G. Cœdès

"Avec les bruyants tambours, auxquels se mêlent agréablement les sonores cymbales de cuivre, avec les karadi, les timila, les luths, les flûtes, les cloches et les tambourins, avec les purava, les timbales, les bheri, les kāhala et la multitude de conques, il inspirait continuellement la terreur aux ennemis par la multitude de ses instruments de musique."

English translation

"With the noisy drums, with the coarse cymbals of copper, with the karadi, the timila, the lutes, the flutes, the bells and the tambourines, the purava, the kettledrums, the bheri, the kāhala and the multitude of conchs, he continually inspired the enemy with terror by the multitude of his musical instruments."

Several musical instruments names appear

paṭupaṭahasumiśrair lāllarikaṅsatālaiḥ

karadi/timila/vīṇā/veṇu/ghaṇṭā/mṛdaṅga/iḥ

purava/paṇava/bheri/kāhalā/neka/śaṅkhair

bhayam akṛta ripū ṇāṃ yas sadā vādya/saṅghaiḥ

There is no iconography relating to this text in the Angkorian period. On the other hand, the north gallery of Angkor Wat shows a curious martial ensemble, also brilliant by its acoustic incoherence. In the enumeration of the inscription there are instruments, whose functional incompatibility is obvious: what can a vīṇā zither do acoustically speaking in the face of powerful war drums? The bas-relief inspires the same tought. But could we cross the inscription of the stele of Wat Prah Einkosei with this iconography? Would the designer of the bas-relief have been inspired by it? Let us mention beforehand that in the 16th century it's unlikely that anyone who knew how to read Sanskrit. On the other hand, the theory that a drawing dating from the 12th century would have served as a basis for the completion of the bas-reliefs in the 16th century, vanishes here with the presence of instruments that didn't exist during the reign of King Suryavarman II. At least part of these drawings have been modified. Despite his inconsistencies, let's try the experiment by taking up the list and facing the instruments of the bas-relief. The text mentions thirteen instrument names, the bas-relief shows eleven types (photo below).

Instruments from R. to L.: hourglass drum, pair of horns, barrel drum with integrated support, conch, gongs chime, pair of oboes, pair of bossed gong, large drum with support, cymbals, monochord zither with single resonator, three block flutes. Angkor Wat, north gallery, Krishna's victory over the Asura Bāna.

There are missing in the bas-relief from the original list, but instruments (unknown at the time of the original text) didn't exist (oboes, bossed gongs, gong chimes). We cannot draw any conclusions from this projection, only to ask the question of the coherence between the old text and the 16th century bas-relief.

Orchestras in the scenes of Reamker and Mahabharata in Angkor Wat

What credit to bring to the instrumental iconography in the bas-reliefs of the epics of the Reamker and the Mahābhārata in Angkor Wat regarding to the epigraphy? This problem of the discrepancy between the written and the graphical representation is a constant that also affected the Medieval Occident. To represent the instruments named in the texts of the Old Testament, illuminators or sculptors of the Middle Ages were inspired by those of their time. Thus, for example, the cordophone of King David became in turn harp or lyre, two instruments known in the Middle Ages. These instruments did exist at the time of the genesis of the Old Testament, but their form was unknown to medieval illuminators. We find the same problem among the ancient Khmer. Having no model, it was impossible for them to represent an instrument that had disappeared for centuries. Thus they carved those of their time, representations to which one can bring a just credit given the recurrence regained between the various temples.