The jesters of Angkor

Angkor Thom, the royal city, was erected during the reign of the Royal Triad Royal Triad who governed from the late 12th century until the early 13th century. At the heart of this city stands the Bayon, the state temple. Approximately 300 meters north of the latter, one discovers an imposing esplanade 400 meters long, called the "Terrace of the Elephants." This name comes from the multitude of sculptures representing pachyderms adorning the base walls of the former royal palace. About half a century after the death of Jayavarman VII, an unidentified king had a monumental ensemble of obscure symbolism erected, now known as the Northern stoop. There, one observes representations of multi-headed mythological animals, martial deities, as well as characters with abnormal physical characteristics, who would be considered artists today: musicians, singers, jesters, and dancers. This Northern stoop offers a singular perspective, specific to an ancient society, on the notion of "disability." It is not only envisioned from the angle of physical or intellectual deficiencies but also from that of abnormal mental faculties.

Texts, photos, videos © Patrick Kersalé 2011-2024, unless otherwise noted. Last updated: January 7, 2025.

Introduction

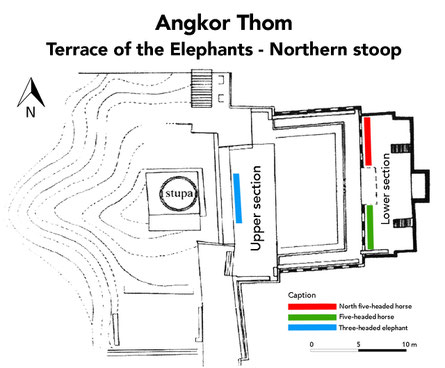

The present study aims to apprehend the singular nature of the characters represented on two distinct but stylistically and thematically analogous architectural ensembles: the upper part and the lower part of the "Northern stoop" located north of the Terrace of the Elephants. These elements were restored using the anastylosis* technique, which involves reassembling the original blocks, starting in April 1996, under the supervision of Jacques Dumarçay and Christophe Pottier, members of the French School of the Far East (École française d'Extrême-Orient - EFEO). They constitute unique specimens in the Khmer Empire.

Despite the conservation efforts deployed, numerous stones are missing from these ensembles, probably reused for other works. Nearby, archaeologists have carried out partial reassemblies of scattered stones.

The upper and lower parts are generally in a good state of conservation, having been preserved underground for several centuries. However, degradations have occurred since their reassembly, notably the theft of sculpted heads, the memory of which has been preserved thanks to photographs taken by the EFEO.

*Anastylosis: Restoration technique consisting of reassembling a building using its own original architectural elements.

Lower section ensemble

The entire lower part of the Northern stoop is notably complex. We will focus our study on the scenes depicting artist figures. This architectural portion presents two five-headed horses, one led by a Cham figure (South) and the other by a Khmer figure (North). These mythological animals, unique in Angkorian art, raise questions about the foundations of their presence in these places, perhaps linked to a Hindu or local legend.

These horses are surrounded by different representations:

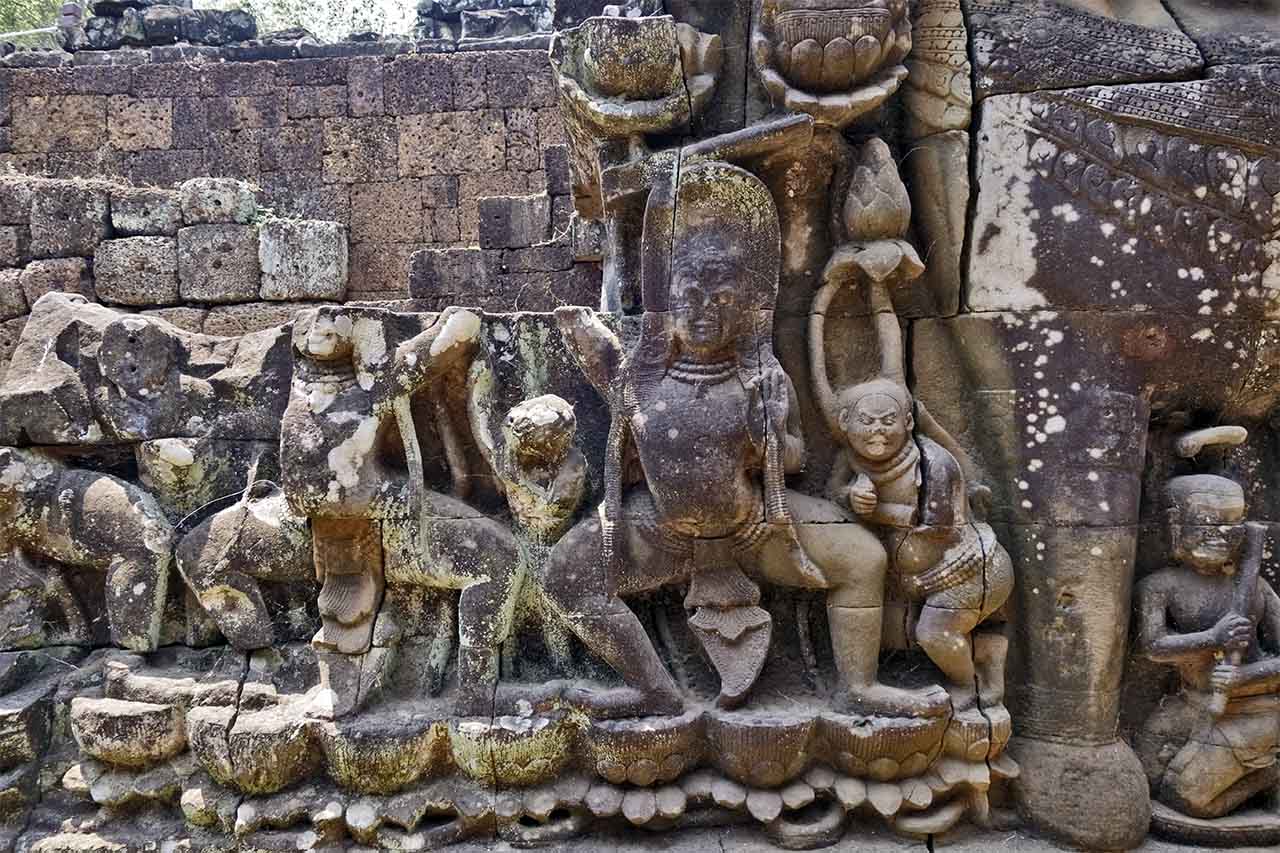

- Male deities resting on lotuses, armed with a staff and seeming to perform a martial dance. They could be naga kings (guardians of waters and earth), recognizable by their headdress and position between lotus stems.

- Sacred dancers adopting a stereotypical posture in line with the canons of previous centuries, one foot on a lotus, the other raised, adorned with an imposing diadem.

Figures with singular physical traits, integrated into the interstices of the composition. Although we use the Western notion of "artist" here, this terminology did not exist in the Angkorian era, where each person was designated by an appellation linked to their social rank and role.

Upper section ensemble

In the upper part of the northern stoop, figures similar to those in the lower part are displayed between two three-headed elephants whose trunks are immersed in lotus flowers, a stylistic detail that appeared during the reign of the Royal Triad. We also find male divinities adopting martial postures without staffs, as well as sacred dancers in codified positions displaying the standardized gestures typical of the preceding centuries.

Tableaux of scenes

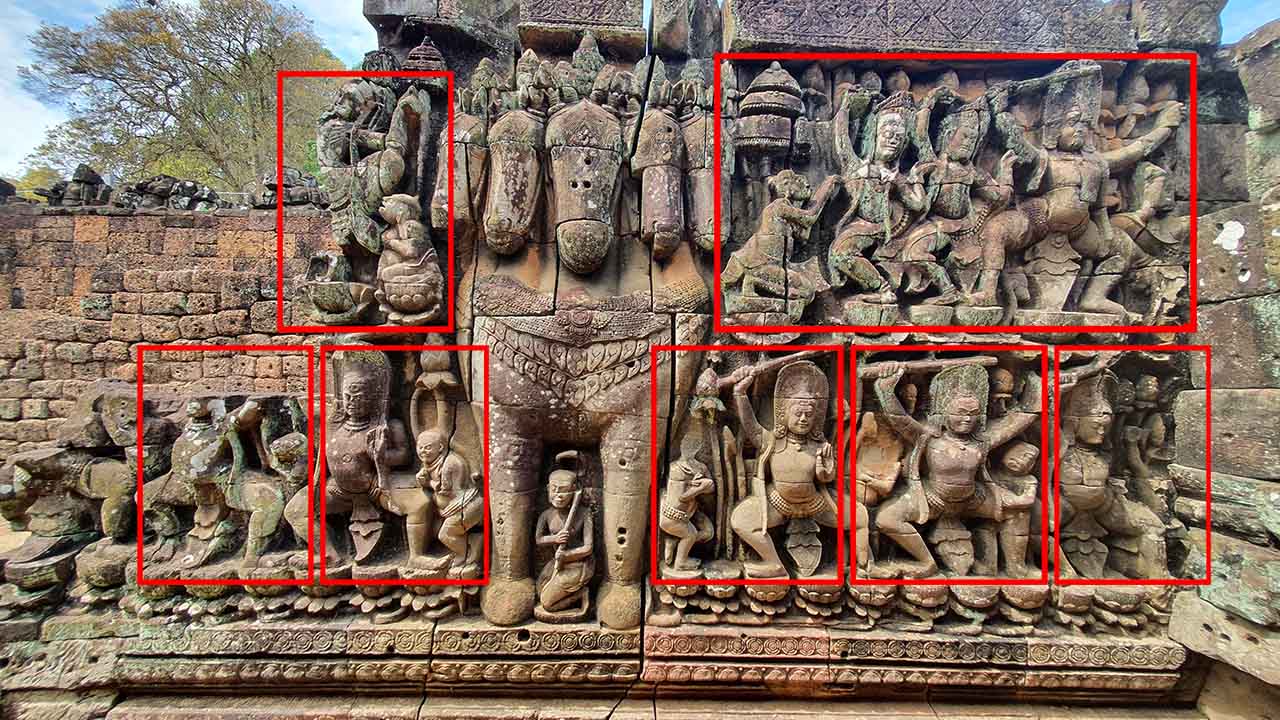

The characters we have just mentioned compose two immense tableaux, themselves subdivided into scenes associating one or more deities with one or more artists (delimited by the red rectangles on the photos). The sculpture, like Brahmanical ceremonies, creates a profusion, synonymous with beauty from the Brahmanical point of view.

In the ceremonies, several actions take place simultaneously for two essential reasons:

- The rituals are celebrated not for men but for the gods, able to hear the messages and see the offerings amidst the profusion.

- If all the rituals had to be performed sequentially and not simultaneously, the ceremonies would last too long. However, it is known that certain ancient rituals, such as that of the sacred fire, could extend over several years.

The protagonists

Mythological multi-headed animals

Mythological multi-headed animals are legion in Khmer art. The most common is the naga, a serpent with three to nine heads. Second in position is the three-headed elephant, the mount of the Hindu god Indra and of the Khmer Royal Triad. Finally, at the Northern stoop of the Terrace of the Elephants, there are two five-headed horses and two seven-headed horses (one of the two seven-headed horses was reassembled about a hundred meters from the Northern stoop). Like the multi-limbed deities such as Shiva, Vishnu or Krong Reap, the king of the giant ogres of Lanka, having more heads offers intellectual superiority over humans.

Divinities

The deities constitute the most prestigious characters and their aesthetic representation is particularly refined. Comparatively to the other protagonists, they are of great stature, sporting mustaches and a smile despite their martial attitude. Their headdresses and clothing are adorned with lotus flowers and phka chan (ផ្កាចាន់), a four-petaled flower omnipresent in the decoration of Khmer temples. They wear imposing necklaces of precious stones as well as belts of pearls (or bells?). They seem to delight in the praises of the singers and the buffooneries of the dwarves. Nothing seems to disturb their serenity.

Artists

Four categories of artists take part in the entertainment of the gods: singers, musicians, jesters and dancers. The first three perform in the gaps left by the gods. The female dancers, on the other hand, take pride of place.

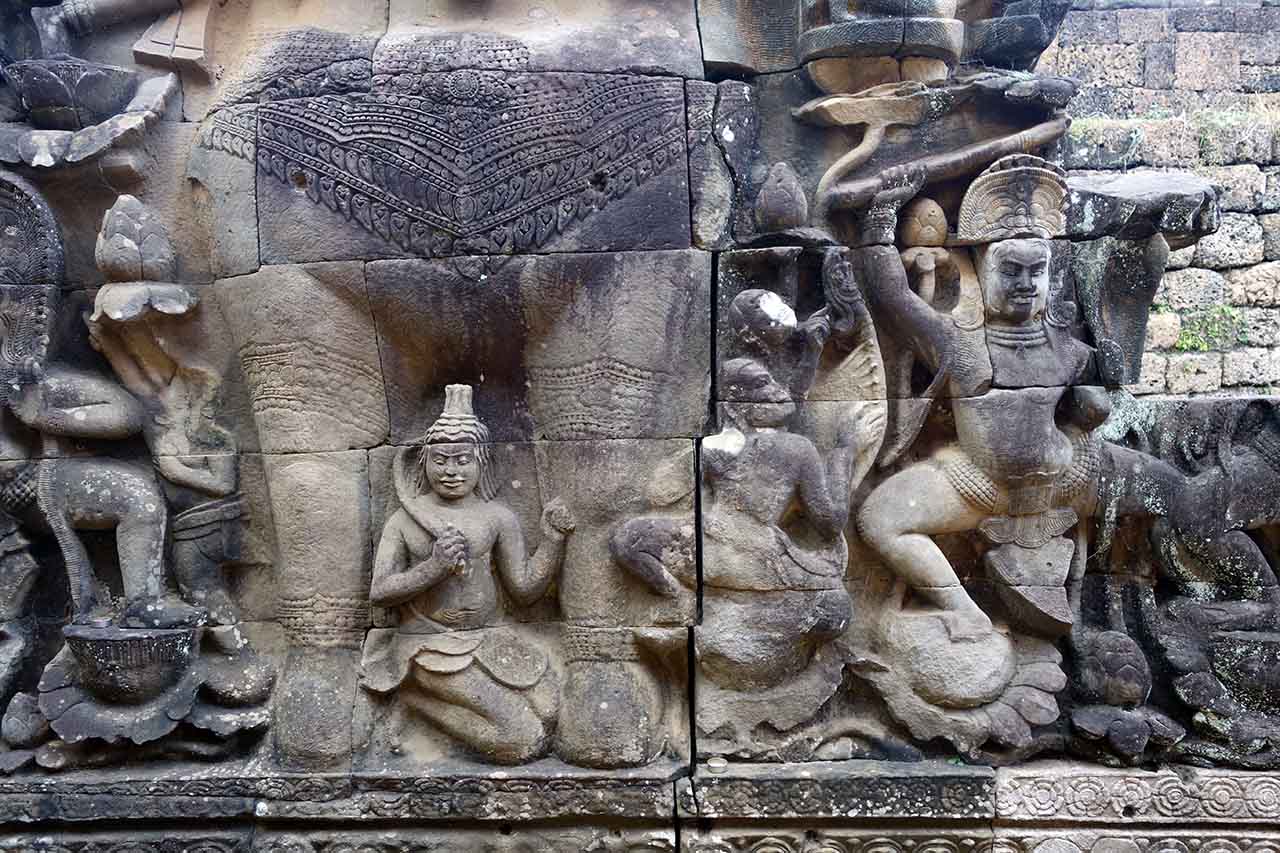

Singers

The singers are identifiable by their open mouth and/or their outstretched index finger or arm, a conventional sign of sung or spoken verbal communication. This stereotypical gesture is recurrent in Angkorian iconography since the Angkor Wat period. The typology of the singers' faces varies, as does their apparent age. In the photograph opposite, wrinkles furrow the cheeks and the top of the nose of the character; moreover, he sports a mustache, a beard surrounding the neck, and long pierced ears. His tongue is visible, but not his teeth.

Musicians

Musicians are associated with their instruments: there are two viṇā Garuda harp players and one chhing cymbal player. The Garuda-headed harp almost always signals the presence of a jester. Indeed, Garuda's head is never depicted on harps played in temples or at court.

Jesters

The jesters are characterized by various physical traits, attitudes and accessories: they are dwarves with small ears and thick continuous eyebrows, their hands crossed over their chests. They wear what appears to be a belt and a necklace of bells as well as a second necklace with a pendant, already visible in scenes of buffoonery at Bayon and Banteay Chhmar. Regarding the eyebrows, it could be a wig or a black line aimed at reinforcing the grotesque character of the figure. This artifice remains used in Cambodia and Southeast Asia by jesters performing on stage and on television.

The jesters' clothing may parody that of the deities, with their imposing belts and necklaces. But the parody does not stop there. Some of them have their legs crossed as if they were clumsily trying to dance; one of the jesters trips himself, falls forward and lands on the deity's knee. Another, his twin (?), is about to do the same, but his left foot has not yet reached his right ankle, unlike the previous one.

One of the twins (if ever there was one) had lost his head due to looting since the anastylosis reassembly. Thanks to an EFEO photograph and the magic of DTP, he was able to regain his head for the screen!

Female dancers

The sacred dancers present near the deities generally do not present any pathology. However, one of them adopts an uncommon attitude. In the totality of Angkorian sculpture, the facial expression of dancers remains relatively standardized: a smile or expressive neutrality. Here, she wears a broad smile revealing six teeth, namely the four incisors and the two canines. She wears five pearl necklaces adorned in their center with a lotus flower design and a sixth one below, adorned with a chan flower. In the center of her forehead, a lotus flower. Below her diadem, passing above her forehead, over her ears and descending on either side of her body, a jasmine garland. This representation of a dancer is parodied to the extreme.

Teeth are very rarely shown in Angkorian art, except to underline the wild character of characters from the Khmer point of view, or to demonstrate a grotesque character. At Angkor Wat (early 12th century), two devatas among the 1,827 that this temple counts show their teeth, without being able to understand the meaning, except that of singers with inappropriate language but accepted in the context of buffoonery.

If the even number of visible teeth when smiling is dictated by the nature of the dentition, it may not be a coincidence that they are thus exhibited. The singer, at the feet of this dancer, also reveals six teeth. It will be noted that the number of heads of the multi-headed animals is always odd. Among the Khmers, odd numbers are auspicious and even numbers inauspicious. Thus, the association between this singer and this dancer demonstrates the offbeat character of their presence and, by extension, the fact that the even number of teeth renders the content of their verbal or bodily discourse inconsequential.

Artists and their pathologies

After having briefly described these "celestial" artists with singular physiques, it is appropriate to examine a scientific analysis published in August 2007 in the magazine "Pour la Science" (p. 96-97), co-signed by P. Barbet, J.L. Fisher and C. Jacques, entitled "The Dwarves of Angkor". The authors describe, among the possible pathologies, cases of "achondroplasia — one of the most frequent forms of dwarfism accompanied by an exaggeration of the lumbar lordosis and characteristic anomalies of the skull and face (protrusion of the frontal bosses, truncated aspect of the back of the skull, flattening of the root of the nose)".

This achondroplasia would only concern the jesters themselves, and not the musicians or singers. Despite this flagrant abnormality, they seem intellectually both lively and mischievous. The corollary of this mental fulgurance is the physical handicap that accompanies it. The fascination for these abnormal characters is therefore twofold.

"We find these microcephalics particularly well sculpted and personalized in the high reliefs of the Terrace of the Elephants. In addition to these dwarfisms, certain sculptures of Angkor evoke the phenomenon of trisomy 21: a flat face with rounded and retained cheeks on the side, fine and oblique eyes, a small nose, thick lips and a voluminous rounded tongue". Finally, the authors mention an open mouth as a characteristic of the pathology. Certainly, even if this observation is correct, the characters with an open mouth are singers perfectly recognizable by their outstretched hand or index finger, a Khmer norm widespread from the Angkor Wat period; unless one is a ventriloquist, there is no better technique for singing than opening one's mouth...

The physical characteristics of jesters differ from those of singers and musicians.

Temple servants through epigraphy

While dancers, singers and musicians are widely mentioned in Angkorian epigraphy, jesters appear only more rarely: the stelae of Sdŏk Kǎk Thom, Phnom Sandak (K. 194) and Práh Viḥār (12th century) — Georges Cœdès, Pierre Dupont (1943). They are referred to as smevya, a conjectural translation based on a connection with the Sanskrit term smetavya, lit. risible (1943:148). In the pre-Angkorian Khmer inscription K. 78, they are called bhanda. In modern Khmer they are called neak kampleng (អ្នកកំប្លែង), lit. "comedy man".

- K. 194, stanzas 42-44. "He instituted a service of supplies according to this list: husked rice, oil, sacred cloths, candles, incense, ablution necessities, dancers, singers, jesters, musicians, flower vases for worship, daily."

- K. 194, stanzas 45-48. "At K. J. Çrī Çikharīçvara, the venerable lord Guru Çrī Divākarapaṇḍita erected the Dancing Lord, a golden image [of the dancing Çiva] for the deceased queen (kanlon kamraten an). He offered goods the villages of ... (Çambhu)grāma, Bhavagrāma; he dug water reservoirs in all the villages … , founded an āçrama, placed male and female slaves, offered goods and instituted a service of supplies, according to this list: husked rice, oil, sacred cloths, candles, incense, ablution necessities, dancers, singers, jesters, musicians, flower vases for worship, daily." (1943: 148).

- K. 194, stanzas 7-10. "At K. J. Çivapura Danden ... (he gave) the villages of Caraṅ, Tvaṅ Jeṅ, Khcoṃ, dug a water reservoir, founded an āçrama, placed complete male and female slaves, and offered all sorts of goods. The daily supplies are: dancers, singers, jesters, musicians, husked rice, oil, sacred cloths, candles, incense, ablution necessities, four (sorts of) oil, flowers for worship, flower vases. The goods offered are: golden bowls, rings, jewels, footed cups, cups, ewers, spittoons, elephants, horses, standards, white parasols, tiered parasols, dlaḥ spittoons, pitchers, dlaḥ basins, jars, trays, hangings, and innumerable cloths. He covered the towers, courtyards and causeways with cloths." (1943: 149)

It should be noted the mention of gifts of jesters together with those of dancers and musicians. In these inscriptions, the men and women offered for temple service as dancers, musicians and jesters are considered supplies.

Nature of sound communication

In the context of the religious life of Brahmanical and Mahayanist Buddhist temples under the reign of the Royal Triad, singers, musicians, jesters and dancers had the function of communicating with the deities. With the exception of the jesters, all these servants officiated in the temples with the sole purpose of establishing a link with the gods:

- The singers, both men and women, through sacred texts and formal or improvised praises.

- The dancers expressed themselves through significant gestures involving all parts of their bodies.

- The musicians supported the singing and dancing with their art.

- As for the jesters, it is difficult to define the limits of their role since, by essence, they benefited from great freedom. According to relatively recent writings, even the king could be the object of their mockery. Just as the living sometimes complain about the non-fulfillment of their wishes despite prayers and offerings, the jesters then had a free rein to scoff at the gods. Because of their abnormal physical traits, the thoughts and gestures of the singers and jesters were also considered singular.

The photograph above shows a singer whose expression seems insistent towards the deity: is he imploring, praising, thanking? He alone carries the distress of a humanity never satiated with material or spiritual nourishment, love and freedom, alternating between the suffering of not having and the boredom of no longer desiring.

Here, for example, is the translation of a buffoon's tirade thrown in the face of the King, the Cambodian ladies and the French during the Water Festival of 1901 in Phnom Penh:

"Your women are beautiful, O Frenchmen, their complexion is white, and it is beautiful; but their noses are long, and those of our less beautiful women are short.

O women, you have what it takes for the joy of your husbands, do you not have it for mine?

It has rained a lot this year, the river has overflowed; there will be a lot of rice and joy. All the women will be pregnant by their husbands or their lovers. No matter.

In the time of Chaufa Bên, one had ten girls for a silver bar and five widows for a half-bar; now it takes five bars to have a girl and the widows have as much pretension as the girls.

We wear sampots and the French wear pants like the Chinese, but we wear our hair like the French and the French women wear it like the Annamites.

Cambodian women are in love all night, Annamite women are in love all day. It is said that French women are only in love in the evening.

O girls, remove your sampots, so that I may see which one of you pleases me the most.

I am ugly, I have a clubfoot, I have swallowed my teeth, and the bees come to deposit their wax in the corner of my eyes; my hair is kinky and my nostrils are black and dirty like the mouths of Annamite women. Yet there are five beautiful and young ladies who are vying for my favors.

Dogs greet each other by sniffing at the...., the French by shaking hands, and we kiss our wives by sniffing their face or breast..... it depends on the time.

O woman, I do not know what I have had for six months, it makes me hot in the chest when I see you, and I cry when I no longer see you.

O women, you are cunning, but I am in love; - you will take all my money, but I will take you for wives and you will cook your husband's rice; - you are cunning, but you will become pregnant and you will nurse my children; - you are cunning, but I will be the master of the house and you will be my servants; - you are cunning, but you will love and I will beat you; - you are cunning and to avenge me you will make me.... a cuckold."*

And the author adds in conclusion: "And the pirogues parade and the king smiles; the women laugh heartily, and it is a joy when one of the grimacing buffoons utters a well-turned ribaldry."

_____________

From: Bulletin de l'Ecole française d'Extrême-Orient / Year 1904 / Volume 4 / Number 1 / pp. 120-130. La fête des eaux à Phnom-Penh / Adhémard Leclère.

The ritual jester in Southeast Asian theater

"The role of comic characters intervening in theaters staging didactic stories and/or addressing religious themes is neither a new fact, nor an element specific to Cambodian theater. The presence of comedy in the royal performances of the Mahabharata and Ramayana epics was found in many South and Southeast Asian kingdoms, whether in men's, women's, or leather theaters (Epskamp 1993: 275). Even today, jesters retain an undeniable place in most of these practices. In India, several forms combining ritual and theater stage deities, including or not the possession of participants, alongside which jesters, the vidūṣaka, emerge (Tarabout 1998: 271-272, 274). Through their play, these clowns are led to perform or parody important ritual elements and their very presence can be perceived as a way of distancing themselves from the powers at play in the event and thus embodying them without risk (Tarabout 1998: 277-278, 289). These jesters can also attest to a state of affairs, such as the possession of a third party. It remains that their presence, beyond the amusement generated, is often ritual in these contexts (ibid.: 289). In fact, the comic sketches convey an object that goes beyond the framework of entertainment and contribute to the accomplishment of the cult. In another form of Keralan theater, Tarabout notes that the interventions of the clowns constantly transgress the social norms of interaction between characters of different caste or social status. However, the object of these sketches is not to challenge the hierarchical system and the pre-established order, but rather to reaffirm it year after year (Tarabout 1996: 362-363)."

_____________

* From the thesis of Stéphanie Khoury: "Quand Kumbhakār libère les eaux Théâtre, musique de biṇ bādy et expression rituelle dans le lkhon khol au Cambodge (When Kumbhakār Releases the Waters Theater, Bin Bady Music and Ritual Expression in Lkhon Khol in Cambodia)". January 2014.

Attempt at interpretation

As stated in the preamble, the underlying legendary Hindu or popular origin of these sculpted ensembles remains unknown. However, in light of Angkorian Khmer ethnography and epigraphy, we can affirm that the sculptors drew inspiration from a tangible reality: that of characters affected by genetic pathologies integrated into the highest spheres of society. Let us recall that these scenes are sculpted at the foot of the former royal palace. Although Angkorian society had hundreds of thousands of slaves fit for work, these individuals, who would be described as "disabled" today, were not set apart.

There is probably an exaggeration in having represented together such musicians, singers and jesters, whereas the iconography of the Bayon period (late 12th-early 13th centuries) generally shows characters with standardized physical traits in real situations.

A second interpretation could be to consider that certain celestial realms are populated by singular beings, fantasized worlds where one could express one's pain towards the powerful and the gods, insult them for the ills suffered, mock them and cry for vengeance.

These tableaux are like the cabinets of curiosities that appeared during the Renaissance in Europe, offering everyone the opportunity to reinforce their beliefs in unreachable worlds. Today, don't the mainstream media play a similar role with their supposedly "real" comments and images? These representations propose a distancing from difference, provoking both anguish and fascination, a form of catharsis perhaps.

The dwarf jester embodies this ambiguity between object and humanity, without being truly categorizable. He can mock the king and the gods, which no human would dare without risking his life. The jester makes the king and gods heroes capable of accepting the unacceptable. In return, humans must accept the troubles imposed by power and the gods. The jester bears, by proxy, the suffering of the people. As an object, he can be destroyed by royal power in the real world or the gods in the afterlife. Today, Facebook plays the role of outlet for the ills and tensions of Humanity, while video games, the world's leading entertainment, allow for the channeling of anguish by immersing oneself in an extraordinary, equally unreachable world.

Thoughts on disability

Angkorian society (c. 802-1432 CE) included many slaves. The servants of the temples - singers, musicians, dancers - were considered "supplies" in the service of the deity's cult, in the same way as ritual objects. By assimilating them to objects, any type of individual, regardless of gender, age or physical/mental condition, could enter divine service.

Contemporary Indian ethnography shows that some abnormal people are seen by Hindus as living deities. One can therefore assume that dwarves may have been considered "special objects" that could be mocked, but who in return had the power to rail at the king or the deities.

Although the legend that inspired these sculptures remains unknown, the sculptors, responding to a royal commission, transposed reality into the world of the gods by adding exaggerations such as the multi-headed animals.

Until the 20th century, commoner girls could be offered by their parents to the King of Cambodia from the age of eight so that they could become royal dancers or musicians. Once in the palace, they could only leave under drastic conditions. They were then subjected, in every sense of the term, to the will of the sovereign.

There are still geographic areas around the world in the 21st century where abnormal individuals are set apart, locked up, mistreated, eliminated or providers of organs for the most abject mafias. Disability (to use this trivialized term) is not reserved for those who suffer from a diminution of their physical or mental faculties, but also for those who are superior to the upper limits of their environment. There are also abnormal individuals because of their intelligence (memory, reasoning by flashes, mediumship, etc.) who are ostracized from society because they are potentially dangerous for the established power...