Last update: December 5, 2023

Historicity of Sbek Thom

- The term Sbek Thom ស្បែកធំ (pronounced sbaek thom), is the largest shadow theater in Cambodia. Another one, still in use, is the Sbek Touch ស្បែកតូច. The respective literal translations are "Large Leather" and "Small Leather". One and the other are differentiated, at first glance, by the size of their screen and the dimension of the leather figures. The first one shows large fixed figures, while the second shows small articulated figurines. At the second approach, the first one exclusively features the Reamker, Khmer version of the Indian Rāmāyana of Valmiki, and the second, popular stories, stories and, anecdotally, extracts from the Reamker.

The historiographic sources of Sbek Thom are rare. To go back in time, we first have to look for the traces of the Rāmāyana (Reamker) and its characters. The central character of the Rāmāyana is Prince Rāma (Ream), one of the avatars of the Hindu god Vishnu, who calls the Rāmāyana (Reamker). We mention here the two terms, Rāmāyana and Reamker, because the oldest inscription we know in Cambodia (K. 359, Veal Kanteal) dates from the 7th century and mentions the term Rāmāyana, not Reamker. On the iconographic level, the oldest representation of this divine personage dates from the same period. It comes from Angkor Borei in Takeo province.

Then as we get closer to the 13th century, which marks the end of Angkorian iconography, there is an explosion of iconographic evidence: Banteay Srey, Baphuon, Preah Vihear, Angkor Wat, Banteay Samrè , Bayon, Banteay Chhmar, Phnom Rung (Thailand) ...

The climax of this fireworks iconography dedicated to the Reamker is located in Angkor Wat.

But what are the sources attesting to the ancient existence of Sbek Thom?

In 1969, French ethnomusicologist Jacques Brunet wrote (our translation): “It seems that the figure of shadow, like the puppet, originated in ancient India from which it would have radiated, at the same time as the Indian civilization extended, particularly to the Far East, where shadow theater became very important in entertainment. Cambodia, hinduized during the first centuries of our era, quickly assimilated the Indian culture, as much in its techniques as in its thought: the Khmer civilization was born from the mixture of this culture coming from the outside and the local culture for lead to an original syncretism. (...) On the contrary (from Ayang or Sbek Touch), the Nang Sbek (Sbek Thom) joins the Royal Ballet in the great classical tradition of Cambodian theater. Like the Royal Ballet, it had once been part of the royal rites and entertainment given to the Court. Indeed, we are mainly present in the old royal capitals: Angkor, Battambang (a city that once housed a Siamese viceroy), Udong and Phnom-Penh, and always next to the royal dances of which it is somehow the complement .”*

The author also points out that the literal translation of the full name of this art form, namely “Robam Nang Sbek Thom” ie “dance-of-the-great-leather-figures”, does not relate directly to the notion of shadows. The practice, it is true, is not played with the projection of shadows in the manner of Chinese or Indonesian shadows, but with a play of contrast between light and darkness. However, the notion of ‘shadow theater’ is so deeply rooted in language habits that there is no need to question it.

* Nang Sbek. Théâtre d'ombres dansé du Cambodge. In Publication de l'Institut international d'Études Comparatives de la Musique. Berlin. 1969/

Ancient role of Sbek Thom

What was the old role of Sbek Thom? Once again, for the earliest periods, we must rely on the testimonies existing around the text of the Rāmāyana to enlighten the subject. The inscription of Veal Kanteal (K. 359, 7th century) reveals that the recitation of the Rāmāyana was a way of acquiring merit. The text mentions that a Brahman named Śri Somaśarman had an image of the god Tribhuvaneshvara erected and offered texts:

rāmāyanapurānābhyā- m aśesam bhāratan dadat

akritānvaham acchedyām sa ca tadvācanāsthim

Translation: “With the Rāmāyana and the Purāna, he gave the entire Bhārata and he instituted the recitation every day without interruption.” (Barth 1885: 30-31, K. 359, st. IV).

The text also states:

dharmmānśas tasya tasya syā- n mahāsukritakārinah

Translation: “May a part of this pious deed return each time to the author of the excellent deed...” (Barth 1885: 31, K. 359, St. VI).

The inscription K.218 (Prasat Sankhah, Battambang, 10th century) teaches us that the narration and the listening of the Rāmāyana has a purifying role. Knowing this, the king Suryavarman I wished to make sing the epics:

yadānanorvvīdhararājaśrṅgād

vinissrtā mrstajagatkalaṅkā

purānarāmāyanabhāratādi

kathāvivaksāmaradhāmasindhuh

Translation: “By desiring the recitations of the Purāna, the Rāmāyana and the (Mahā)bhārata, the celestial river is issued from the peak which is that face of the king of the mountains to cleanse the sins of the world.” (Coedès 1951: 51, K. 218, st. XI).

In their book entitled ‘Sbek Thom’ and produced for UNESCO in 2014, Kong Vireak and Preap Chanmara write: « Because it enacts only the Reamker, which contains sacred characteristics, Sbek Thom is performed at very reserved religious ceremonies associated with rites of invocation and prayers. Ceremonies in which Sbek Thom is generally performed include cremations of kings, royal family members, abbots and well-known monks; coronations; kings’ birthdays; royal ceremonies; markings of sacred boundaries of new Buddhist worship halls; consecrations of new Buddha statues; life-prolonging ceremonies of chief monks; and other village ceremonies. Currently Sbek Thom is also performed on other occasions, such as national days like the National Culture Day. »

In a video made in 1992 by the French ethnomusicologist Jacques Brunet, Master Ty Chean, one of the last living masters of Sbek Thom at that time explains that he is possessed by spirits and that people come to honor them.

Decline and revival of Sbek Thom

In his 1969's book*, the ethnomusicologist Jacques Brunet describes the current practices at that time and those already obsolete that took place twenty years ago (our translation): “The performance begins with a ritual ceremony whose purpose is magical: it requires to ensure that it will be done in good conditions (we invoke Vishnu and Shiva) and on the other hand we must give life to the characters that will appear. Three cries pushed by the dancers first call the deities to participate in the session: it is the beginning of the ceremony during which the master of the troupe, in front of the figures of Eysey, Preah Noreay and Preah Eyso, invokes supernatural powers. The following dance acts as an offering to the divinities so that they bring prosperity to the village in which one plays. Then comes the dance of Shiva and Vishnu, which symbolizes the struggle of good and evil. After that, while the orchestra plays the air of greeting, the master lights candles and sticks of incense which he fixes on the panels representing the Ascetic Moha Eysey, and the gods Vishnu and Shiva, then proceeds to ‘the awakening of the figures’. Equipped with a container of consecrated water, he rubs the eyelids of the faces of leather and then, with a comb and an ice cream, he proceeds to their toilet. At the same time, each dancer sprinkles with consecrated water to purify himself. After which, the spirits having taken possession of the figures, the representation of the Reamker begins. The leather panels here act as masks inhabited by spirits whose dancers are only terrestrial supports. Because of its unique style in Asia, thanks to the purity of its traditional canons, by its originality of expression which associates closely dance, sculpture, theater, music and poetry, the Nang Sbek of which it exists only a group today, retains a tradition with mainly Khmer aspects.”

The group to which Jacques Brunet refers in this text is that of Master Ty Chean, who died in 2000.

Kong Vireak and Preap Chanmara provide some clarifications that update Jacques Brunet's words: “Before performance, a ritual known as hom pithi, or sometimes khum rong, is performed. A panel depicting an Ascetic is placed in the middle of the white screen. A panel showing Preah Ishor shooting arrows is placed to the right of the Ascetic, while a panel portraying Preah Naray shooting arrows is placed to the Ascetic’s left. Other characters, such as Preah Ream and demon King Reap, flank the three principle figures. Ritual objects, including baysei, sla dhor, ripened banana, betel leaves, areca nuts, flowers, rice, incenses, candles, and a bowl of ‘sacred’ anointing water, are also displayed. The performers light incense to pay homage to the supernatural Masters, sampeah krou. Then the directing master starts to invoke to gods so that the Master of music, Master of narrators, and Master of panel handlers come to the altar. Next everyone bows to respect to the “presence” of the gods and the Masters.”

This excerpt shows a very sensitive cultural loss.

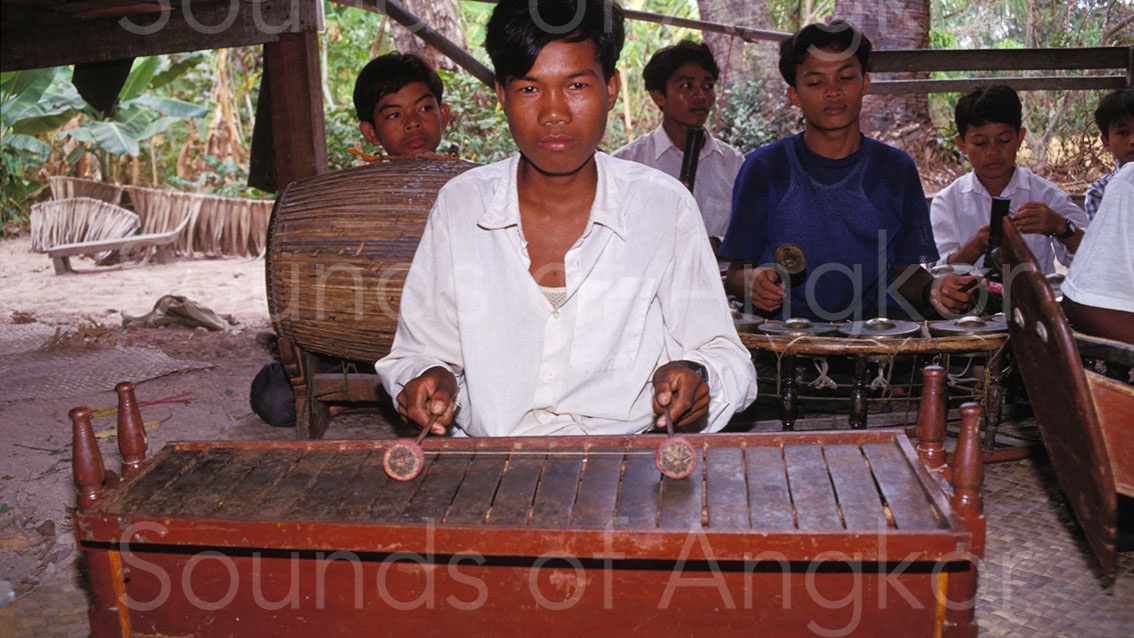

Hereafter, in order to testify to the historiography of Sbek Thom, some pictures from 1998 showing Master Ty Chean and his newly born troupe.

* Nang Sbek. Théâtre d'ombres dansé du Cambodge. In Publication de l'Institut international d'Études Comparatives de la Musique. Berlin. 1969.

At the origin of the disappearance of the practice of Sbek Thom

The Khmer Rouge revolution is generally pointed out, with reason, to justify the rarefaction or the disappearance of the artistic practices of Cambodia. But it seems that it goes differently for the Sbek Thom. Jacques Brunet informs us that the Master Ty Chean's troupe was, in the 1960s, the last (or at least one of the last) that counts Cambodia. He justifies the Khmer desires for the Sbek Thom by a very interesting testimony (our translation): “Currently (1960s) all the episodes depicted lasted seven nights. Beginning at eight o'clock, each session continues as long as there are enough spectators, often until late at night. Some twenty years earlier, it took sixteen days to tell all that tradition had preserved, several weeks ago. It is therefore no longer the full legend, but episodes chosen among the most famous. The troupe no longer has the opportunity to play very often (a dozen times a year) and the duration of major holidays being shortened, the troupe can only represent the popular episodes. She has, however, played seventeen nights in a row recently to celebrate the cremation of a venerable monastery.”

It is not the Khmer Rouge that destroyed this cultural heritage, but the loss of meaning for the Khmer people themselves. The contemporary survival of this art form is tied to the survival of Master Ty Chean himself and his restructuring effort after the revolution. If Jacques Brunet worked with him in the 1960s, he returned to Cambodia in 1992. In a personal communication, he says:

“When I came in 1992 to make a film about the Royal Ballet with a video about the Nang Sbaek, the Fine Arts lent me the skins that I took to Siem Reap by plane a few days, the time of filming . In one week, Ty Chean assembled a troupe with the village youths, making them work five or six hours a day for an unexpected result. They danced three nights in a row for four hours each time, it was amazing because we had found the way they danced in the sixties. A real joy ! It was thanks to that week that this 'memory' could be restored."

As for us, we were fortunate enough to meet Master Ty Chean in 1998 before he disappeared in 2000. At that time, he had gathered around him, his son, his grandson and children from Siem Reap. Every day, musicians and manipulators repeated under the watchful eye and the uninterrupted presence of the master.

The classification of Sbek Thom by UNESCO as World Heritage of Humanity has of course contributed to the revival of this art. The troupes have multiplied, created by individuals who have detached themselves from troupes in activities. It must be recognized that in a country as poor as Cambodia, the creation of a new troupe represents a tour de force. It is indeed necessary, to create an orchestra with its multiple instruments, to make the numerous leather figures, to repeat intensely, to ensure the marketing to attract the tourists ...

Today, the various troupes of Cambodia are in front of the beds of tourists ignorant of both Sbek Thom and Reamker. The sessions last at most one hour. The troupe at Wat Bo Pagoda, in Siem Reap, offers one of the most iconic shows in staging. Several elements contribute to the magic of the moment: the quality of the reception of the public, the environment of the pagoda, the use of a fire fueled by coconuts and an electric light. All this creates a magic to which the spectators are particularly sensitive. The quality of the seat in front of the screen and the low number of invited spectators also contribute to create a feeling of privilege for the one who lives the moment.

Sbek Thom and its internal religious practices

In the 1960s, Jacques Brunet testified to religious practices related to the Sbek Thom (our translation): “Many taboos are still observed today during performances, and the incantatory rites that preceded are performed with great care and attention to detail or serious illness for the dancers. Leather figure dancing sessions are also organized to bring down the rain or to hunt an epidemic. This is to say the fear awakened by these figures, some of which can only be touched by the dancers themselves.”

The design of the leather figures is also the object of offerings from manufacturers to protect themselves against the evil power of certain deities. Jacques Brunet testifies also: “Before starting a new series of drawings, the artist must make an offering ceremony to reconcile the god of craftsmen, and at the same time remove the harmful powers associated with certain figures, especially those of Shiva and Ravana who have the faculty of bringing misfortune to the one who draws them if the prescribed rites are not well observed. For example, a sign must never be completed during dawn or dusk, and during the night work can only be done with the flame of a torch or a blaze.”

Film : Du Ramayana au Reamker… à la lumière des ombres

A film in French by Patrick Kersalé. The Reamker is the Khmer version of the famous epic of Indian Ramayana. From the 10th century, he is represented in the bas-reliefs of Hindu temples in Cambodia. It has been transmitted by the oral tradition to the present day despite the vicissitudes of history and survives today thanks to the tenacity of a handful of men animated by a foolproof faith ...

Published versions of the Reamker / Râmakerti

There are two written and published versions of Reamker or Râmakerti and an isolated episode (You can refer to the original version in French by clicking here):

- Ramaker ou l’amour symbolique de Ram et Seta, François Bizot. Publications de l’École française d’Extrême-Orient. Paris, 1989. French translation condensed from a Mi Chak narration recorded in 1969 who had himself learned from a manuscript found in a pagoda near the Angkor Wat temple.

- Râmakerti II, Saveros Pou. Publications de l’École française d’Extrême-Orient. Paris, 1982. Traduction d’une version écrite incomplète.

- Un épisode du Râmâyana khmer. Rāma endormi par les maléfices de Vaiy Rabn. Khing Hoc Dy. Collection « Recherches Asiatiques ». Editions L’Harmattan, Paris, 1995.

There are two other written but unpublished versions in Khmer; one belongs to the Ty Chean's troupe, the second to the Wat Bo's troupe, both in Siem Reap. Each of these versions is respectively known by three members of each troupe.

The main characters of the Reamker

According to the cited authors and the reference period of the texts, the spelling of the names of the characters varies. We list below the names of the names between the Reamker and the Indian Rāmāyana of Valmiki and mention their nature.

The old kings

- Dasarath = Dasharatta, king of Ayudhyâ, father of Ream.

- Janak = Janaka, king of Mithilâ, adoptive father of Seda. He receives Ream to undergo the test of Shiva's bow, after which the young prince will become the husband of Seda.

The old princesses

- Kokalyâ = Kausalyâ first spouse of King Dasarath, mother of Ream.

- Sramut, spouse of King Dasarath, mother of Lak.

- Kaikesi = Kaikeyi : mother of Bhirut (= Bharata), second spouse of King Dasharath.

Young princes

- Ream or Râm = Râma : incarnation of Vishnu, first son of Dasharath and Kausalyâ.

- Lak or Laks= Lakshmana : Ream's younger half-brother, his favorite.

- Bhirut = Bharata : son of Dasharata and Kaikesi, half-brother of Ream.

The spouse of Ream

- Seda or Sitâ = Sitâ, spouse of Ream.

The dignitaries of Langkâ (the present island of Sri Langka)

- Reap, Râb, Râbn, Râbanâ or Dasamukh (literal "king-to-ten-heads") = Râvana : King of the yaks (râkshasas), sovereign of Langkâ.

- Surpanakhar = Shûrpanakhâ : daughter of Reap.

The monkey princes

- Hanumân : White monkey, General of the Army of the Monkeys, Son of the God of the Wind, Brah Bay and the Guenon, Añjan, Ream's Servant. Also named Bâyuputr. Famous for his prodigious feats, he is still today the object of an important cult throughout India.

- Sugrîb = Sugriva : Uncle of Hanuman King of the monkeys, Son of the Sun. He brings the help of the monkey people to Ream

- Bâlî = Vâlin : Elder brother of Sugrîb. After a fierce fight with the latter, Ream killed him by an arrow.

Sound tools through the texts of the Reamker

In the Reamker, there are several times reference to sound tools. We prefer here the name ‘sound tool’ to that of ‘musical instrument’ because in many cases, it is more objects for communication than music proper. Sound tools have several roles:

- Communication serving the military strategy,

- Entertainment,

- Creation of an atmosphere,

- Communication with the virtual world.

In general, the musical instruments mentioned in the different versions of the story represent temporal markers. The narrator must indeed adapt the name of the musical instruments to his own time. These terms thus constitute adjustment variables between the original text of Valmiki's Rāmāyana and the Reamker. Even within the various versions of the Reamker, these elements change. Beyond the story, the musical instrument has also adapted to their time in painting and sculpture. It must be borne in mind that musical instruments represent a foreign world for ordinary people. As in the world of life, they are born, transformed and die. Wars erase some of the memory. Others, acoustically more powerful, more practical, more fashionable, borrowed from other cultures, replace those in use. Then the memory of the latter disappears. The monsoon climate eventually destroys wood, bamboo, calabashes, leather, horn. The names themselves sometimes disappear from the memory of men or manuscripts on oles. What remains then as a model for the painter or the sculptor if not his own environment to draw inspiration? Individual instruments and instrumental ensembles left in testimony over time by visual artists allow to sketch a chronology of their history.

The story also refers to songs, incantations and cries. Likewise, reference is made to dance, a major art form among the ancient and contemporary Khmer people: celestial, rejoicing or martial dance.

References to sound and dance

Let us first list the evocations related to the sound world and to the dance in the reference works mentioned above. We classified them by genre in each of the three books consulted: war and martial parade, entertainment, funerals, distant communication, atmosphere, magic. We postpone the authors' translations with partial corrections when it seems necessary. Indeed, the authors are not themselves musicologists, misinterpretations have sometimes been detected by referring to the original text in Khmer. We have also completed the translation by putting in front of the name of the organological typologies, a transliteration of the original term. May this transgression at the service of right knowledge be forgiven here!

War and martial parade

Ramaker or the symbolic love of Ram and Seta (Ramaker ou l’amour symbolique de Ram et Seta)

- p.76, chap.12. “The demon ran to complain to King Khar, who had the war drum beat to announce his vengeance; the sound of the lightning was heard.”

- p.79, chap.16. “When Brah Isur saw the decline of his palace, he rang the gong and beat the drum.”

- p.89, chap.33. “The war drum rumbled and one went out weapons and mounts (...) Then one heard like the crash of thunder in the clouds; Sri Laks, Hanuman, Nil Ek, Nil Bejr and Nil Khan raised the eighty thousand of monkeys, in a noise of cries and music. Le tambour de guerre gronda et l’on sortit armes et montures (…)”

- p.92, chap.36. “Some monkeys held a sword, others a club, others made music, danced or struck long chaiyam drum. (...) The hammering of the gongs broadcast on a deafening wave a thunderous buzz.”

- p.96, chap.43. “Rab beat the war drum. Yaks poured in from everywhere, piling up in the city. Indrajit took out the eight-headed elephant, with tusks like chariot wheels, surrounded by parasols, large round fans, curved screens, gilded screens and staggered parasols; the gongs scattered their dull vibrations in the distance and gods surrounded the procession. (...) At the sight of the carnage, Indrajit escaped on his elephant and took the appearance of Brah Indr; celestial dancers moved with grace to its sides and gods played music with strangely beautiful accents.”

- p.98, chap.44. “The war drum was struck, and the Yaks brandished their arms, crying out in the crowd of ibexes, camels, donkeys, lions, tigers, buffaloes, and rhinos, their mounts; twelve seas, in all, indomitable warriors.”

- p.103, chap.52. “Earing the sound of the war drum, innumerable troops piled up in a compact multitude; the earth trembled.”

- p.109-110, chap.65. “The next day, Brah Ram made a sortie, in a deafening noise echoed in the distance; some monkeys were banging on chaiyam drums, others were jumping backwards, feigning passes, holding mortar between teeth, sketching dancing figures or displaying an aggressive face. Hanuman walked on them again and the Yaks wielded sticks, sabers and banners behind him.”

- p.112, chap.69. “The next day, Thāv Cakravât, shorn like his subjects, burst into violent anger and beat the war drum. He gathered in a crash of thunder a multitude of ferocious warriors.”

Râmakerti II

- p.192/500. “The soldiers of the four army corps strike the gongs (ku' kong) and the war drums (tung), shout in chorus, echoing in all the regions.”

- p.194/529. “They beat the drums (tung skor) and the gongs (tung kong) frantically, while the officers release the horse.”

- p.224/974-975. “As for the horsemen, they prepare superb harnesses, attach gleaming saddles to the horses' backs, and pretty fringes under their chins, bells, headboards, martingales and other belts encircling the belly and the belly of the beasts: so much brand new accessories to escort the Master of men in his glory!”

- p.225/987. “The soldiers of the four army corps and their leaders sound the drums of war (ku 'kong), and parade bellicously to the sound of music (phleng kto ktia).”

- p.259/1499. “Musical instruments are brought together: trumpets (traê), conches (siang), drums (skor) and gongs (kong). "(In this context, rather military parade).”

An episode of Khmer Ramayana (Un épisode du Râmâyana khmer)

- p.15/3. “An orchestra of trumpets and conches resonates as melodiously as that of paradise.”

- p.21/74-75. “Vaiy Rann, who wears ornaments as splendid as Brahma, rides on his precious vehicle, sheltered from parasols [and accompanied by] an oboe orchestra. The coachmen direct [the tanks] in procession.”

- p.28/137. “The beats of the big drums sound, they sound very far and make the earth tremble.”

- p.28/140-141. “Demons in fury dance, move rhythmically holding naga, and metamorphose. [They hold] guns, swords, shields, bows and crossbows in large quantities. These demons push ‘cries of victory’.”

- P.32/181. “The music resonates and sounds harmoniously far away.”

Entertainment

Ramaker or the symbolic love of Ram and Seta (Ramaker ou l’amour symbolique de Ram et Seta)

- p.102, chap.49. “The monkey (Hanuman) then went to reign in the palace of the naga and spent several months there, settled among the women of the harem who danced and sang for him, while others massed and hastened to his side.”

Râmakerti II

- p.156/11-12. “Laks sits in front of Earth Support. The coachman sends the chariot to the melodious sound of orchestral instruments and singing of sebâ1, while the ministers, the officers, the well-aligned soldiers, escort the supreme sovereign in the direction of the forest.”

- p.157/23-25. “The women dive into the pond and reappear by jostling each other; they scream for joy, they clutch for teasing, they make jumping bets, they throw water with both hands on their companions who try to slip away, they swim and hit the water for the to throw back, they dance, they sing melodious songs, they imitate the musical instruments.”

- p.191/495. “At the same time, the orchestra composed of drums - skor toap drums of war, Javanese drums skor tung, tambourins2 skor chüia - and tâkhe play pleasant and harmonious tunes.”

- p.194/539. From an original French translation revised: “Parasols with tiers are wide open to shelter the dear princes, while trumpets (traê), conches (siang), flageolets (?) (rokiang) and oboes (sralai) unite their sounds harmoniously.”

- p.225/981. From an original French translation revised: “And the pin peat orchestra, trumpets (traê), conches (siang), oboes (sralai), Javanese drums (skor chüia), and Môn tambourines (skor ngia) begin to play occasional musics.”

- p.257/1469-1471. “Following this, the king gives the signal of the public entertainments and other games: representations of Râmakerti3, yantrī4, cut leather theater, yīke5, Khmer jumps, mortar games, mangram6, lân’ thân (?), tightrope, shooting … Chinese dances, Annamese hât boi opera, jâtrī7 dance, Javanese entertainment, shield games, boxing, elephant fighting: so many games!”

- p.259/1489-1490. From an original French translation revised: “In the morning, when the king goes to the courtroom, the musicians make him music - pin peat, drums, gongs, (trumpets and conches) prokum - to welcome him, while his brothers and a multitude of dignitaries and officers lined up at his side.”

1. Originally "lullaby song". By extension, means any soft music for royal entertainment. (Author's note)

2. bīn bâmn, "tambourine", ramanâ, "other kind of tambourine". (Author's note).

3. The lakhon khol, or simply the khol, is the mime theater dedicated to the representation of Râmakerti. (Author's note).

4. Puppet. (According to the author's note).

5. Sung theater form of Malayo-Polynesian origin. It arrived in Cambodia by way of Siam at an unknown time. The majority of classical yīke songs are in a particular language, a mixture of Javanese or Malay, Siamese and Khmer, incomprehensible to current Khmer speakers. (Author's note).

6. An orchestral ensemble consisting of a large barrel drum, a flat gong, a bossed gong, an oboe and a bamboo flapper. (According to the author's note).

7. Texts show that the jâtrī theater was known in Cambodia in the 18th century, certainly introduced from Siam. Indeed, there is in Thailand a type of jâtrī theater, famous in the south of the country, consisting of an exclusively male troupe, whose repertoire is devoted to the history of Prince Sudhan and nymph Manorâ. (...) In Cambodia, the jâtrī theater has fallen into oblivion, but the novel Brah Sudhan is still famous there. (According to the author's note).

Funerals

Ramaker

- p.123 chap.82. The funeral ceremony. “During the vigil, the funeral accents of music would put the heart in mourning, while the religious recite the stanzas of Pansukul. Then Brah Ram would slip into the shining golden urn, amid the lamentations, and Hanuman would seek Nan Seta.”

Râmakerti II

- p.268/1615-1616. “The king sends his favorite women, in whom he has great confidence, to tell the old dungeons and all the other women to take mourning clothes, and recite the funeral lamentations according to the tradition of the princes.”

- p.271-272/1665-1671. Example of a funeral lament pronounced by Sita for her husband Rama, whom she believes to be dead. She laments thus: “O my dear friend! Why did you leave me? May I also die to unite with you (again!). Your benefits to me are inestimable, even heavier than the great ocean, thicker than the great earth: nothing can match them! Oh ! All three, exiled from the kingdom, we wandered in the forest, enduring punishments of a thousand kinds, having for their only nourishment the fruits of the trees, and dressed as ascetics! Then the demon Dasamukh took me away to take me to Langka. With ingenuity, you made a pavement, my prince, to cross the sea to your monkeys. You make war on the demons, and the annihilation to the last. Then it was our reunion, the treasure of my heart, and you brought me back to Ayudhya. A wicked and mean villain cunningly succeeded in making me draw the image of Râbanâ: it was my loss!”.

Remote communication

Râmakerti II

- p.157/274-275. “At this moment, seeing the princess Sita delivered, the sovereign Kosiy, the great Indr, breathes in his conch a sweet and melodious air that resonates between the trees.”

An episode of Khmer Ramayana (Un épisode du Râmâyana khmer)

- p.48/346. “Khun Nīl (ape-general) strikes gongs to warn others, saying, « When the morning star comes up and shines, the royal misfortune will completely dissipate. May all the soldiers constantly watch over the precious sovereign. Having heard this perfectly, Vaiy Râbn flies away and reaches heaven.”

Ambience

Râmakerti II

- p.254/1434. “The musicians play tunes of sweet and nostalgic music to accompany the songs, like a divine concert to the glory of the king.”

- p.256/1463. “All this is bristling with pretty umbrellas spread out, fly-whisks, pai man’, circular fans, on a deafening background of music and human cries.”

Magic

An episode of Khmer Ramayana (Un épisode du Râmâyana khmer)

- p.43/297. “There will be a very powerful demon who knows how to recite incantations according to the magic arts. At the moment, when you fall asleep, he will secretly attempt to desecrate your power, manage to seize your person, and go down to his house.”

- p.47/337. “He recites divine mantra stanzas, turns into a monkey, sneaks.”

Analysis of textual elements

What strikes at first glance is the role of certain musical instruments as tools of communication, of which the voice is of course part. This communication is exercised in these three spaces.

- Communicate here: Entertainment music nurtures conviviality between humans. Offered to both important characters and the public, it is one of the pleasures of life alongside dance and massage. Women in the bath imitate musical instruments; in this regard we don't know more but it could be aquatic percussion as it is still practiced in black Africa and Latin America. On several occasions, the narrative insists on the harmonious character of the music. Precious and honorary objects (umbrellas, canopies, fly-whisks ...) complete this voluptuous decorum.

- Communicating over there: we are referring here to martial music. Its role is threefold: to galvanize combatants, to frighten the enemy and probably also to communicate maneuvering orders. Powerful instruments like conchs, horns and gongs are clearly designated.

- Communicating beyond: the voice (word, song, mantra recitation, lamentation) is the appropriate communication tool to get in touch with the dead and divinities.

Musical instruments and voice

Most of the musical instruments mentioned in the stories are traceable over time in the territory of Cambodia itself. They are represented in the bas-reliefs of ancient temples, mentioned in the lapidary writings of the pre-Angkorian period or found in excavations. Almost all of these instruments, as well as vocal forms, remain alive in contemporary Cambodia or elsewhere in Southeast Asia.

Correlation between the musical instruments of the texts and those of Angkorian iconography

Reamker narrators have adapted the names of musical instruments and sound tools to their immediate environment. Indeed, even if the epic is old, the narrators have adapted them to their time and public. Musical instruments are technological objects that have evolved throughout history in modifications, local inventions or the adoption of exogenous objects.

The Angkorian iconography offers us many paintings dealing with the Reamker. Most of the pediments of the vast temple of Angkor Wat as well as its west gallery, north wing (Battle of Langka), refer to it. Regarding the representation of the music, there are only martial orchestras in which the musicians are either men or the monkeys of the army led by Hanuman and raised by Prince Ream. Thus, referring to the preceding chapters only the rubrics ‘war and martial parade’ and ‘distant communication’ are treated in Angkorian iconography.

We have dedicated a complete chapter on this topics, available in here.

The manufacture of figurines as a social springboard

When we look at the souvenir market for tourists in Cambodia, part of the offer is made up of leather engravings ranging in size from the key ring to the large decorative panel, to the great figures of the Sbek Thom (though rare) and the figures of Sbek Touch. At the origin of this market offer, a man: Sery Rathana. Here is a summary of his action. You will also find below a video that summarizes his action.

When Sery Rathana became an orphan at the age of nine, he sold cans and sand from the river, and cut wood so his three brothers could attend school. He has only a ninth-grade education. Later he attended the House of Peace Association, where he learned the skill of ‘skin carving art’. He was so talented that he himself became a trainer. Then, in 2002, with his own savings, Rathana opened the Little Angels Orphanage, outside the Preah Ko temple, in Siem Reap’s Bakong district.

Little Angels shelters, educates and trains orphans and children from impoverished families in the craft of leather carving. Little Angels, which originally housed 5 children, now has 80, 50 of whom are orphans and 30 whose families are too poor to support them.

When families approach Rathana for his help, he interviews them to see if the child qualifies to be part of his program. Because of a lack of space, the orphanage has only 10 girls.

The ‘angel’, aged from 5 to 25, have a structured life like any other child. “All students have to go to school to live here,” says Rathana, which is why the students are on a rotating schedule. Thirty-five of the children will stay at the orphanage and learn how to draw or carve, while the other 45 attend.

As the students receive 20% of the proceeds from the sale of their art, some choose to go to private schools.

When they return from class, the ‘Angels’ can play sports, work on one of the five computers that Rathana saved up for, have free time, or do their homework.

In the afternoon, English classes are held, taught by a former ‘Angels’ who is now a clergyman and a university graduate.

Rathana, who receives little aid, relies on tourists to support his orphanage, and 45% of the profits from art sold are used to buy supplies to make more art and continue the adventure.

In this video, discover how cowhides are prepared for Sbek Thom, Sbek Touch or tourists' souvenirs.

In this video, discover how Sery Rathana has been organizing since 2002 to teach engraving to orphans and poor children.

What future for the Sbek Thom?

The disinterest of the Khmers for Sbek Thom is linked to the loss of meaning. We have seen that in the sixth century, according to the inscription K. 359 of Veal Kanteal, reading or listening to the text of the Rāmāyana had purifying virtues and allowed to acquire merits. We also understood that the Sbek Thom was borrowed magic at all stages of his life (manufacture of leather figures, ceremonies prior to performances, possession of master figures by spirits). All these ingredients remain in Cambodia in various Buddhist and animist practices. The Buddhist texts in pali are virtuous and / or magical; possession remains a social component through arak ceremonies where medium-exorcists are possessed and consulted by the entourage during specific ceremonies. The ceremonies prior to each performance of music, theater or dance are unavoidable. Important homage ceremonies to the living and deceased masters (sampeah kru) continue to be performed outside performances by artistic troupes, in all disciplines.

All of these rituals and beliefs are therefore an integral part of Khmer culture. So why are the Khmer themselves not interested in Sbek Thom?

We propose to engage with the leaders of the main Sbek Thom troupes and the Buddhist authorities to determine if the text of the Reamker and, in its wake, the Sbek Thom, could be reborn from the ashes. Recall here that the Rāmāyana (Reamker) is a virtuous text that has shaped Khmer society for nearly a millennium and a half. So why should all this stop?

We know that the Sbek Thom is in competition with the Sbek Touch, although both have had different roles in the past. The latter is obviously more popular and directly understandable by the masses. It is an easily accessible entertainment that is not bound to deep beliefs from the public's point of view.

It must of course be admitted that the maintenance of a shadow theater troupe has a cost that neither the people nor the Buddhist institutions necessarily wish to assume. And even if they wish, the acquisition of know-how takes many years and requires a lot of energy. But money is not lacking, even in Cambodia. Rich patrons spend money to build pagodas and maintain monastic communities. So why not Sbek Thom's troupes?

To think that the Sbek Thom can culturally survive because he was classified by UNESCO is a fantasy. The troupes receive no subsidies from this institution. And even so! Money can not maintain the "Permanence". The Permanence speaks for itself by the play of the necessity of a belief or an object. This need no longer exists because of a loss of meaning. To think that the tourism market and international productions can maintain the permanence of the Sbek Thom in the long term is also an illusion ...

The future of Sbek Thom can only be achieved by reactivating beliefs with the support of the Buddhist authorities.

Bambu Stage: the revival of the shadow theater

In Siem Reap, Bambu Stage's shadow theater troupe has been innovating since 2013. An international and Cambodian team has created several shows mixing various artistic know-how (Sbek Thom, Sbek Touch, shadow theater itself with live characters and artifacts evolving at varying distances from the screen, theatrical play in front of the screen) and different technologies (lighting, video projection, subtitling). The other peculiarity of this innovative form is to address both a local and international audience (Khmer subtitled and English language). In the philosophy of Bambu Stage, an art form that addresses only a foreign clientele leads to the destruction of the local culture.