Last update: December 5, 2023

His Majesty Sisowath ស៊ីសុវត្ថិ (September 7, 1840 - August 9, 1927) was the son of King Ang Duong and half-brother of Prince Si Votha and King Norodom. He remained on the throne from April 27, 1904 until his death in 1927. It is precisely the ballet of this sovereign that will make forever the dance of Cambodia famous in the West, since his dancers were invited to the Colonial Exhibition of Marseille in 1906. On this occasion, Auguste Rodin realized about 150 paintings.

At the time of King Sisowath, the ballet lost its primary role which was to dance for the gods. It mainly performed for the monarch's guests as choreographic performances and masked theater giving excerpts from the Reamker. The two film excerpts below testify to the state of the dance at that time, which George Groslier already described as deliquescent in relation to the court of H. M. Norodom. According to its own figures, the troupe of King Norodom (1860-1904) was rich with five hundred dancer-actresses; under S. M. Sisowath, it will be reduced to a hundred.

Here we will compare the animated images with the words of G. Groslier published in "Danseuses cambodgiennes anciennes et modernes" in 1913.

King Sisowath's dancers (1)

This short 1910 film, produced by Pathé Baby, gives us an idea of the costumes and tiaras of the dancers in King Sisowath's court.

G. Groslier writes: "Between the women sitting on the ground, and singing as they open large black betel mouths, the apparition is marvelous. On one side of its high two-storey red gold tiara, thin as a sword and built like a tower, a jasmine and camp pendulum swings. The dancer's face is round and white as a drop of milk. Her eyes with drawn eyebrows look at nothing and nobody, but seem to follow in front of them the invisible model who sets the complicated poses. Her mouth is deep and closed, her head motionless on her right torso, in the shimmering scarf, her arms bare, the legendary princess advances. The clacking of the pieces of wood regulates her steps and the music supports her." (original in French)

The orchestra

At 1'03, three instruments of the pin peat ensemble (as they are known today) appear stealthily: roneat ek, kong vong thom and roneat dek. Then, at 1'11, the roneat tung, the skor thom, the sralai and behind, the kong vong touch player whose instrument is hidden.

Reconstruction of the pin peat ensemble from two shots of the film.

G. Groslier writes: "Sitting at the center of small gongs arranged in a circle, on which they strike with two felted mallets, in front of large timpani held at an angle by wooden X's and junk-shaped xylophones, graceful and curved on their square feet, the musicians occupy a whole side of the long dance hall. (...) The instruments are very beautiful, made of precious woods inlaid with ivory and graceful shapes." (original in French)

Singer and claves

The female singers hit long wooden claves. This video allows to see the original, a close-up shot and then a slow motion.

G. Groslier writes: "The knocking of the claves not only shouts out the words of the singers and the gestures of the actresses, but also marks the first beat of the musical measures."

King Sisowath's dancers (2)

This film, produced by Indochine Film (ICF) during the reign of King Sisowath, is didactic. It shows in detail both the pin peat orchestra and the dancer-actresses. Below is a brief analysis of the images based on the time codes.

- 0:05 - Dancers sitting and pin peat orchestra.

- 1:01 - Roneat ek xylophone; kong vong thom and kong vong touch gong chimes.

- 1:11 - Sralai oboe and samphor drum.

- 1:30 - In the foreground, the kong vong touch and in the background, the kong vong thom. One will notice the faster and fuller playing of the former.

- 1:42 - Skor thom double drum .

- 1:53 - Eight dancers on two lines. Compared to today's Royal Ballet, the body movements are ample, the steps long, the arms high, the movements fast, the heads more inclined.

- 2:33 - Narrative dance. A female character and a male (played by a woman) lead the story.

- 3:30 - Masked martial dance. Male characters embodied by women. Reamker episode.

- 4:33 - Six female dancers.

- 5:13 - Masked character : Krong Reap

- 5:22 PM - Dancer with white face. At this time, a layer of white blush masks the personality of the dancer while the eyebrows are highlighted in black.

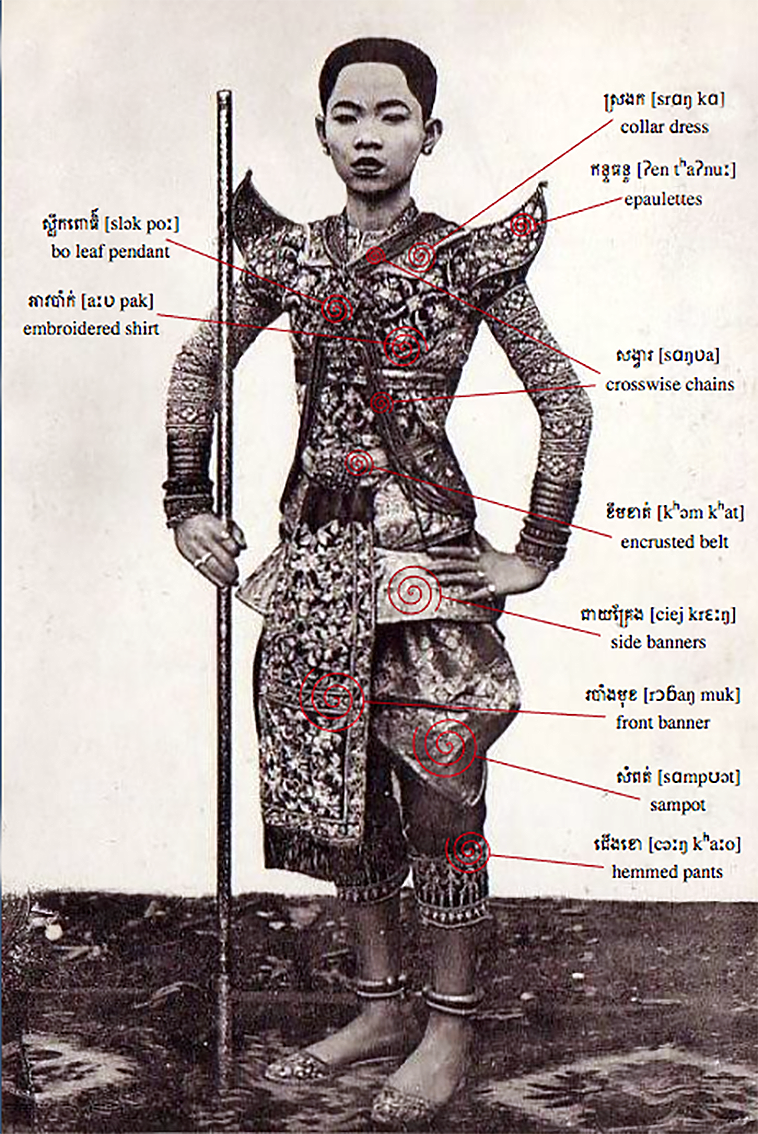

- 5:35 - Detail on the bracelets, the sleeve and a mudra.

- 5:41 - Close-up on the dancers and costumes.

About the quality of the dance

In these fragments of dances, we can see a certain number of approximations that can be justified by a writing by G. Groslier: "When the dancer has finished her education, she attends less and less rehearsals. In the disciplined times of H. M. Norodom, they regularly attended three exercises a week. Even the first dancers were present. But now that everything is lost, that everything goes away, the dancer works less and does not maintain her difficult flexibility anymore. It's only just if there are, before the holidays, some serious rehearsals, from which no actress is exempt." (original in French)

G. Groslier writes: "The Khmer dancer is an actress, a mime. She represents a legendary character. She expresses the feelings and represents the actions sung by the women's choir sitting along one side of the room. Each sentence of the singers solicits a gesture or determines an attitude of the dancer, always mute. These attitudes, these gestures are ritual, unique and have been transmitted from generation to generation without any didactic, written and precise model. (...) All human feelings are expressed by Cambodian actresses with remarkable truth, precision and plastic simplicity. If the physiognomy of the mime remains serious and impassive, all her body flexible and exercised, her hands that freeze or fly away in cadence, exteriorize and materialize the concerns, emotions, sadness and joys of her soul that fill the wonderful words of the singers. (...) She is white, because, having become an ideal princess, she must no longer have anything personal, of what she was, a simple woman, before the dance; there must be nothing left in her of the humanity she left, and whose rites and sacred rules momentarily separate her. She must be rid of all triviality. Desires, sensuality, jealousies must exhale as they hit this marble mask with hermetic lips. This officiant is no longer a woman, but a divine statuette, slowly animated by the Art, the beliefs, the past of a people who admire and venerate in her the most beautiful of her conceptions and the most perfect expression of her cult and her life". (original in French)

The dancers at the Colonial Exhibition of Marseille (1906)

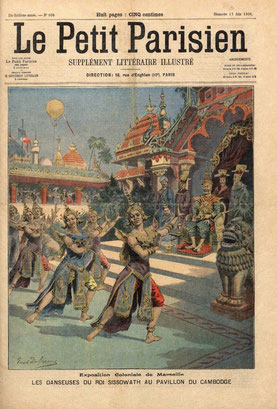

This cover of Le Petit Parisien is dated June 17, 1906. The image is subtitled: Colonial Exhibition of Marseille. LES DANSEUSES DU ROI SISSOWATH AU PAVILLON DU CAMBODGE - THE DANCERS OF KING SISSOWATH AT THE PAVILION OF CAMBODIA.

It shows six dancers. On the right, on a throne, King Sisowath in Khmer ceremonial costume. Behind him Vietnamese mandarins. A pre-Angkorian style lion guards the entrance of the building.

This cover of the Petit Journal is dated June 24, 1906. The picture is subtitled: A L'EXPOSITION COLONIALE DE MARSEILLE - AT THE COLONIAL EXHIBITION OF MARSEILLE. The "Dance of the Nymphs in the Forest", performed by King Sisowath's dancers.

It is strange to note that the musicians are Vietnamese; we clearly identify two đàn tranh zithers and the neck of a đàn nhị or đàn cò fiddle. Behind them, a man with medals is wearing a bowler hat and a Khmer sampot. In the background, on the right, a four faces tower of Bayon temple; on the left, a pastiche of a French building with a stupa-shaped roof finished with nagas.

Auguste Rodin and the dancers

In July 1906, Auguste Rodin (1840-1917) met for the first time the King Sisowath Ballet in Paris during its performance at the Pré Catelan theater. Ecstatic in front of the beauty of these dancers and the novelty of their gestures, he will follow them to Marseilles where he will draw them relentlessly, until their departure on July 20th. He confided his impressions to Georges Bourdon, published in the Figaro on August 1, 1906: "These monotonous and slow dances, which follow the rhythm of a hectic music, have an extraordinary beauty, a perfect beauty... [The Cambodian women] taught me movements that I had never encountered anywhere else...".

Rodin's works are executed in gouache. There is no need to look for the Khmerness of the costumes because the artist's intention is to banish clothing, physiognomy and hairstyle. The only thing that remains is the concentrated energy of gestures that have their roots in ancient India, metamorphosed by the aesthetic tastes of the entire lineage of Khmer kings and under the rule of generations of dancing mistresses. Most of these works are today the property of the Musée Rodin.

The difficult training of dancers

George Groslier writes: "From the age of eight, the 'lokhon' begin to work. Every day, for at least a year, from eight in the morning to eleven, and from two to five in the afternoon, they practice under the direction of female teachers, former dancers. This preparation is long and painful for these poor little ones. The rehearsal room is sad; the air is so often stifling! Sitting on the floor, they make twisting and turning movements of the torso on the pelvis; or, placed one in front of the other, they turn their fingers on the back of their hands, until all the phalanges crack. Finally, still practicing between them, one takes the other's arm and twists it back on his knee like breaking a branch! It is necessary to remove the elbow joint, to reach this hyperextension of the forearm on the arm (...) And when her body will be enough petrified, and that she will be able, unfolding her arm abruptly, to make it crack in an unusual reversal, only then, the little dancer will learn her roles". (original in French)

Ballet organization

George Groslier writes: "The corps de ballet is placed under the direction of the princess, the King's first wife. She is its absolute mistress, orders punishments, regulates discipline, supervises rehearsals, pays the balances and ensures the regularity of His Majesty's service. (…)

H. M. Sisowath's current corps de ballet consists of eight principal dancers; sixty-six to seventy subjects and about forty girl students.

A principal dancer earns thirty-five piasters per month; the ordinary dancer earns ten to fifteen piasters depending on her role. As for the girls, their sales vary from three to six piasters.

From this salary, each actress takes four piasters for her food. When there is a dance session, she receives a supplement. It is of one piaster for the first dancer; for the difficult roles, the mask wearers, from fifty to ninety cents; for the ordinary subjects, twenty-five cents and for each little girl, twenty cents.

So many numbers and modest figures!... But, at the end of the year, all this little world, musicians, women and choirs, dressers, costs, with the costumes, to the royal budget, thirty to thirty-five thousand piasters." (original in French)

Royal service

George Groslier writes: "The King's daily service is provided on a rotational and shift basis. It is composed of twenty dancers and a few musicians. The most beautiful of the troupe are chosen. This service and this choice are the object of all the care of the first woman.

A large green curtain with flowers separates the royal bed from the rest of the room. It is mounted on a platform, made of precious wood, and the gold embroidered fabric covering the mattress is in the color of the day*.

The king lives surrounded perpetually by his wives and dancers. At the foot of his bed, two of them are crouching, always present, day and night. One is swinging a light fan of feathers at the end of a long handle; the other is holding ready the fly swatter of frayed silk. Outside the stage, and spread out in the room, sitting on mats, bright as flowers and cheerful as children, the rest of the service keeps company with its master.

They smoke, chew betel and replace themselves with fans or fly swatters. From his bed, His Majesty speaks to them, and his eye caresses their faces. To please him, they put pleated 'sampot', perfumed with champa flowers. Their lively scarves embalm the sandalwood. They sing in chorus, and the musicians accompany them. The King beats the measure with his hands, if he is happy and unoccupied; and everyone is very happy.

By the large bays open on the gardens, the nights quickly become overwhelming. Lamps light up and shout at each other with the smoke of the cigarettes. The fan on the King's forehead beats faster in the dancer's attentive hands, because the evenings are heavy. Then, suddenly, the orchestra breaks up; the suspended voices die one by one; all that can be heard is the discreet sound of betel boxes bumping into each other, imperceptible whispers, sometimes the distant bell of a Chinese street vendor, a croaking of crows... The King is sleeping...

Although he always has his dancers in his company, the King never makes them dance for him alone. If he is sad, he makes them sing, or play the musicians."

* At court, the "sampot", the costumes, are subject to a color that changes every day: Sunday, red; Monday, light yellow; Tuesday, green; Wednesday, purple; Thursday, dark blue; Friday, light blue; Saturday, black. Depending on whether a ballet takes place on one of these days, the actresses' sampot have the corresponding color.

About the freedom of royal dancers

In our page dedicated to the King Norodom's actresses and dancers, we have seen how they were recruited and deprived of freedom. Under the reign of King Sisowath, they have a little more freedom. G. Groslier writes: "More debonair (than H. M. Norodom), H. M. Sisowath let things go better. He even grants permissions of several days. But the thousand sharp eyes of jealousy and intrigue await the outgoing woman."