Last update: December 5, 2023

Angkorian iconography is rich in characters in a dance position. There are two canonical positions: that of

the Apsara proper and that of the sacred dancers. Unfortunately, the popular literature, but also the scientific one, often confuse each other. This article aims to clarify the

subject.

Note: In the singular, the Sanskrit script of the term apsara is apsarás. As for the plural, it becomes

apsarasas. However for practical reasons, we will use the spelling "apsara" in the singular and "apsaras" in the plural.

Apsaras through Angkorian epigraphy and iconography

According to the sources of classical India, the apsaras are in finite numbers, from seven to twenty-six, each with a

name and a specific function. However, many variants exist. Some writings also evoke thousands of apsaras. Old Khmer epigraphy quotes temple maids named after some apsaras (Tilottamā,

Urvaśi, Manovatī, Menukā, Rambhā, Sānamatī).

Various texts from classical India describe the origin of the apsaras. Here is a summary:

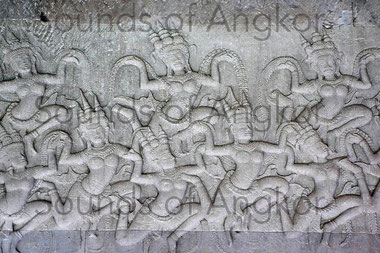

“At the beginning of time, deva (gods) and asura (demons) were all mortal and struggled for the mastery of the world. The weakened and vanquished gods asked Vishnu's help, who proposed that they join forces with the demons to extract Amrita, Kshirodadhi's nectar of immortality, the Milk Ocean. To do this, they had to throw magical herbs into the sea, overthrow Mount Mandara so as to put its top on the carapace of the tortoise Akûpâra, an avatar of Vishnu, and use the serpent Vâsuki, the king of the Nagas, to put the mountain in rotation by pulling alternately. After a thousand years of effort, the churning produced a number of extraordinary objects and wonderful beings including the apsaras”.

This text is illustrated by the long bas-relief of the east gallery, south wing, of the temple of Angkor Wat. The apsaras of this scene bring us the irrefutable proof of the Khmer representative canon. It should be noted, however, that while most of the apsaras in this scene are female, males are also represented.

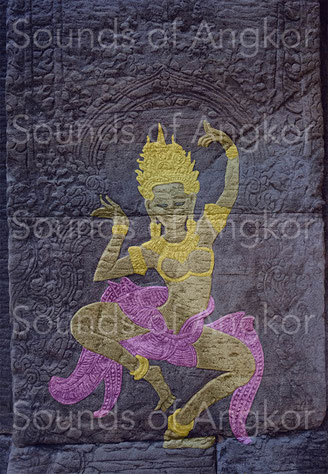

The apsaras of this scene above bring us the irrefutable proof of the Khmer representative canon. It should be noted, however, that while most of the apsaras in this scene are female, males are also represented. This remark was made for the first time by Phalika Ngin. But even outside this bas-relief witness, their representation always responds to the same canon:

- They (male or female) are represented in the heavens, always above the divinities or the king, himself of divine essence. In Phnom Bakheng temple for example, all of them are male.

- They float in the heavens in a characteristic position, that is to say with one leg raised backwards.

While the churning of the Milk Ocean is a recurring iconographic theme in Khmer temples, the mention of apsaras is quite rare in Khmer epigraphy, despite the 1360 inscriptions recorded to date (2018). Even if the texts of classical India were known by the ancient Khmer, it is necessary to understand what was their vision of the apsaras. Following are some translations from Sanskrit epigraphy by the École française d’Extrême Orient in various BEFEO (Bulletin de l’École française d’Extrême Orient).

« Comme le soleil (salué) par les Siddha, par les troupes des apsaras, par les plus parfaits brâhmanes et par les Kinnara, il était sans cesse adoré par les plus puissants rois (dont le front) reluit de l'éclatante rougeur de la poudre de ses pieds; - et bien qu'apparu à Svargadvârapura [ou: sorti d'une ville qui était la porte du ciel], il illuminait le séjour suprême des créatures ... ayant distribué cent linga sur la surface de la terre. »

Translation: "Like the sun (greeted) by the Siddha, by the apsara troops, by the most perfect Brâhmans, and by the Kinnara, he was unceasingly adored by the most powerful kings (whose foreheads) shone with the bright red powder of his feet; and though he appeared in Svargadvârapura [or: came out of a city that was the gate of heaven], he illuminated the supreme dwelling of the creatures ... having distributed a hundred linga on the surface of the earth."

This text confirms the multiplicity of apsaras represented in Khmer iconography.

« Voyant son propre corps à la place qui lui convenait, déchiré par l'épée gluante abaissée par la main de ce roi, l'âme interne de l'ennemi mort, par crainte de s'enfuir, s'entoura vite d'apsaras. » (BEFEO - IC I, LXXXVII p.87 - Stele of Prè Rup.)

Translation: "Seeing his own body in its proper place, torn apart by the slimy sword lowered by the hand of this king, the inner soul of the dead enemy, fearing to flee, soon surrounded himself with apsaras."

The Sanskrit term of the original text (Stele of Prè Rup) translated by "âme interne/internal soul" by G. Cœdès is ntarātmān. As absolute consciousness or pure consciousness, the ātman is also the Brahmin in the Vedānta and especially the Advaita Vedānta. The nature of ātman is identical to that of the Brahmin, namely: to be absolute and eternal, absolute consciousness, pure "I Am This" ("This" means the Universal Soul, Brahmin, which is the power that invades all, everything and every creature) and absolute bliss. (Translation from the Dictionnaire de la Sagesse orientale - Bouquins Collection - Editions Robert Laffont 1989)

Apsaras appear here as protective beings of the vital energy that escapes from the body when passing from life to death.

« Bien que dans le combat il ne fût doué ni de libéralité, ni de patience et autres vertus semblables, ce roi vertueux donnait aux héros (ennemis) abattus la foule des apsaras et des lotus. » (BEFEO - IC V p.102. Stele of Prasat Ben Vien – K. 872 - 10e century)

Translation: "Although in battle he was gifted neither with liberality nor patience and other similar virtues, this virtuous king gave the slaughtered (enemy) heroes (enemies) apsaras and lotuses."

As in the previous example, the king offers apsaras to his fallen enemies to preserve their vital energy. Perhaps without the apsaras, the vital energy could turn into a vengeful energy sowing disease and death. Unless it is respect, even compassion for his enemis.

« Le bâton de son bras, répandant ses dons sur les brâhmanes et les autres (castes), resplendissait, par suite de l'offrande qu'il avait faite de la multitude de ses arrogants ennemis aux femmes célestes qui prenaient leur plaisir avec eux. » (BEFEO IC V p.102. Stele of Tuol Ta Pec – K. 834, 10e century, XXVIII)

Translation: "The staff of his arm, pouring out his gifts on the Brâhmans and others (castes), shone forth as a result of the offering he had made from the multitude of his arrogant enemies to the heavenly women who took their pleasure with them."

The term apsara is not directly quoted by the text but an equivalent seems to refer to it. It is clear here that the apsaras offer themselves to fallen men. This belief was likely to motivate the soldiers to fight.

From Brahmanism to Buddhism

Breaking with the Brahmanic religion of his predecessors, while continuing to allocate the service of the Brahmins in its temples, the Royal Triad (consisting of King Jayavarman VII and his two spouses, queens Jayarajadevi and Indradevi, according to the research by Phalika Ngin and Gérard Maitrepierre) was the first power's entity to impose Buddhism as a state religion. This Buddhism is considered as Mahayanic by the most of scholars, sometimes tantric, but we prefer to call it "Buddhism of the Royal Triad" as it is singular and marked by the personality of these sovereigns who have represented the main Buddha of Bayon temple under the features of Jayavarman VII himself.

The Royal Triad has preserved, on the religious level, many references to Hinduism and in particular, as far as we are concerned here, the dance as a tool of communication with the deities.

Sacred dancers through epigraphy

By "sacred dancers" we mean the servants of Hindu or Buddhist temples (during the reign of the Royal Triad) whose role was to dance for the deities. They are mentioned in epigraphy under the name of nāṭikāḥ in Sanskrit and rmāṃ, rmmāṃ or ramaṃ in Old Khmer. There are other terms for lay dancers, but this doesn't apply to this article. Pre-Angkorian texts in Old Khmer also mention the term pedānātaka rpam (Kok Roka inscription —7th-8-th century— BEFEO IC V, K. 155. P.65: 9) to describe groups of dancers (ballet); nātaka means "actor" and rpam "dance". As for the term pedā, its meaning is uncertain. But the Sanskrit word peṭaka means "multitude, company, group". Pedānātaka rpam allows us to understand that what we call "dance" should rather be understood as "global theater". Indeed, sacred dance is not strictly speaking a spectacle, even if it is given to entertain the gods; however the aesthetic flatters the human senses that look at it. Sacred dancers perform, through their body movements, narrative dances that is to say a choreographic corpus that can replace the words and syntax of a text to describe a situation or tell a story. Religious dance is, like the verb, a tool of communication with the deities. The gesture (hands -mudrā / litt "seal" -, general movement of the body strictly speaking, eyes, head ...) replaces the words. In the South Indian tradition, mudrās strengthen the sacred word (mantra) or mental intention (bhavana) when it exists.

The term pedānātaka rpam demonstrates that the sacred dancers also evolve in groups, which is confirmed by the iconography.

Physically, the sacred dancers represent offerings made to the temples by donors. A pre-angkorian text in Old Khmer, referenced K. 51, mentions that a man named Mratan Indradatta offered ten dancers (rapam) to the temple. What the text doesn't specify is whether these maids were already trained or not. We don't know anything about their age. On the other hand, we know the names of four of them, the others being ruined.

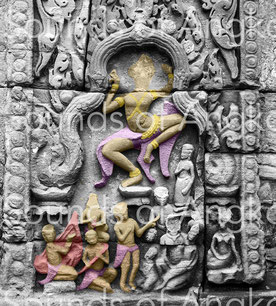

Sacred dancers through iconography

Sacred dancers are widely represented in Angkorian iconography. The question now is whether these sculptures represent sacred dancers operating in temples or mythological characters.

A large number of these dancing characters are represented in the "halls to the dancers" (that are halls in which female

dancers are represented, but not halls exclusively dedicated to the dance) of three temples built under the reign of the Royal Triad (Bayon, Preah Khan and Banteay Kdei) and in

the first gallery of Angkor Wat facing west that could also be called "the dancers' gallery".

Let's take a closer look at how these characters are represented:

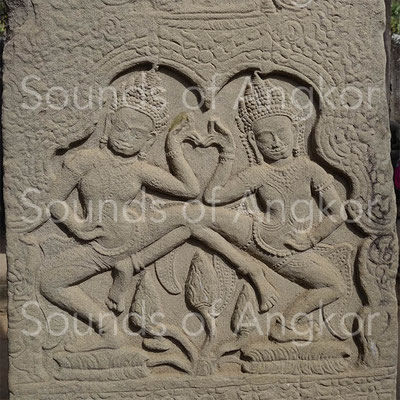

- In Bayon, the majority of the dancers are represented on the pillars of the eight cruciform pavilions of the main and intermediate directions; they are alone, by two in mirror or by three (a large figure in the upper register and two smaller ones in the lower register in mirror). Other solo dancers are engraved on all or part of the four faces of the inner pillars of the outer gallery. Still others find place at the foot of pillars in various parts of the temple.

- In Preah Khan, high relief friezes represent dancers in symmetry around a larger central dancer. The pillars of the dance hall are engraved with dancers' duets.

- In Banteay Kdei, the pillars of the dance hall are engraved with dancers' duets.

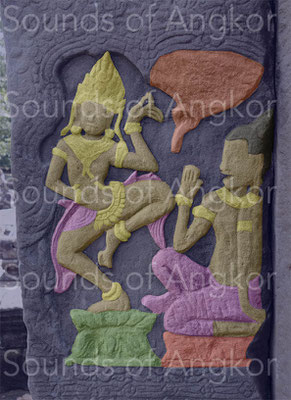

Until now, there is no evidence that characters originally defined as "sacred dancers" are not mythological characters. To prove it, there is a complementary iconography that we call here "female dance masters". In Bayon and Banteay Kdei, they are engraved in strategic places:

- In Bayon, on most of the entrance pilasters of the eight cruciform pavilions mentioned above. Other types of representations, rare, are also visible: a harpist alone, a harpist with a singer, and three dancers getting ready.

- In Banteay Kdei, on the inner and outer pilasters of the hall to the dancers' doors; they are represented either alone, facing a dancer in action, or in a high position compared to a dancer sitting on the floor.

An image of Bayon (right) has aroused our attention. It shows a sitting female dancer, looking herself in a mirror. She is dressed by a woman whose maturity is recognizable by her sagging

breasts.

Another one, in Banteay Kdei (left), shows a dancer preparing herself. In front of her, a box containing perhaps utensils or jewels.

One thing is certain: all these images show real characters.

In Preah Khan, a scene seems to summarize the role of the sacred dancers. Bottom right, a family with parents, children and perhaps grandmother (?). Bottom left, a string orchestra, consisting of a harpist, a zither player, a cymbals player and a singer. Above, a sacred dancer in a standardized position communicating with deities.

The position of the sacred dancers corresponds to a constant canon in the 12th and 13th centuries. One foot is placed on the ground, another raised, legs bent, two arms up or an arm up and one down. It is not only a canon of representation, but also a sample of the real positions of religious narrative dances.

In conclusion

These daily scenes and these established relationships of dance teachers with their pupil, always current in the artistic environment of contemporary Cambodia, cannot describe mythological scenes, any more than apsaras. Apsaras and sacred dancers cannot be confused. The first ones belong to Hindu mythology and found an iconographic continuum in the Buddhist temples of the Royal Triad. The apsaras find their place in the heavens and are thus represented above the king or deities in the iconography. Angkorian Sanskrit texts evoke their direct role in the celestial world, that of welcoming and maintaining the integrity of vital energy at the moment of death, or of offering themselves to fallen warriors.