Last update: December 5, 2023

Introduction

At Angkor Wat, dance takes on multiple forms. Khmer artists have devised specific codes to represent each form, making it easily understandable at a glance. In this section, we showcase various styles of dance.

- Celestial dance of the apsaras

- Celestial warrior dance

- Martial dance

- Sacred dance

- Sacred fire procession dance

- Dance for secular celebrations

- Shiva's cosmic dance

Celestial dance of the apsaras

Beyond its gigantism, Angkor Wat is famous for its huge bas-relief dedicated to the Churning of the Ocean of Milk (third gallery, east side, south wing), which gave birth to, among others, the celestial dancers apsaras*.

*The Sanskrit transliteration of apsara in the singular is apsarás. In the plural, it becomes apsarasas. For practical reasons, we'll use the more common spelling "apsara" in the singular and "apsaras" in the plural.

According to classical Indian sources, there are a finite number of apsaras, from seven to twenty-six, each with a specific name and function. However, many variations exist. Some writings also mention thousands of apsaras. Old Khmer epigraphy (K. 327) cites temple maids with apsara names (Tilottamā, Urvaśi, Manovatī, Menukā, Rambhā, Sānamatī).

Various texts from classical India describe the origin of apsaras. Here's a summary: "At the dawn of time, the deva (gods) and the asura (demons) were all mortal, struggling for mastery of the world. The gods, weakened and defeated, sought the assistance of Vishnu, who suggested they join forces with the demons to extract amrita, the nectar of immortality, from Kshirodadhî, the ocean of milk. To do this, they had to throw magic herbs into the sea, overturn Mount Mandara so as to place its summit on the shell of the turtle Akûpâra, an avatar of Vishnu, and use the snake Vâsuki, king of the Nâgas, to rotate the mountain by alternately pulling on it. After a thousand years of effort, the churning produced a number of extraordinary objects and wonderful beings, including the apsaras". This text is illustrated by the long bas-relief in the third gallery, east side, south wing, of Angkor Wat. The apsaras in this scene provide irrefutable proof of the Khmer representative canon:

- One leg bent and the other raised backwards

- Bust arched back

- Both arms in the air, holding jasmine garlands

- They are always depicted in the heavens, above the king when he is present, and above or at the same level as the deities (in this case, Vishnu).

It should be noted, however, that while most of the apsaras in this scene are female, males are also represented.

Note that the upper part of the sampot សំពត់, the traditional dress, is corolla-shaped. In the many medallions adorning the door jambs at Angkor Wat, apsaras are depicted without legs. They can be recognized by this corolla.

To find out more about the role of apsaras, click here.

Celestial warrior dance

Hundreds of images of celestial warriors adorn the temple walls. The finest representations can be found on the fourth enclosure, on the outer east side. The first celestial warriors on horseback appeared around the 9th century, emerging from the floral scrolls of the temples' ornamental foliage. At Angkor Wat, these figures ride real or hybrid animals. Their stance is one of both dance and combat, with no truly definable boundaries. This issue is also recurrent in the battle scenes from the Battle of Kurukshetra (next paragraph).

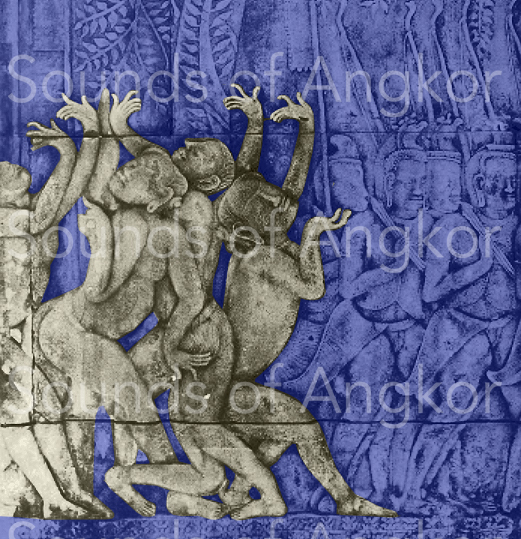

Martial dance

Martial dances have probably existed as long as men have been at war with each other. Some of them still exist in Southeast Asia, notably among the Toraja of Sulawesi (Indonesia) and the Nghe of Laos, where we were able to film them.

Numerous examples flourish at Angkor Wat, both in the large bas-reliefs in the third gallery and on the door jambs. Dance movements blend in with the warriors' fighting stances, so it's not easy to tell the difference. Some positions are reminiscent of those of the celestial warriors, the subject of the previous chapter.

In the bas-relief of the Kurukshetra War (third gallery, west side, south wing), the sculptors have brilliantly depicted beautiful attack positions in which the position of the legs is similar to that of sacred dancers, displaying a certain pre-eminence over the enemy. One example shows warriors advancing synchronously with shields and spears. The desire to impress the enemy is always perceptible.

Sacred dance

We call "sacred dance" the dances performed by the "sacred dancers", whose role was to entertain the Hindu gods at the time of Angkor Wat. The dance was considered an offering. We know both the Sanskrit term, nāṭikāḥ, and in 10th-century Old Khmer, rmāṃ or rmmāṃ, to designate the sacred dancers. We also know the term rnaṃ, in the 11th c., to designate this precise dance form. We don't know exactly where in the temple these dancers performed. In the 12th century, the term kralā rāṃ refers to the "dance hall". However, in view of the sculpted and sometimes colorized decorations, we can assume that sacred dancers performed in the various sanctuaries of the fourth (west) gallery, since we can see representations of both sacred dancers and dancing masters, in the cruciform cloister and in the central tower (bakan).

There's no hidden meaning to the position of the sacred dancers, just a formal canon. In the fourth gallery, the long frieze of dancers shows three positions, two of which are mirrored. The video below is an animation of these positions; it does not reflect the reality of sacred dance. To find out more, click here.

Animation of the dancers represented along the entire length of the fourth west gallery.

Sacred fire procession dance

In the "Orchestras from the 7th to the 16th century" section of this site, we mentioned King Suryavarman II's parade orchestra, accompanying the Sacred Fire procession (Historical Parade in the third gallery, south side, west wing). Now preceded by two dancers, this is one of the few places in Angkor Wat where a bas-relief has been deliberately destroyed. In place of this insult, there were once three other dancers, making this one of the most extraordinary dance scenes in the Angkorian world. Thanks to a document from the École française d'Extrême-Orient (EFEO), we've been able to reconstruct the scene of the five dancers and, in the process, have probably discovered the probable reason for their destruction. Indeed, the position of the dancer and the incompleteness of the sculpture may suggest that his posterior is uncovered, which may have prompted the shooter to destroy this masterpiece. The number of five dancers is not insignificant, as much of the architectural numerology at Angkor is based on this number.

Here, we are in the presence of several ancient elements that find continuity in the present day:

- The Sacred Fire offering

- Brahmins

- An orchestra of trumpets, conches, drums and cymbals

- Dancers, including a singer-dancer.

During the Buddhist kathina (or kathen កឋិន) festivities, the faithful offer the monks monastic robes (sbang), everyday objects and a meal. The faithful arrive in procession at the Buddhist monastery (wat វត្ត) and make three rounds of the temple proper (vihear វិហារ) in a clockwise (dextrogyratory) direction, the direction of the sun's course in the northern hemisphere and of life, preceded by an orchestra and dancing girls. In the case of Angkor Wat, the temple-mausoleum of King Suryavarman II, the procession is counter-clockwise (senestrogyre), linked to death. By comparison with the ritual ingredients of Angkor Wat, we recognize, within the framework of the kathina festivities:

- Offerings of robes and other utilitarian objects for the monks

- Monks

- An orchestra consisting of a gong, drums, cymbals and a two-stringed hurdy-gurdy

- Female dancers (or transvestite or transgender men) performing dance movements comparable to those on the bas-reliefs.

This procession is unique in Angkorian iconography, and the kathina festivals offer a direct link with it. Once again, Cambodia proves its ability to maintain its traditions - a kind of continuity in change!

The hand movements depicted in this bas-relief seem similar to those of the popular roam vong រាំវង់ dance with, here too, a turning of the bodies.

Dance for secular celebrations

Profane celebratory dances (or at least those considered so by ourselves) are rare in Khmer iconography. Sculptors have depicted a variety of movements that cannot be identified with other forms of dance. On the other hand, there are thousands of dancers in the Angkor Wat pedestals, but we can't yet classify them.

In the south-west corner pavilion of Angkor Wat's third gallery is a large scene that ranks among the finest in Khmer sculpture. It shows figures drinking rice beer, women looking after children, young girls embracing, a cockfight and many other scenes above those published here. The scenes take place on a boat driven by paddlers, whose bow depicts a Garuda head.

To the left of the panel, three dancers wear long, rich garments adorned with chan flowers, held at the waist by a belt. The position of the heads, legs and arms are distinct, offering a kind of representation of chaos. The dancer on the left plays cymbals. The dancer in the middle has a wiggle; his folded arms and legs seem to be mirrored. The dancer on the right looks up with his left arm opposite his gaze. This scene deliberately breaks with the canonical, orderly positions of apsaras, sacred dancers and martial artists.

These three positions resemble certain movements in Ukrainian kazatchok dance!

The scene above belongs to a pedestal in the south gallery of the cruciform cloister. It appears to be a country scene. A dancer is confidently performing a secular dance. She is accompanied, on the far right, by a flautist playing with one hand and, on her left, a cymbal player. This is one of the few scenes in Angkor Wat where identifiable musical instruments are used to animate a dance. The dancer's attire, hairstyle and arm position are unlike anything else we know. The figure on the left, with his index finger pointing, is probably a singer.

Shiva's cosmic dance

The cosmic dances of Shiva are numerous in the sculpture of Angkor Wat, notably on the door jambs. In Sanskrit, this dance was called aticaṇḍataṇḍavayutam. We don't know the equivalent in Old Khmer. At Angkor Wat, dancing Shiva is depicted in isolation or surrounded by Kāraikkāl Ammaiyār, Vishnu, Brahma and Ganesha.

For more information and iconography, see our page: The ancient musical instruments through Shiva's dances.