Last update: December 5, 2023

The two-stringed fretted zither is currently the most unlikely of all reconstructed Angkorian musical instruments. What has led to this hypothesis is that some of the sculptures show musicians with playing positions different from those of the standard double-resonator zither.

What sets it apart:

- The upper resonator is not supported on the chest, but placed on or above the shoulder.

- The instrument is longer.

- Both hands are represented in the center of the instrument, which means that the right hand cannot generate partials as on the "standard" double-resonator zither.

This is why we believe that two different zithers existed simultaneously in the Angkorian period: one without frets (also called "double-resonator zither" by us) and another with high frets.

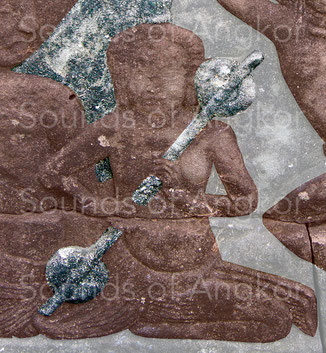

Photos 1 and 2 show the same type of zither, one seen from the front, the other in profile. On the latter, the lower part of the body is raised. This is where the string is attached. Also visible at the top of the instrument is what appears to be a tuning peg. Note that, despite the minimalism of the depiction, the sculptor has depicted this detail.

If we take into account the length of the instrument, the anchoring point of the resonators, the playing position in which the upper resonator does not rest on the musician's chest, and the hands close to the center rather than at either end, we can then hypothesize that these instruments had keys or frets.

This zither could be the ancestor of the krapeu zither.

The fretted zither appeared in India around the 10th century (3-4). During this period, harps and lutes gradually disappeared, leaving the way clear for the development of a variety of stick and tube zithers.

If we compare the iconography of ancient Indian fretted zithers, it is clear that the position of the right hand differs, as it is no longer necessary to generate partials on the string, but simply to vibrate the required length of string.

Another single-resonator zither has been continuously perpetuated by minority ethnic groups on the borders of Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam. It has two strings, one for melody, the other for accompaniment, a calabash resonator and truncated cone-shaped keys made of carved wood or kapok thorns with the tips cut off. Some of these instruments are fitted with a device that gives the sound an aesthetically pleasing stridency and lengthens the resonance time. A small piece of wire or a thin bamboo strip is inserted between the string and the bridge. This device already existed on the single-string zithers of ancient India.

Another system consists of a rectangular piece of ivory or deer horn of varying thickness and convex curvature. It appears as early as the 6th century in pre-Angkorian iconography. Numerous iconographic testimonies attest to its durability over the centuries, and musical treatises describe this element. In particular, it can be found on the bichord zithers of the Êdê and J'rai peoples of Vietnam.

We have included the strident sound device in the reconstruction of our fretted zither. It also exists on the krapeu zither.

Monochord ekatantri zither from 10th c. India. Note the resonator at the top of the instrument, the small, elongated piece across the base of the string that generates an aesthetically pleasing stridency and lengthens the duration of the sound. Also visible on the left hand is a stick that the musician slides along the string as a substitute for digital playing. We also note the characteristic position of the right hand playing on the string's partials. Many of these details are absent from Khmer sculpture.

If we compare Angkorian iconography with contemporary playing positions, we can see that there is no standard way of positioning instruments. There are as many habits as there are musicians. A great richness and immense freedom in our standardized world!