Last update: December 5, 2023

Documentary

French ethnomusicologist and archaeomusicologist Patrick Kersalé has been crisscrossing Asia for more than 30 years, in search of ancient instruments and music. In 2012, he undertook to study and reconstruct the ancient musical instruments of Cambodia, between the 7th and 16th centuries: harps, zithers, cymbals, drums, trumpets, conches and oboes were thus brought back to life!

This film from 2012 is a state of the art. We are now in 2021 and the project continues to develop.

Genesis, by Patrick Kersalé

The story of my passion for ancient musical instruments began in 1984 in Paris while I was playing the Romanian pan flute nai. It began when I met the music therapist Patrice Barret who had just finished his thesis on the pan flutes of the world. His document fascinated me and I decided to study the subject further. At the time I was working on the Avenue des Champs-Elysées in Paris, not far from the Musée de l'Homme. It was the time of the Minitel, the Internet was non-existent. At lunch time, instead of going to the canteen, I went to the library of the Musée de l'Homme to do some research on panpipes. At the same time, I began researching the collection of pan flutes in the CNRS ethnomusicology laboratory, and then made facsimiles, thus creating a unique collection that would be exhibited for several months at the Châtelet - les Halles RER station in Paris.

In 1991, I went to Indonesia, then to the heart of the primary forest in Central Africa, among the Aka Pygmies. The story continues in parallel in West Africa, Southeast Asia, especially in northern Vietnam, to collect the music of ethnic minorities, the dances of possession of the Kinh or the song of professional singers of ca trù which will be listed by UNESCO in 2009 on the List of Intangible Heritage requiring urgent safeguarding.

In February 1998, I made my first trip to Angkor. I then took the measure of the richness of the musical iconography in the ancient Khmer temples. At the same time, I developed an important pedagogical project on world music for the French National Education system with the Éditions Lugdivine, which lasted ten years.

In 2006, I left for a six-month trip to Asia to film in High Definition the music recorded during the previous years. In August 2012, I moved to Phnom Penh with my family; this is where the study and reconstruction of the musical instrumentarium of the ancient Khmers began. In 2021, I am still in Cambodia …

Approach

The project to reconstruct the musical instruments of the ancient Khmers is based on field experience acquired since the early 1990s. At the beginning, like any researcher, I compiled books and articles related to the life of the ancient Khmers and the Angkorian instruments. Unfortunately, I noticed that no archaeomusicological literature is reliable because no real musicologist has worked on the topic. There are however some eminent figures among the scientific authors, but musicology is full of traps. I then decided to go back to the source, namely the iconography of the temples (bas-reliefs, high reliefs, frescoes), the texts in Sanskrit, in old Khmer and in Chinese, the objects resulting from the excavations.

This research involves hundreds of hours spent in temples throughout Cambodia, as well as dozens of hours in libraries looking at photographs of ancient iconography. It is also a work of comparison of Khmer iconography from the seventh to the sixteenth century, of Cham sculpture from Vietnam since the Chams are a Hinduized people who once shared the same musical instruments as the Khmers. It is also a crossing of Khmer and Cham sources with Indian and Javanese iconography, or the confrontation of iconography with the instruments that spread along the roads of Hinduism and Buddhism.

If the objective was to reconstitute each instrument, it was also to bring the orchestras back to life in order to understand their coherence and acoustic complexity.

But this project goes far beyond the reconstitution of ancient Khmer instruments, since the instruments of the Indianized/Hinduized Chams (Vietnam, iconography available between the 8th and 10th centuries) and the Indianized/Buddhized Javanese of the Borobudur period (9th century) are similar. Thus, any reconstruction made for the Khmer applies to these other two cultures. We agree that there were certainly local differentiations, but the statuary does not present any relevant details to judge this. This project will lead me to travel in several Asian countries: Cambodia, Vietnam, Laos, Thailand, Myanmar, Nepal, India, Singapore, Japan, France in order to meet instrument makers, musicians, to understand ancient musical practices, religious facts and to visit museums.

Project timeline

1991 - 2012

- Study of musical instruments from Southeast Asia, India and Nepal, but also from West Africa, European prehistory and the French Middle Ages.

1998

- First contact with Angkorian iconography.

2009 - 2020

- Study of pre-Angkorian, Angkorian and post-Angkorian instruments, based on iconography, epigraphy, ethnography and archaeological objects.

- Conferences, exhibitions, publications.

2012 - 2020

- Experimental reconstructions of ancient Khmer instruments based on research data.

- Creation of the Sounds of Angkor band.

- Acoustic and functional tests of the instruments by the Sounds of Angkor band.

- Technical and acoustic assessment and organological adjustments.

2016 - 2021

- Permanent exhibition at Theam's Gallery (Siem Reap).

- Proposals for aesthetic arrangements of the instruments.

Revival of the instruments

Since 2012, Sounds of Angkor has become an important part of the Cambodian cultural landscape, notably with its first exhibition at the French Institute of Cambodia (Phnom Penh), visited by the Royal Court of Cambodia, by numerous researchers and government officials, by hundreds of Cambodians proud to rediscover a part of their vanished culture and even by the Director of Communications of the Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. In this intellectual process, the reconstitution of the musical instruments visible - or not - on the bas-reliefs is obvious. Almost all of the instruments represented between the 7th and 13tth centuries are of Indian origin, even if they were gradually Khmerized. Our mission consisted in making "reconstruction proposals", knowing that we have no real object for the instruments made of organic material and that our knowledge is mainly derived from the iconography of ancient Khmer temples and from contemporary ethnography.

On the technical level, we have encountered few constraints other than the availability of certain materials and the legal framework surrounding some of them. The wood species commonly used in the making of traditional Khmer instruments were easily found. On the other hand, some materials of animal origin were missing. We do not know the exact nature of all the materials used in the past, but we know from ethnography and some ancient instruments preserved in museums, that deer skins were used for the membranes of drums or that elephant ivory was used in the manufacture of some cordophones.

Given the low level of detail in Khmer iconography, in the first phase of the project we restricted the decoration of the instruments to the friezes of lotus flowers bordering the skin of the large drums and visible on certain reliefs. When we used lacquer or gold leaf, it was only in a modern, deliberate and assumed artistic gesture.

We allowed ourselves to use electrical machines in order to accelerate the manufacturing process: chainsaws, band and circular saws, wood lathes, drills, sanders... We naturally asked ourselves the question of the tools used in the Angkorian period. There are few bas-reliefs showing tools. We will retain, for the most part, the axe and the cutter for woodworking. We know, however, by observing the traces left in the stone and the Angkorian achievements, that the ancient Khmers possessed the same traditional tools as contemporary woodcarvers. In particular, they knew the foot or hand lathe. Contemporary ethnography still offers a few examples.

Partnerships

During this time of research, we have established informal partnerships with numerous partners. Click here for a complete list.

Reconstructed instruments

We know nothing of a possible classificatory approach to Angkorian musical instruments other than the Sanskrit stele of Wat Prah Einkosei* (early 11th c.) mentioning several instrument names classified by typology, (with a few rare exceptions in order to preserve the poetics of Sanskrit). In a chapter of the Nātya-shāstra, musical instruments are classified into four categories according to morphological parameters underlying their mode of sound production: tata vādya, shūsirā vādya, avanaddha vādya, ghana vādya.

Below is a list of the instruments reconstructed according to this classification, along with their names when known and the date of the iconography, in parentheses.

Abbreviations for the dating of the name: Kh.11th / Old Khmer language of the 11th century; p.a. (pre-Angkorian) / Pre-Angkorian Khmer language; Sk. / Sanskrit.

*(Cœdès G. 1952 – K.263, IC IV, p.124, VIII)

tata vādya

Stick zither with a single resonator - kañjaṅ, kañjoṅ p.a. - (7th c.)

Double-resonator zither - vīṇā Sk. ; kinnara Kh.9-11th - (12th-13th c.)

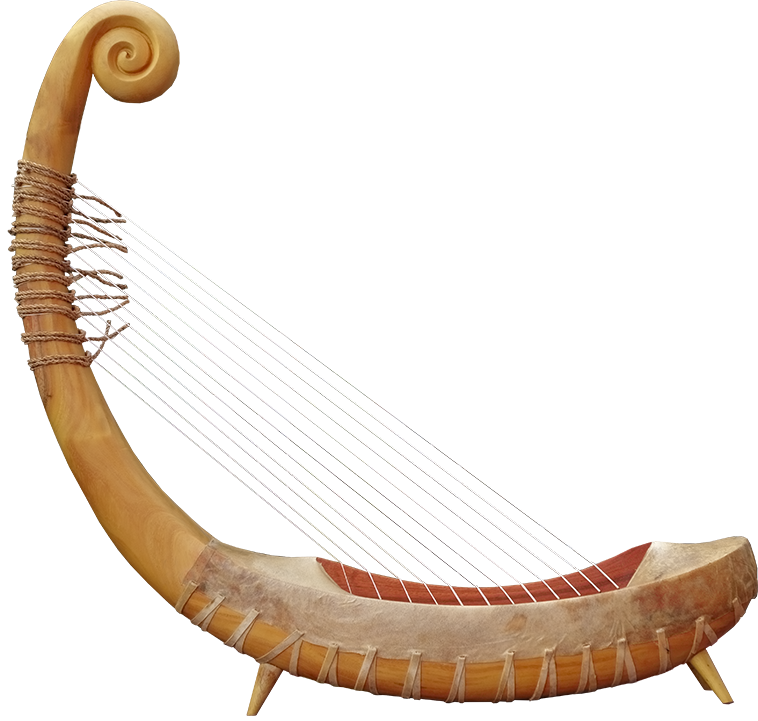

Angkorian harp - viṇā p.a. - (7th c.)

Garuda's head harp - viṇā p.a. - (12th-13th c.)

Post-Angkorian harp - viṇā p.a. - (12th-13th c.)

Lute - trisarī Kh.9th - (9th c.)

shūsirā vādya

Conch shells - śaṅkha Sk. Kh.9-12th - (12th-13th c.)

Conch shell with frame - śaṅkha Sk. Kh.9-12th - (early 12th c.)

Terracotta conch shell - śaṅkha Sk. Kh.9-12th - (Angkorian)

Horn (or olifant) (buffalo horn)

Flute with end mouthpiece - kluy Kh.10th - (12th-16th c.)

Transverse flute - veṇu p.a. - (7th c.)

Oboe with calabash pirouette - (12th-16th c.)

Bamboo trumpet - (12th-16th c.)

Metal horn (short) - tūrya, tūryya Kh.10th - (12th c.)

Metal horn (long) - tūrya, tūryya Kh.10th - (12th c.)

avanaddha vādya

Cylindrical drum - (12th c.)

Terracotta goblet drum - (12th-13th c.)

Wooden goblet drum - (12th-13th c.)

Simple hourglass drum - thimila Sk. - (7th c.)

Hourglass drum with nāga-shaped holder and bells - thimila Sk. - (12th-13th c.)

Barrel drum - (7th c.)

Barrel drum (oblong) - (11th c.)

Barrel drum with stand - (16th c.)

Rattle drum - ḍamaru, ḍamarin Sk. - (Angkorian)

ghana vādya

Bell tree - (12th-13th c.)

Elephant bell of closed - ghaṇṭā Sk. - (12th-13th c.)

Vajra bell - ghaṇṭā Sk. - (12th c.)

Horse bells of closed - (12th-13th c.)

Large cymbals - cheṇ Kh.10th - (11th-13th c.)

Small cymbals - cheṇ Kh.10th - (7th-16th c.)

Bossed gong (couple) - (16th c.)

Elephant bell of open - (11th-13th c.)

Scraper - (12th-13th c.)

Zithers

Zithers are of primary importance in the string music of pre-Angkorian and Angkorian Khmer orchestras. Iconography and epigraphy provide little knowledge of their construction. An instrument called śikharā appears in the inscriptions of Lolei (9th c.); it could be a zither, but no iconography represents it. No reconstruction is therefore proposed.

Stick zither with a single resonator

The stick zither with a single resonator is attested as early as the 7th century on three sculptures: a lintel from Sambor Prei Kuk preserved in the National Museum of Cambodia, a high relief from Phnom Chisor (11th c.) and a bas-relief from the third enclosure, north gallery, east wing, of Angkor Wat (16th c.). It is also represented at Borobudur, Java (9th c.). The sculpture is of course silent as to the materials. The inscription of Prasat Komphus (late 7th c.) tells us that the temple received nine zithers made of a copper alloy metal and one with a gold coating. Given the lack of precision in ancient iconography and epigraphy, we have conformed to what we know best, the Khmer kse diev monochord zither, stripping it of the technological contributions of the 21st century.

For the neck, we used a precious wood called kranhung (ក្រញុង), of the genus Dalbergia, the densest and most valuable species in Cambodia.

There are two types of resonators: calabash, the only one used in Cambodia, and coconut, which is preferred in Thailand. The calabash, of the genus Lagenaria, is a creeping herbaceous plant of the Curcurbitaceae family. Information published by French ethnomusicologist Jacques Brunet in the 1960s reports that it grew naturally in the Cardamom forest (ជួរ ភ្នំក្រវាញ, Chuor Phnom Kravanh).

There are various shapes but it is probably the piriform fruits that made up the resonators of the zither. If we refer to current practices, the calabashes are dried, cut to size, hollowed out, and sometimes decorated by engraving before being fixed to the neck. In our reconstruction program, whether for this instrument or for the double resonator monochord zither (hereafter), we were faced with a challenge: sourcing calabashes. This cucurbit is only cultivated in Cambodia by the kse diev zither makers and everyone keeps their plantations and their fruits as a treasure. Some farmers cultivate it as food. For use in musical instrument making, it was necessary to cultivate a large number of them in the hope of collecting some of good size, shape and thickness. In Siem Reap, Thean Nga and his father created an arbour on which to climb the calabash stems so that the fruit would not touch the ground. Thanks to their meticulousness, beautiful specimens could be harvested.

The material of the rope is unknown to us, but if we refer to ethnology, we find it in vegetable fiber. However, we cannot exclude the use of gut and silk. As for metal, the most appropriate material to obtain a clear and powerful sound, we do not know if there were, in ancient times, metal strings thin enough to sound and strong enough to withstand the tension. We have conducted tests with silk strings of different diameters on a contemporary kse diev zither. There is no more difficulty in generating sounds than with a metal string, but the sound lacks clarity, resonance and power, which leads us to believe that musicians used metal strings, perhaps brass, as is still the case today in Cambodia.

Lessons from the reconstructions

- Neck. To the extent of its availability, we used kranhung ក្រញុង wood, the densest and most valuable species in Cambodia. The acoustic conductivity is optimal due to its density.

- Terminal piece, nāga-head shaped. On contemporary Khmer kse diev monochord zither, this piece is made of buffalo horn, bone or wood (formerly elephant ivory).

- Connecting piece. Between the neck and the end piece is a copper or brass tube. We have preserved this technology, knowing that the Angkorian people knew how to shape metal tubes in copper or bronze.

- Peg. This piece of the kse diev is made according to the taste of the marker or the sponsor. We made it from kranhung wood, sometimes faced with pieces of cattle bone.

- Ligature of the resonator to the neck. Rattan fiber.

- General aesthetics. In the past, we know that this instrument was made with extreme care with precious materials.

- Fixing piece inside the resonator. Slice cut out of a coconut shell.

- Acoustics. The instrument is not very sonorous but fits perfectly into the string orchestra depicted on the two Sambor Prei Kuk's lintels. (See below chapter “Orchestral reconstruction”).

Double-resonator zither

In the 12th-13th centuries, all zithers are represented with two resonators. Only one occurrence among dozens (high relief of the Bayon) shows a single string. This is most likely the same instrument as the single-resonator zither to which a soundbox has been added, for acoustic and perhaps also symbolic reasons. In the iconography, the playing position of the two instruments is similar.

This zither was played in pairs in temples, at the royal court of Jayavarman VII and for ordinary entertainment alongside harps, scrapers and small cymbals.

Lessons from the reconstructions: similar to those described above.

Arched harps

As early as 2012, we decided to reconstruct three models of bowed harps. At that time, we know nothing about their technology. We then left for Myanmar where we met a Burmese harp (saùng-gauk စောင်းကောက်) maker as well as a harpist with whom we trained in the playing technique. We also visit the Karen of Myanmar and Thailand to learn about their technology and discover the diversity of their models, in total opposition to the Burmese harp which is now standardized by the government.

With this new experience, we establish with trial and error the design of several harps. We then met an instrument makers in Phnom Penh, Keo Sonan Kavei and Kranh Sela, to whom we submitted our drawings in 1:1 scale. We started making them by practicing copying two Karen harp models brought back from our trip. At that time, these makers made xylophones and gong chimes for pin peat ensembles. Then followed the first reconstructions of pre-Angkorian (7th century) and Angkorian (12th-13th century) harps.

Pre-Angkorian Harp

The oldest representations of harps appear in the 7th century on two lintels from Sambor Prei Kuk, now in the National Museum of Cambodia. Another is in the Pakse Museum (Laos, discovered on Laotian territory, which was once partly part of the Khmer Empire. For the reconstruction, we crossed these three sources with those of Champa, Borobudur (Java, 9th c.) and some Indian sources, with the exception of the one of the Pawāyā lintel, of which we were only made aware in 2018; we were then pleased to note that the reconstructed model was in conformity with that of Pawāyā!

Lessons from the reconstructions

- Soundbox and neck. The structure of the harp is the result of an assembly of two pieces given the fact that wood has become rare in Cambodia. It is possible that in the past the instrument was made from a single piece of wood. Jackfruit (genus Artocarpus), widely used in Khmer instrument making, offers good results in terms of aesthetics, acoustics and longevity. The color varies from lemon yellow at the time of cutting, to dark brown after a few years of aging.

- Feet. The first pre-Angkorian harp was made without feet. Then we made other models with four feet to stabilize it. The harps represented in the pre-Angkorian period show a da gamba playing or with the instrument carried in a shoulder strap. The grip of the harp without feet is pleasant but requires a stand to put it down when it is not used, like the Burmese harps.

- Tailpiece. Red wood. The denser the wood, the better the acoustic conductivity.

- Soundboard. Python or goat skin. Deer skin may have been used in the past. Python is strong but goat is fragile; both are susceptible to insect and rodent attack and are sensitive to moisture.

- Lacing of the soundboard skin. We were inspired by the technology of the last harp used in India (bin baja) for the attachment of the skin of the soundboard, that is to say a skin laced and not studded. For the binding, we used cowhide.

- Strings. Originally probably silk. We used nylon microfiber, which is stronger, cheaper and easier to work with. We tested both materials and got a similar sound result. The maximum number of strings for a good acoustic performance is eleven.

- String attachment clamps. Palm fiber cords. Cords of the order of one meter are still available on the market in Siem Reap, but the manufacturers are old men and the bell will soon ring. We also tested a fastening with cowhide ties but the aesthetic result is less. The ancient Khmers may have used deer leather. We have also tested cotton cords, like Burmese harps, but their use in the 7th century cannot be proven. The tuning is easier. The knotting used is that of Burmese harps but difficult to handle. Because of this complexity, the instrument becomes "personal" and can hardly be passed from hand to hand.

- Acoustics. The instrument has little sound but fits perfectly into the string orchestras depicted on the two lintels of Sambor Prei Kuk. In order to amplify the sound, we have installed, at the base of the strings, bray-pins made of fine bamboo needles fixed on the bridge with wax. This sound has always been sought after in India and is the norm on some contemporary Khmer cordophones (chapei, krapeu). The bin-baja harp of the Pardhan musicians of Madhya Pradesh is equipped with a saw-tooth shaped tailpiece which fulfills this same function.

- General notes. The instrument is not very powerful. It is difficult to stretch the strings. The addition of bray-pins creates an indispensable amplification even if we cannot prove its original presence.

Angkorian harp

Representations of Angkorian harps can be found in various Khmer temples and places: Angkor Wat, Bayon, Banteay Chhmar, Banteay Samre, Eastern Mebon, Preah Pithu, Elephant Terrace. The shape of the instruments differs according to the sculptors. There is no standard, like the Karen harps of Myanmar and Thailand for which there are as many models as there are musicians. However, all harps have in common a boat-shaped soundbox and a more or less arched neck.

During the reign of King Jayavarman VII (Bayon period, late 12th - early 13th century) the harp, accompanied by other instruments, animated the palatine and religious dance in the temples. It probably disappeared after the fall of Angkor (1431-32). A few rare representations in Buddhist monasteries, until 1975, testify to its permanence in the memory of the Khmers.

Lessons from the reconstructions

- Soundbox and neck. Same remarks as above.

- Feet. The first pre-Angkorian harp was made without feet. Then we made other models with four feet and finally returned to a front leg as shown in the bas-reliefs. The Angkorian harp is played da gamba or the instrument placed on the ground, which requires, in this case, a good stability.

- Tailpiece. Same remarks as above. It is important to find the right balance for the thickness of the tailpiece: too thick, it will conduct the sound badly, too thin, it will bend and break under the effect of the tension of the strings. The structure of the wood should be perfectly homogeneous.

- Soundboard. Same remarks as above.

- Strings. Same remarks as above. Two high reliefs show that the string came to the peg from the outside and not through a hole in the neck. When tuning, one must make sure that the string is as close as possible to the neck on the peg (without touching it) so that the tailpiece remains straight. When installing the strings, it is advisable to perform successive tunings so that all the components of the instrument take their place: string tension, tailpiece and neck bend. Temperature and humidity affect the overall tuning. Therefore, it is advisable to warm up the harp before tuning it if it is to be played in a different place from where it is stored.

- Soundboard attachment. The attachment of the soundboard skin to the soundbox was done both by gluing and nailing with needles carved in bamboo like Burmese harps.

- Pegs. The pegs are made from Cambodia's most precious wood, kranhung ក្រញុង, Dalbergia cambodiana. This essence was once reserved for royalty. We believe, however, that the pegs of the most prestigious instruments were made of elephant ivory, which made it possible to reduce the diameter and, therefore, increase the precision of tuning and robustness.

- Decoration of the summit part. On the bas-reliefs, the neck usually ends abruptly with a simple cross-section. On the most prestigious instruments, the outline of a bird's head appears. We have made these various configurations.

- General aesthetics. The bas-reliefs do not give us any information about the decoration of the harps. We can only note that the Burmese harps of the 19th century were lacquered and gilded. We have therefore, for aesthetic reasons related to the taste of some sponsors, made decorations with natural lacquer or acrylic, single or multilayer, with 24 carat gold leaf.

Angkorian harp with Garuda head

From the beginning of the twelfth to the middle of the early thirteenth century (end of Angkorian iconography), the neck of some harps was surmounted by a Garuda head (Angkor Wat, Bayon, Elephant Terrace, Banteay Chhmar, Western Gate of Angkor Thom). In Hinduism, Garuda is the vehicle of Vishnu and in Buddhism, the guardian of the teachings of Buddha. The Garuda-headed harp seems to have been played for entertainment, in the presence of jesters, and to accompany singing jousts.

The lessons learned from the reconstruction of the Garuda head harp are the same as for the Angkorian harp. The addition of the Garuda head, carved in a piece of jackfruit wood, changes the stability of the instrument when it has only one front foot. In this case, the four legs are really welcome.

Lute

The piriform lute existed in India during the Gupta period. Some rare sculptures corroborate certain Siamese, Cham and Javanese representations of the Borobudur period. We present here the lintel of Pawāyā, property of the Gujari Mahal Archeological Museum. It clearly shows, at the bottom left, a lute with a piriform soundbox.

The instruments that make up this orchestra can be compared to the lists of instruments in the Lolei temple (9th century).

No lute is represented in Khmer iconography, although the pre-Angkorian term trisarī refers to it. The latter is probably a trichord lute as the prefix of the word indicates.

The instrument opposite was reconstructed by crossing several sources: Cambodian epigraphy, iconography from Champa, Siam and the temple of Borobudur in Java (Indonesia).

We made a proposal for a reconstruction because we had to move forward, even if it meant making mistakes. Many questions remain unanswered but, beyond the plastic and aesthetic details, one of them is important: did the trisarī have frets? We took the option of making a fretless monoxyle instrument with a goatskin soundboard glued and nailed with bamboo nails. The strings are made of Nylon microfibers, formerly, perhaps silk, gut or metal. The end of the neck has been provided with a scroll, like the pre-Angkorian harp and some ninth century decorations in Hariharalaya (Roluos archaeological group). The pegs are made of red wood with bone inlay, and the bridge is made of bamboo.

Conch shells

The conch is a lip-reed instrument made from a gastropod whose apex has been cut off, or its terracotta facsimile. On the bas-reliefs of Bayon and Angkor Wat, conches are mostly seen in battle scenes, commemorative or fictitious, those of the Reamker and Mahābhārata epics, as well as in Brahmanic rituals. The sculpture does not allow us to define the material.

To our knowledge, no Angkorian blowing conch made from a gastropod has come down to us, which does not mean that none existed. Indeed, at least one libation conch, made from a gastropod inlaid in a bronze frame, has been found in archaeological excavations. On the other hand, numerous examples of terracotta conches have been excavated.

At Angkor Wat and Banteay Samre, the conches are depicted with a makara mouth-shaped outlet (मकर Sk.). We do not know if this is a conventional aesthetic of the graphic representation or if the conch was truly fitted with a metal mount, in the manner of the Tibetan Buddhist ones. We had a pair of conches made by a Newar craftsman from the Kathmandu valley (Nepal) with a copper frame, edged with brass. We also reconstituted a conch in terracotta. For that, it was necessary, before the work of the ground, to manufacture the internal spiral of the gastropod. We made it out of papier-mâché. Once the material was dry, we molded the clay around it and put the object in a ceramic oven. The paper was charred and the clay baked without damage. We do not know how the ancient Khmers did it. Perhaps they used beeswax since they knew the technique of casting bronze with lost wax.

Horn

The horns of wild or domestic cattle, or olifants, are difficult to identify among the horns represented in the iconography. However, given their existence until the present time and their wide distribution in Southeast Asia, we have made such objects from water buffalo horns, the only available and legal material. However, it is certain that wild buffalo horns and elephant tusks were used, which is confirmed by ethnography.

There are two qualities of buffalo horns: light and heavy. The former are preferred because only the tip is filled with material.

After cutting the end of the horn, the manufacturer fires at least two or three irons to accelerate the process. He opens the insufflation duct millimeter by millimeter. Then the mouthpiece is rounded to facilitate the insufflation without hurting the lips. The horn is then cleaned and polished with sandpaper. In the past, the polishing may have been done with wild plant leaves, still known today by forest people. A model was made by adding a copper border with lotiform decoration.

Manufacture of a horn from buffalo horn.

Flutes

Representations of flutes are rare among the Angkorian iconography. Only two types have been represented: transverse flute (lateral mouthpiece flute) in the pre-Angkorian period, flute with terminal mouthpiece in the Angkorian period (only two images in Angkor Wat) and post-Angkorian period (16th century, third enclosure, north gallery, east wing, of Angkor Wat). We made the bamboo transverse flute with reference to Asian models.

Oboe

Until 2020, we thought that the oboe appeared for the first time in the iconography of the 16th century (bas-relief of the third enclosure, north gallery, east wing, of Angkor Wat, and painting of the central sanctuary of this same temple). However, the recent reassembly of the eastern enclosure wall of the Banteay Chhmar temple (late 12th - early 13th century) has thrown up some confusion. An oboe appears next to other martial instruments, including a drum chime that is totally absent from the other temples. Or are they not Khmer? Perhaps the Burmese (?).

To reconstruct the oboe, the maker used koki wood គគីរ (Hopea odorata) for the body, coconut for the bat-like pirouette with outstretched wings, sugar palm leaf for the quadruple reed, and rolled copper leaf to connect the reed to the body. The body is pierced with seven equally spaced playing holes.

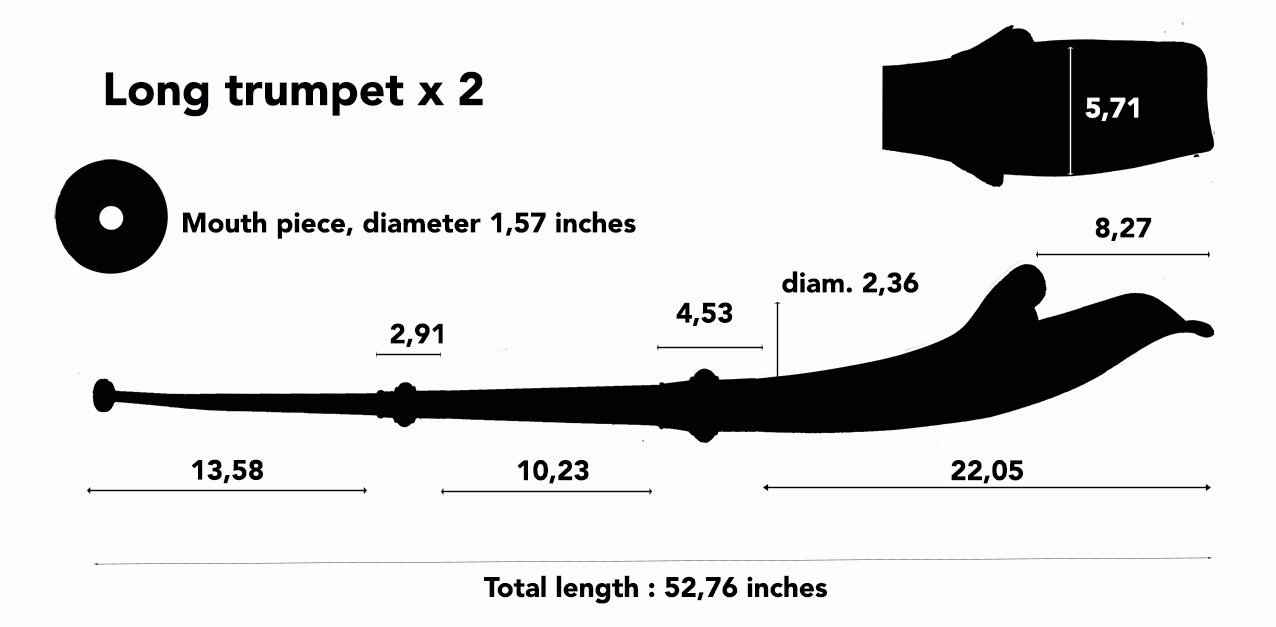

Trumpets

Trumpets are almost always present in the martial orchestras depicted at Angkor Wat, Bayon, Banteay Chhmar and some other lesser temples. It is not easy to determine the nature (horn or trumpet), the shape and the material of the instrument. Fortunately, some occurrences are more explicit.

Metallic trumpets

The bas-relief of the Great Procession of Angkor Wat (third enclosure, south gallery, west wing), shows a martial parade orchestra composed of trumpets, conches, drums and cymbals. The trumpets are undoubtedly made of metal, copper or bronze. If contemporary Khmers know how to work these metals to make boxes and jewels, the making of trumpets cannot be improvised. This is why we have exceptionally gone outside Cambodia to seek expertise.

We knew that the Tibetan Buddhists made and still make their trumpets and conches successfully by the Newars of the Kathmandu valley. We then decided to go there in order to find a manufacturer who would accept the challenge of a reconstruction of Angkorian trumpets. We provided him 1:1 scale drawings. We ordered two large telescopic trumpets in three sections with brass junction and borders, three small copper trumpets with decorative brass rings and two conches from India bought on the local market, enhanced with a copper frame bordered with brass. As the manufacturing time was several months, we returned to Cambodia. The trumpets and conches were shipped to us. The result is excellent.

Bamboo trumpet

A Bayon bas-relief (outer east gallery, south wing) shows a trumpet of enigmatic shape, made up of a juxtaposition of spheres of increasing size that does not correspond to any model recorded elsewhere. It seems to be a bamboo trunk of the species Bambusa vulgaris Wamin. As for all bamboos, it is necessary to cut the thatch at a precise time of the year and to immerse it for several months in water, otherwise the bamboo will curl up. It is also easy to choose a thatch that is naturally dried on the ground. As this kind of bamboo is not naturally hollow, it must be hollowed out, which makes the object all the more precious. This operation requires a day's work because the thatch is curved; it can only be drilled by hand because, in addition to the constraint of the curve, the drill must be conical. As the interior is porous, the ideal is to coat the interior with natural lacquer to obtain a clear sound.

Drums

The bas-reliefs of Angkor Wat (early 12th c.), Bayon and, to a lesser extent, Banteay Chhmar (late 12th - early 13th c.), are full of representations of martial orchestras showing several types of drums. We know the names of some of them from Sanskrit texts.

- Cylindrical drums (11th to 13th c.)

- Goblet drums (11th to 13th c.)

- Hourglass drum timilā (7th to 13th c.)

- Barrel drums (7th and 16th c.)

- Large shoulder carried drum. We call it this because its nature is imprecise. Indeed, it is always represented from the front, on the membrane side, which does not show its depth. If we refer to all the large drums known in Southeast Asia, their shape varies: cylinder, barrel, frame... We think that the large Angkorian war drums were either barrel drums or frame drums, depending on their use and their size. This instrument is probably of Chinese origin and is called sgar in the texts. This term appears at the end of the 10th century (inscription K. 1167), at the very beginning of the 11th c. (K. 814) and in the 14th c. (K. 754). The root of this word is found in the name of the large barrel drums of the ethnic groups of the high plateaus bordering Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam (sögör, hgör, högor...); it also forms the basis of the Khmer term skor ស្គរ which generically designates drums in modern Khmer.

Cylindrical drums

Cylindrical drums of various lengths appear on the bas-reliefs, some played with bare hands, others with a bare hand and a stick, still others with two sticks. With a few exceptions, only Sanskrit texts offer lists of drum names; however, it is impossible to reconcile these texts with the iconography with certainty. Some short drums appear to be cylindrical. However, after reconstitution, their acoustic performance is null. We have then opted for the edakka hourglass-shaped drum cited in the texts and persisting in southern India.

Goblet drums

Goblet drums have a single laced membrane. Today, they are made of wood but in the past, they were (also?) made of clay. This technology has now been abandoned because it is too fragile. On the bas-reliefs, the goblet drums never appear in their entirety because the foot of the instrument is always hidden between the thighs of the musician.

Hourglass drum

An hourglass drum, named timilā in Sanskrit texts, first appears in the 7th c. on two lintels of Sambor Prei Kuk, now in the National Museum of Cambodia; it is a component of the orchestra accompanying the Śiva dance. In this case, it is simply held under the arm. When the timilā plays in martial orchestras, it is carried on the shoulder. At Angkor Wat, it has a rigid stand representing two pentacephalic nāga showing two heads, two bodies trimmed with bells, and two tails. This instrument has disappeared in Cambodia but persists in southern India.

The hourglass drum is made of jackfruit wood, like many Khmer instruments. We used an electric lathe to make it. For the links, we ordered palm strings of twelve and fourteen meters depending on the size of the instruments. The manufacturer, who had a perfect know-how for lengths of about one meter, was not equipped to make such lengths. The result was perfect, but he said he would never do it again because his hands bled. Palm fiber is extremely rigid. The two frames on which the goat skins (imported from Nepal) are installed were manufactured from rattan like the stand. The nāga heads were made of bronze using the lost wax technique. As for the tails of the nāga, buffalo horn seemed to us the ideal material: pre-existing shape, robustness and flexibility. Leather links were most certainly used to connect the two membranes.

Barrel drums (7th c.)

The barrel drum appears for the first time in iconography in the 7th century, on the lintel of the Wat Ang Khna in Sambor Prei Kuk, now in the National Museum of Cambodia in Phnom Penh.

The instrument of Wat Ang Khna was reconstructed on the basis of the samphor drum, which is still used today in the pin peat ensemble, given the limited information provided by the bas-relief and the absence of similar representations before the middle of the 16tth entury. (Angkor Wat, third enclosure, north gallery, east wing). The reconstruction was made with jackfruit wood and cowhide for the membranes and the binding. The double drum at Banteay Srei was made with the same materials.

Barrel drum (11th c.)

On a lintel from the temple of Banteay Srei (11th c.), a drummer leads the dance of Śiva using two drums of different sizes, placed vertically, with a slight inclination. The two pitches are produced by two separate elements, whereas the technique of playing drums usually allows for at least two sounds on the same instrument.

Bronze instruments

Bronze instruments can be seen on the bas-reliefs of Khmer temples: large and small cymbals, elephant bells of closed and open, equine and bovine bells, half-vajra bells, bell trees, bells of drums. What characterizes these objects is that they were found during archaeological excavations or by chance.

Bell tree

Angkorian sculpture shows bell trees (or bell chimes) with two to five elements. These sound tools are carried by hand or suspended. Numerous bells, isolated or grouped, from archaeological excavations or fortuitous discoveries, reinforce our knowledge. This is one of the rare cases in Khmer archaeomusicology where we have both iconography and objects. Our quest consisted in identifying them and comparing them to the iconography. We had a cast made from an authentic bell, then the founder made the other four dimensions. We hung them beforehand around a palm fiber tie until we discovered two original bells hanging with a bronze chain. We then changed to make a copy. This method of suspension is also validated by Chinese and Japanese ethnography.

Necklace of bells for horses

War horses were adorned with majestic bells. Iconography and archaeology provide us with numerous testimonies. The necklaces of bells for horses were made up of spherical and/or mango-shaped bells of closed, distributed in one or two rows. At the Elephant Terrace, a combination of these two types of bells can be clearly seen on a high relief.

We have reconstructed this collar thanks to the discovery, in the antic bronze collection of the Wat Reach Bo in Siem Reap, of a mango-shaped bell, so close to the representation of the ones of the Elephant Terrace; that one would think it had fallen from the high relief! As for the spherical bell with an X-shaped opening, it belongs to the same collection, but is more common. Numerous examples have been found in excavations. For our reconstruction, we have molded the two original pieces.

Large and small cymbals

Large and small cymbals are widely depicted in the iconography and were present in all orchestras: martial, palatine, religious, entertainment and even to give rhythm to certain works requiring a coordination of the movements, like the earthwork of the temples. Some original bronze objects have come down to us. The large cymbals are mainly used for martial purposes. The small one are used in all other ensembles. Both are made of bronze (an alloy of copper, tin and/or lead). The large cymbals seem to have been made by hammering from a bronze cake. As for the small ones, they were also melted with lost wax.

In 2012, we found, in the suburbs of Phnom Penh, near the airport area, one of the last craftsmen, making bulbous gongs for roneat in a traditional way. He agreed to make, for Sounds of Angkor, cymbals by hammering from a bronze slab of similar thickness to that of the Angkorian instruments. The images opposite show the work. The circular wafers are made on site from salvaged metals. Khmer founders no longer know how to make bronze alloys.

For the small cymbals, we had a mold made in Siem Reap from an original model and had the bronze cast using the lost wax technique.

Rattle drum

Several damaru or damarin rattle drums (12th -13th century) have been found in excavations. They belong to museums or private collections. Some have been copied and, given the fact that few drum rattles have been found in official excavations, it is not easy to form a general idea of the models that actually existed. We have identified only one occurrence of this type of object among all the Angkorian bas-reliefs, and its quality of execution as well as its state of conservation are poor.

Our work therefore consisted in identifying these objects, making copies of them and, where necessary, completing the destroyed organic parts.

We have reconstructed three damaru drums from three originals whose authenticity is attested, all from photographs and measurements taken on the originals:

- frame-shaped damaru (collection of Wat Reach Bo, Siem Reap).

- hourglass-shaped damaru (same collection). It was broken in two and the two fragments had been identified independently. We brought them together and determined that it was a rattle drum.

- frame-shaped damaru (Musée Guimet - Paris). We restored the broken top parts based on similar carvings from the same period. The neck was made from a later model belonging to the National Museum in Bangkok.

Scraper

During our research, the scraper was the most difficult instrument to identify, particularly because of false information peddled in the literature. It still exists in Cambodia, although it is little used. We propose here a reconstruction that combines Khmer and Vietnamese influences. This scraper-clapper consists of two articulated boards, one smooth, the other grooved, and a stick to scrape the grooves. Nothing in the bas-reliefs attests to this typology, but until recently, there were clappers used to mark the steps of dancers. We have added, as in Vietnam, two groups of pierced Chinese coins which bring a metallic sound when the two planks are clashed.

Orchestral reconstructions

Once the instruments were reconstructed, we wanted to test their acoustic coherence. This is a fundamental step in experimental archaeomusicology. For this purpose, we created the Sounds of Angkor band, taught the instruments to play and took options for a musical repertoire. For the music of the string orchestras, we involved the Department of Music of the Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts of Cambodia, which made a choice among the oldest musical pieces.

Pre-Angkorian string orchestra (Sambor Prei Kuk, 7th century)

The orchestra shown below represents a dance of Śiva. The lintel comes from Sambor Prei Kuk. It can be seen at the National Museum of Cambodia in Phnom Penh.

Sounds of Angkor brought together here: a singer, a single-stringed zither with a calabash resonator, an arched harp, small cymbals and a barrel drum (which also existed at that time.

Orchestra accompanying the sacred fire. Angkor Wat, third enclosure, south gallery, west wing

The orchestra accompanying the sacred fire (Angkor Wat, third enclosure, south gallery, west wing) is, in many respects, the most prestigious both in its graphic representation and in the quality of reconstruction of instrumental details. This (reconstructed) ensemble was notably used to welcome His Majesty King Norodom Sihamoni in June 2014 at Angkor Wat. We were privileged to be able to ring it around the central shrine in the presence of many spectators and the international press.

From R to L. foreground: two dancers (initially five), large shoulder carried drum, small cylindrical drum struck with two sticks, hourglass drum.

From right to left, background: cymbals (invisible but the player is clearly present between the small trumpet player seen from the front and the front drum bearer), pair of small trumpets, pair of conches, pair of large trumpets with makara mouth. Angkor Wat, third enclosure, south gallery, west wing. Historical parade. 12th c.

The two sequences below present, on the one hand, this orchestra played by the Sounds of Angkor troupe and, on the other hand, its staging in a 3D realization of Monash University (Sydney, Australia) realized with the collaboration of Sounds of Angkor for the sound.

Impact of Sounds of Angkor on Cambodian instrument making

This project has allowed several Cambodian craftsmen to develop new skills around traditional materials: wood for instrument making, precious wood, horn, bone, leather, rattan, various vegetable fibers, lacquer, gold leaf, casted and hammered bronze...

The craftsmen, Cambodian and French, are located in various provinces of Cambodia: Ratanakiri, Phnom Penh, Kandal, Siem Reap. Since the beginning of the project, we have solicited about twenty workshops and individual artisans.

Development of a Franco-Khmer Pole of Excellence

In 2019, we created a Pole of Excellence combining the know-how of Cambodian and French artisans based in Cambodia. The workshops under French management already ensured the transfer of know-how to Cambodian craftsmen, particularly in the field of lacquer (natural and acrylic) and gold leafing. The objective was to produce professional instruments combining acoustic and aesthetic qualities, while allowing craftsmen of various disciplines to perfect their skills.