Last update: December 5, 2023

Discovery of the first harp

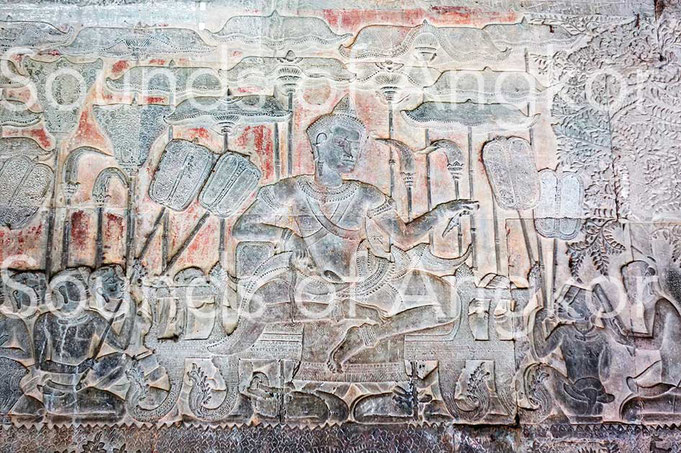

We are currently (2023) in possession of over forty representations of Khmer harps, including those from the pre-Angkorian and Angkorian periods. The most numerous come from Bayon, Banteay Chhmar and the Terrace of the Elephants. However, Angkor Wat remained the big absentee when it came to depictions of harps. But one fine day in 2017, a harp finally appeared in the sights of our research after nineteen years of hoping. This representation constitutes the missing link between the rare 7th-century representations of Sambor Prei Kuk, the instrument lists of the 9th-century Roluos group and the temples of the Bayon period, late 12th - early 13th centuries. For the first time, a harp associated with a zither is discovered at Angkor Wat.

In the initial iconography from the early 12th century at Angkor Wat, we knew about martial orchestras and a few rare sound tools used by Brahmins. But why has it taken us so long to discover this image? Because it lies between two poles of great iconographic interest. This led me, on each visit, to move from one pole to the other, forgetting to inspect this "minor" ensemble. This modest string orchestra therefore appears on the pedestal of a doorway. Even if the whole of the pedestal scene is interesting in many respects, we'll cut to the chase here, describing the instruments, musicians and actors involved.

The scene is unfinished but, miraculously, a number of black lines remain from the 12th c. onwards. On the other hand, two medallions to the right of the scene remain blank; only a few black pencil lines remain, awaiting the sculptor's return...

Shiva's Dance

The scene depicts a Shiva's dance animated by three instruments: a double-resonator zither, an arched harp and a pair of small cymbals. Each musician is represented in an independent medallion, but all are linked by the theme of the scene.

There are numerous representations of the Dance of Shiva in Cambodia between the 7th and 13th centuries. All are different and typically Khmer in their interpretation and decorum. Here, Shiva is depicted in the central medallion. He can be recognized by his ten-armed dancing stance and the overall situation. His five right arms are clearly visible. His left arms, on the other hand, form an imprecise, unfinished mass. Incidentally, many of the "Dance of Shiva" figures on the Angkor Wat pedestals are unfinished, particularly Shiva himself, and even more precisely, his five left arms. We don't know why, but it could be linked to a belief (superstition) about death. Elements of decoration from King Suryavarman II, but also Jayavarman VII, are also unfinished. A horizontal piece of cloth, behind the leg on the floor, testifies to the dynamics of his dance.

Apsaras

Above Shiva, five highly stylized apsaras hold lotus flowers. Their legs are not represented. See our article Apsaras or sacred dancers?

Kāraikkāl Ammaiyār

In the register below Shiva, on the far left, this wiggling figure is none other than Kāraikkāl Ammaiyār, a devotee of the god. For more information on this character, click here.

Vishnu

Next to Kāraikkāl Ammaiyār stands the god Vishnu. Two of his attributes can be seen: the disc in his upper right hand and the conch shell in his left. In his two lower hands, he holds a zither. We can clearly see the curved lower part of the instrument, where the string and the circular resonator, usually made of a calabash, are attached.

Ganesha

On the far right, Ganesha, Shiva's elephant-headed son. His eye is drawn in black. He wears a conical crown. His arms are adorned with prominent bracelets. His garments lie on the ground. His hands, whose engraving is unfinished, seem to be placed one above the other, but there is no indication that he is playing any kind of instrument. Perhaps he's simply clapping.

Brahma and King Suryavarman II

Next to Ganesha, a medallion contains two figures. On the left, the god Brahma, recognizable by his four heads. Three of them are visible. The engraving of the three visible faces is not complete, but the outline of the faces remains. The god plays cymbals. The sculptor didn't carve them either, but the initial black pencil outline is still present. We have been able to isolate these strokes and make them appear in violet.

Next to Brahma, a figure with human features wears a conical headdress typical of the royal court of Suryavarman II. It appears to be the king himself, for several reasons:

- He wears the royal crown (even if the princes of the court wear the same)

- He wears a clearly visible armband on his right arm

- The initial drawing shows that he's wearing a harness

- He is seated in the same position as Brahma.

Who else could be so close to Brahma the Creator, if not this megalomaniac king? He sits at the same level as the god, whose head is slightly tilted towards the King, the Chosen One. The King is even taller than Brahma, which is no mean feat! The seating position of both figures is similar, which is important in Khmer symbolism. Suryavarman II looks the deity in the eye, as equals. The two figures brush against each other. The god seems to offer the king a lotus flower, the same symbol that the sovereign holds in his left hand on his throne. This scene takes on a whole new dimension, as the king is Brahma's envoy on Earth. Brahma as creator of the Universe, and Suryavarman II as its "re-creator" in the immensity of the Angkor Wat masterpiece. How then can we fail to see, beyond the conformist interpretation of the five central towers as representing Mount Meru, the sum total of the nine towers (5+4) of the central architectural mass and see through them the nine planets with, at the center, the Sun. On his death, King Suryavarman (Surya = Sun) may well have planned to be placed at the center of the universe!

The harpist and his harp

Below Shiva, a harpist is depicted in human guise. He wears the conical headdress of royalty. He could therefore be a man of the high Angkor royal hierarchy and not a simple craftsman-musician, and why not, once again, King Suryavarman II himself as the animator of the Universe! He is depicted centrally, just below Shiva, master of music and dance. The musician's position differs from the usual representations; his left foot is lower than the base of the instrument, which could mean that he is not seated on the ground, but on a table-bed (in this case a lotus), let's say in the manner of the king on his throne! This idea is reinforced by the slightly higher position of the right foot.

The practice of music is considered a sign of good education and finesse of mind; we know this from the praises of Khmer iconography written in Sanskrit.

An inscription (K. 573 to 575) from Banteay Srei, 10th c., reveals:

"Eminent in beauty, power, glory, science, virtue, deeds, spiritual merit, he had no pride. He knew music; he had studied the arts: mechanics, astronomy, medicine, etc..."

Or this royal eulogy from the stele of Sdŏk Kăk Thoṃ, mid-11th c.:

"Experienced, learned, wealthy, renowned for his kindness to all and for his musical talent, he ceaselessly delighted the hearts of courtiers with the five bonds that courtesy engenders."

"He was the first in the knowledge of the doctrines of Patañjali, Kaṇāda, Akṣapāda, Kapila , the Buddha, in that of medicine, music and astronomy."

We don't know how many strings harps were equipped with in the Angkor Wat period (early 12th c.). In the Bayon era (late 12th - early 13th c.), the best iconography shows that the number reached 21. In Vedic literature, 21 is associated with both the Earth and the Sun.With 21 intervals (syllables), man reaches the Sun, for this star is the twenty-first from our world. Now, we've discovered that the central tower of Angkor Wat represents the Sun, and that King Suryavarman II's post-mortem project was (perhaps) to have his remains (remains or ashes?) deposited at the center of this symbolic sun. Angkor Wat is probably the mausoleum of King Suryavarman II.

In Vedic literature, which this king probably drank from, there's another notion, linked to the 22 notes (śrutis) of the early Indian musical system.

This number represents a point beyond the Earth or the Sun.With it, Man conquers that which lies beyond the Sun, i.e. glory and liberation from sadness.

We don't believe that Angkorian music was modelled on the Indian musical system, but Indian philosophy has sufficiently influenced the world of architecture and the arts, particularly global theater (dance, music, song, etc.), for this very idea to find a place here.The harp, a fixed-note instrument, cannot a priori play all 22 śrutis, but only the 7 notes of the scale.Admittedly, this instrument existed at the time the śrutis theory was laid down.

Only tube or stick zithers, with their high frets, would have been able to play all 22 śrutis. This is probably one of the reasons why the harp disappeared from India from the 10th century onwards; it was replaced by instruments (lutes, zithers, to mention only the strings) capable of following all the micro-intervals produced by the voice. In ancient times, the harp was only used to accompany the voice, not to play complex melodies.

The importance of mastering the arts

The magnificence and perfection of Angkor Wat can only be understood by delving into the ancient texts of India. The Vishnudharmottara Purana provides an insight into the origins of image creation and the interdependence of the arts. The wise Markandeya instructs King Vajra in the art of sculpture; he teaches him that to attain it, one must first learn painting, dance and music :

“Vajra: How must I create the forms of gods so that the image can always manifest divinity?

Markandeya: He who does not know the canon of painting (citrasutram) can never know that of image creation (pratima lakshanam).

Vajra: Explain to me the canon of painting, for he who knows the canon of painting knows that of image-making.

Markandeya: It's very difficult to know the canon of painting without the canon of dance (nritta shastra), because in both the world must be represented.

Vajra: Explain to me the canon of dance and then you'll talk about the canon of painting, for he who knows the practice of the canon of dance knows painting.

Markandeya: Dance is difficult to understand for someone who doesn't know instrumental music (atodya).

Vajra: Talk about instrumental music and then you'll talk about the dance canon, because when instrumental music is well understood, dance is understood.

Markandeya: The dance is difficult to understand for someone who doesn't know instrumental music (atodya).

Vajra:Talk about instrumental music and then you'll talk about the canon of dance, because when instrumental music is well understood, one understands dance.

Markandeya: Without vocal music (gita), it's not possible to know instrumental music.

Vajra: Explain to me the canon of vocal music, for he who knows the canon of vocal music is the best of men who knows everything.

Markandeya: Vocal music must be understood as subject to recitation, which can be done in two ways, prose (gadya) and verse (padya).”

We can therefore accept that the image of the harp player could be that of King Suryavarman II, and perhaps also understand that no other harp or stringed instrument, in the context of a Dance of Shiva, is represented elsewhere in Angkor Wat. Admittedly, another harp (shown below) is indeed depicted, but in a completely different context, which probably escaped the foremen's vigilance as the related images seem to have gone astray (but this is only our opinion).

Special features of King Suryavarman II's harp

The contours of the boat-shaped soundbox are typical of Angkorian harps. The instrument's stabilizing foot is clearly visible at the front of the soundbox, as on harps from the Bayon period. This simple detail proves that the sculptor was perfectly familiar with the structure of the instrument, unlike the sculptors of the other pedestals who simply depicted the string players in playing position, but not the instruments themselves.

The top of the neck appears to be surmounted by a bird's head. Such representations are still common today among the Karen of Myanmar and Thailand. The strings and neck attachment were sketched by the artist in black pencil and preserved to this day. This bird's head cannot be mistaken for a Garuda head, even if it is merely suggested. Looking at the environment of the second harp found at Angkor (shown below), it seems impossible that there could be any confusion of genres. Admittedly, the Angkor Wat period is different from that of the Bayon, but as far as we know, Garuda-headed harps were reserved for entertainment or ritual purposes involving jesters.

Karen bird-head harps

The Karen live in Myanmar and Thailand. They play bird-head harps. You can see and hear them in our film "Mysteries of the Khmer harp" (Timecode 5:09).

The dancing Shiva scene at Preah Pithu

To take our analysis of the Angkor Wat harp further, let's compare it with the Dance of Shiva from the Sanctuary U of Preah Pithu temple.

The general construction of the scene and the characters present similarities: Shiva, in the upper register, stands on his right foot; his ten arms remain in the same position. At the foot of the god, on the left, Brahma, and on the right, Vishnu. Brahma holds a closed lotus flower in his upper right hand. His left hand is invisible. His two lower hands are joined one above the other, while Vishnu's are disjointed. The fingers of Brahma's left hand are slightly bent, while those of Vishnu are extended. One of them may be playing cymbals, but they are not represented. In the lower register, Ganesha's hands are in the same position as Brahma's, but with right and left hands reversed. None of the three figures is in a position to play a zither or a scraper. Perhaps they are clapping?

In conclusion

What new information does this representation provide?

It confirms the existence of harps and string orchestras in the first half of the 12th century. This does not represent a major discovery, since they existed both before and after Angkor Wat, but rather a scientific confirmation.

It suggests the first break in neck shape compared with 7th-century instruments. This shape would be retained until the 13th century.

The clear absence of stringed music ensembles at Angkor Wat raises questions. We know from the epigraphy of the Roluos group temples in the 9th century that music was played by women in the temples. Similarly, the iconography of several 12th-13th century temples (Bayon, Banteay Chhmar, Banteay Samrè in particular) shows both male and female string players. So where are they hiding? We propose an approach to this question in the section "String orchestras at Angkor Wat" (under work).

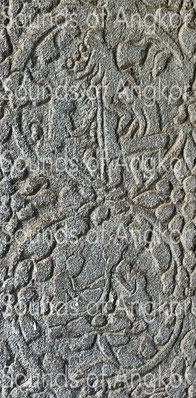

Discovery of a second harp at Angkor Wat

We were so delighted by this first discovery that we never imagined we'd find a second harp in Angkor Wat! But our persistence, after so many years pacing the temple galleries, was rewarded on May 15, 2020. While the whole world was confined by the COVID-19 pandemic, Cambodia's inhabitants were free to go about their business, since the plague had been brought under control. Moreover, foreign tourists had deserted the country, leaving an incredible silence over Angkor's archaeological park, which was conducive to our research... It is against this backdrop that a second harp has now been revealed, also from a door jamb. However, we would like to pay tribute to our French friend Œil-de-Garuda (Garuda's Eye), who accompanied us that day and whose piercing eyesight is no stranger to this discovery.

His eye was first drawn to the strangeness of a scene above the harp: figures engaged in a game of juggling and balancing, the ins and outs of which we don't yet understand.We can, however, retain the idea of a game known in Angkorian times. (We welcome any information you may have to help us decipher this scene. Trimming and coloring are given here on a provisional basis, as not all elements of the scene are included). Other adjacent medallions involving monkeys "playing" are linked to this scene, but they are so obscure as to their content that we will limit our publication to the latter.

The Garuda-head harp

The neck of the harp shown in this medallion is surmounted by a Garuda head. Until now, this type of instrument was only known from the Bayon period during the reign of the Triad (king Jayavarman VII, queens Jayarajadevi and Indradevi), i.e. late 12th - early 13th centuries. For full details of the Garuda-headed harp, click here. As a result, we can now put back the appearance of this type of harp by around a century. Not surprising, given that Angkor Wat is dedicated to Vishnu and that Garuda is the god's vehicle.

The sculpture, however, provides no reliable information on the instrument's technology. What is important, however, is the probable relationship between the harp scene and the one above it. We have recently shown that, during the Bayon period, playing the Garuda-headed harp was associated with secular artistic representations (the Bayon Circus scene in particular) and with performances featuring jesters. However, this was already the case a century earlier.

In front of the harp stands a reclining figure, one knee on the ground and hands clasped. Between him and the harp is an unidentifiable object. Perhaps this figure is part of the scene above. It is reminiscent of the sampeah kru ceremony performed by Khmer artists before each performance.